|

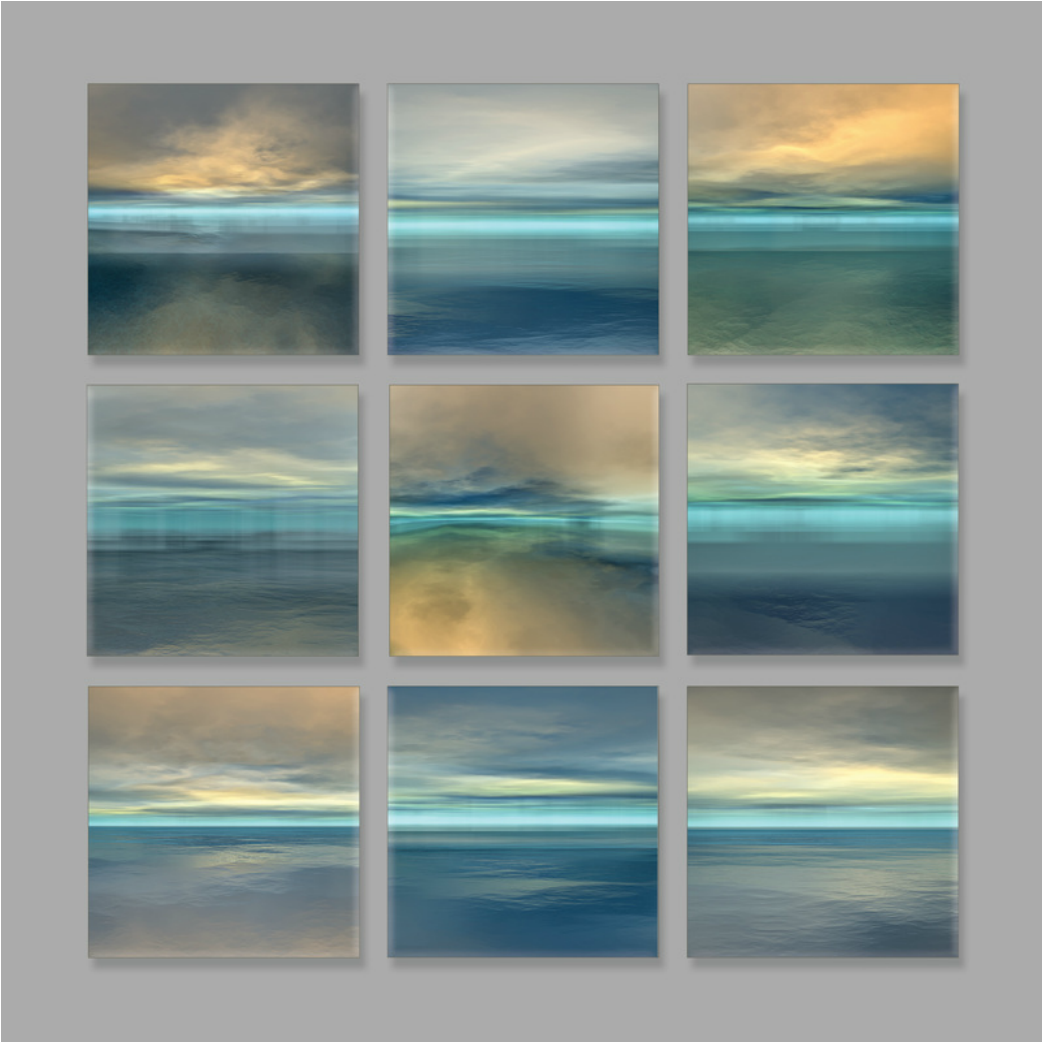

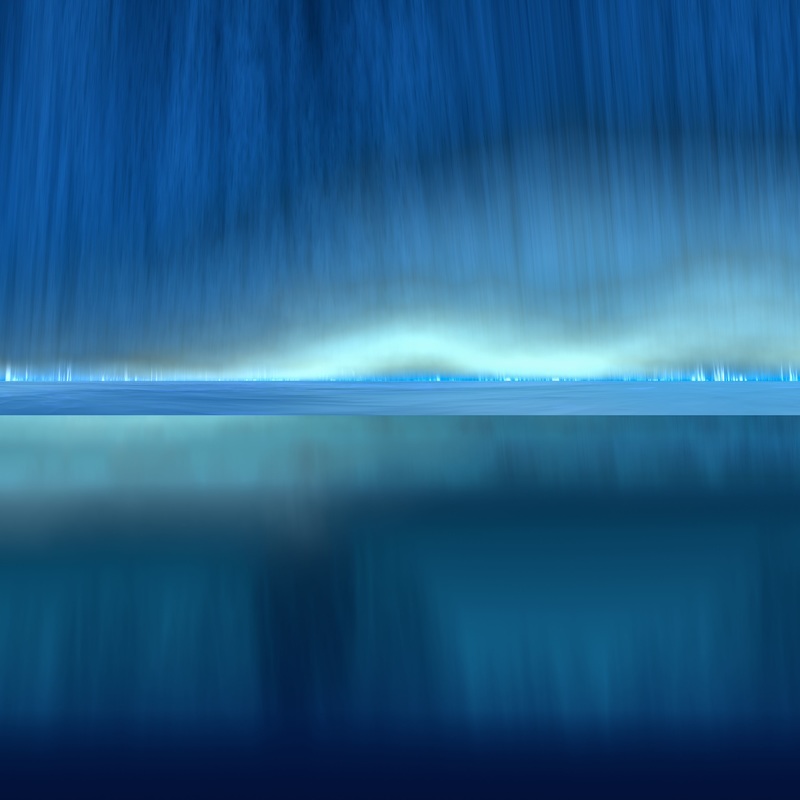

Turquoise Renaissance further develops themes explored by Paul-Emile Rioux in his earlier series Turquoise Default. It is not merely a progression however, but also a contrast. The default refers to the non-choice, in that sense it is fatalistic. This new series examines the other side, it poses questions about hope, which is perhaps now more relevant than ever. It does not simply ask how to have hope, but what it is, what it should be and what it should not be.

|

|

Text: Neal Rockwell, 2016

|

Defining hope is not simple, as it can be framed in many ways, but I will attempt a description which positions it with its greatest potential for transformation. From this perspective, it is neither optimism, nor is it pessimism. These are both fatalisms, believing either that things will turn out well or badly, regardless of our actions. In that way they both undermine individual agency. Hope begins with uncertainty, both insofar as, if we had certainty we wouldn’t need it, and secondly in the freedom for change which uncertainty affords us.

As Rebecca Solnit writes in the Introduction to the 2015 edition of Hope in the Dark:

“hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty there is room to act.”

That is to say that hope is uncertainty given agency by the power to act. Another thing which hope is not, is realism. Realism seeks to banish doubt by creating and image of what is, often quite dark, and simply acting within that perceived framework. In this way it’s a kind of disguised pessimism. The third ingredient to hope, that is to say hope which is liberating, is critical thinking. To quote again from Solnit:

“critical thinking without hope is cynicism, but hope without critical thinking is naïveté.”

Hope, however, is a kind of faith and as such it is never far from illusion. In fact, it is its inherent uncertainty, it’s containing a kind of infinity, an unfathomability, it’s dependence upon projection and image that condemns hope to an uncomfortably close and inextricable relationship with fantasy, one which no realism or platitudinous certainty can ever disentangle. Hope is a kind of power, but not one which is uniformly moral in its projection. It can just as easily disenfranchise as liberate depending on how we choose to frame it.

As Rebecca Solnit writes in the Introduction to the 2015 edition of Hope in the Dark:

“hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty there is room to act.”

That is to say that hope is uncertainty given agency by the power to act. Another thing which hope is not, is realism. Realism seeks to banish doubt by creating and image of what is, often quite dark, and simply acting within that perceived framework. In this way it’s a kind of disguised pessimism. The third ingredient to hope, that is to say hope which is liberating, is critical thinking. To quote again from Solnit:

“critical thinking without hope is cynicism, but hope without critical thinking is naïveté.”

Hope, however, is a kind of faith and as such it is never far from illusion. In fact, it is its inherent uncertainty, it’s containing a kind of infinity, an unfathomability, it’s dependence upon projection and image that condemns hope to an uncomfortably close and inextricable relationship with fantasy, one which no realism or platitudinous certainty can ever disentangle. Hope is a kind of power, but not one which is uniformly moral in its projection. It can just as easily disenfranchise as liberate depending on how we choose to frame it.

Rioux’s new series invokes the Renaissance as a kind of shorthand for reason,

possibility and the fashioning of a better world through exploration and critical self examination, that is by the Cartesian process of knowing by doubting. Formally it is similar to its sister series Turquoise Default, in that the picture plane is divided into three segments, creating a kind of double horizon in the center of the image. Unlike the earlier series, however, Renaissance has no hard lines, each section blends into another.

As Erwin Panofsky wrote, in Renaissance art “the vanishing point [or horizon line] is… the concrete symbol for the discovery of the infinite itself.” In this sense it is the limit that abolishes limits. While technically abstract, Turquoise Renaissance invokes seascapes, weather patterns, storms and calm.

Rioux intentionally works on the pivot point between abstraction and representation.

It is an immanent quality of abstraction, not that one sees what one wants to see, but that one must see something and by something, I mean a meaningful something and not simply a mass of shape and color. The human brain is incapable of simply seeing a mass of shape and color. This is the danger of abstraction, like hope, that if we approach it uncritically we think it is telling us things about the way the world is – unexamined truths – rather than what it is actually doing, which is posing questions to us about who we really are and where we might be able to go.

That is to say, in the uncritical moment uncertainties about ourselves are transformed falsely into certainties about the external world. Many people when talking to Rioux mistake his images for photographs. They sometimes go so far as to say “I know where this is,” despite the works presenting an abstract- digital look, and not containing a single real element of any kind: no buildings, no people, no landscape, no sea....

possibility and the fashioning of a better world through exploration and critical self examination, that is by the Cartesian process of knowing by doubting. Formally it is similar to its sister series Turquoise Default, in that the picture plane is divided into three segments, creating a kind of double horizon in the center of the image. Unlike the earlier series, however, Renaissance has no hard lines, each section blends into another.

As Erwin Panofsky wrote, in Renaissance art “the vanishing point [or horizon line] is… the concrete symbol for the discovery of the infinite itself.” In this sense it is the limit that abolishes limits. While technically abstract, Turquoise Renaissance invokes seascapes, weather patterns, storms and calm.

Rioux intentionally works on the pivot point between abstraction and representation.

It is an immanent quality of abstraction, not that one sees what one wants to see, but that one must see something and by something, I mean a meaningful something and not simply a mass of shape and color. The human brain is incapable of simply seeing a mass of shape and color. This is the danger of abstraction, like hope, that if we approach it uncritically we think it is telling us things about the way the world is – unexamined truths – rather than what it is actually doing, which is posing questions to us about who we really are and where we might be able to go.

That is to say, in the uncritical moment uncertainties about ourselves are transformed falsely into certainties about the external world. Many people when talking to Rioux mistake his images for photographs. They sometimes go so far as to say “I know where this is,” despite the works presenting an abstract- digital look, and not containing a single real element of any kind: no buildings, no people, no landscape, no sea....

Hope’s true meaning, of course, is contingent on what people believe. We could look into the etymological roots of the word itself which points up its original religious implications suggesting confidence in the future with God or Christ as the basis. At first glance this may seem to suggest the later definition: a more passive one in which people relinquish their agency towards some higher power. But upon closer inspection, it is not as clear as all that. It speaks, in a sense, to a theological debate such as the one that runs through the Brothers Karamzov, outlined on the one hand by the Grand Inquisitor passage, in which people are simply supposed to accept doctrine and wait, and the other form, expressed by Aloysha, in which salvation is an ongoing process, made possible through our memory of good acts, and a faith in the belief that our actions are meaningful against the often overwhelming appearance that they are not.

Which version we follow, of course, is entirely up to us. As Aleksandre Solzhenitsyn liked to remind people “the line separating good and evil passes… through every human heart.” This conflict highlights a sort of spiritual battle very much alive in contemporary America, and to some extent the rest of the world.

Turquoise Renaissance invokes in us a sense of uncertainty and a self-awareness of our limits,

of an infinity made apparent by the horizon line, the vanishing point, the moment in any spatial or temporal projection beyond which we can no longer see, but from which, nonetheless, we know the universe carries on.

At the same time it poses a choice to us: do we accept the openness of abstraction or do we insist on imposing a (false) certainty of representation in what we see in these images.

Hope is a faith made possible by uncertainty and the unknown, by an understanding that history and the future are creative acts, works of art in which we all participate.

Text:

Neal Rockwell ( 2016 )

www.nealrockwell.com

www.nealrockwellphoto.com/index

Which version we follow, of course, is entirely up to us. As Aleksandre Solzhenitsyn liked to remind people “the line separating good and evil passes… through every human heart.” This conflict highlights a sort of spiritual battle very much alive in contemporary America, and to some extent the rest of the world.

Turquoise Renaissance invokes in us a sense of uncertainty and a self-awareness of our limits,

of an infinity made apparent by the horizon line, the vanishing point, the moment in any spatial or temporal projection beyond which we can no longer see, but from which, nonetheless, we know the universe carries on.

At the same time it poses a choice to us: do we accept the openness of abstraction or do we insist on imposing a (false) certainty of representation in what we see in these images.

Hope is a faith made possible by uncertainty and the unknown, by an understanding that history and the future are creative acts, works of art in which we all participate.

Text:

Neal Rockwell ( 2016 )

www.nealrockwell.com

www.nealrockwellphoto.com/index

Broadly speaking, the Renaissance unfolded during the 15th century (quattrocento) and 16th century (cinquecento). The Early Renaissance (c.1400-1490) was followed by the High Renaissance (c.1490-1530), which in turn was succeeded by Mannerism (c.1530-1600). Although painting techniques improved immeasurably during the Renaissance, the Renaissance palette mirrored that of the Medieval Age but for three pigments: Naples yellow, smalt and carmine lake (cochineal). Other reds were vermilion and madder lake, which brought to Europe by crusaders in the 12th century.The Renaissance color palette also featured realgar and among the blues azurite, ultramarine and indigo. The greens were verdigris, green earth and malachite; the yellows were Naples yellow, orpiment, and lead-tin yellow. Renaissance browns were obtained from umber. Whites were lead white, gypsum and lime white, and blacks were carbon black and bone black.