Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

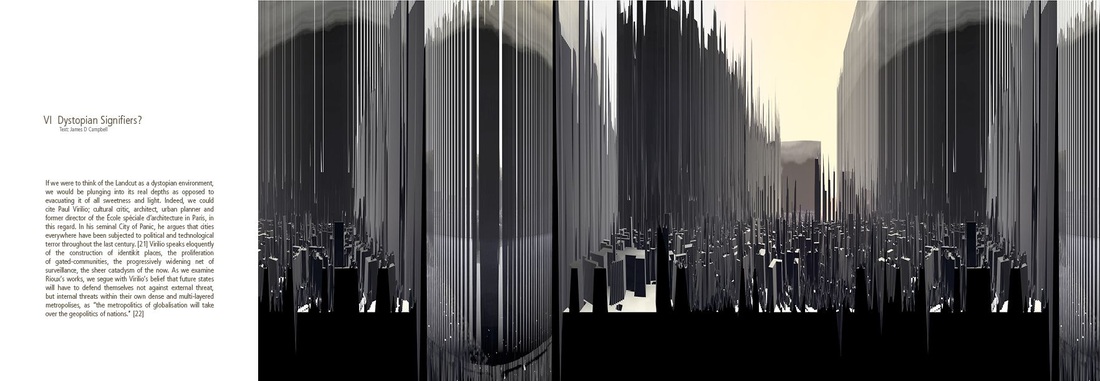

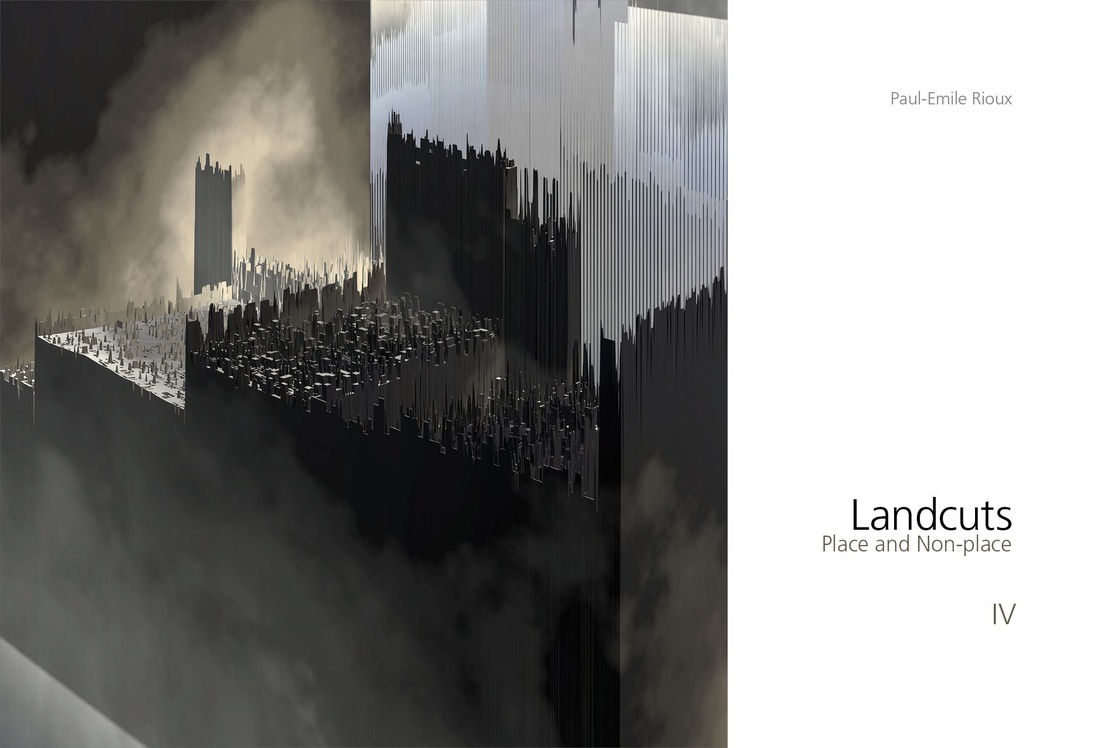

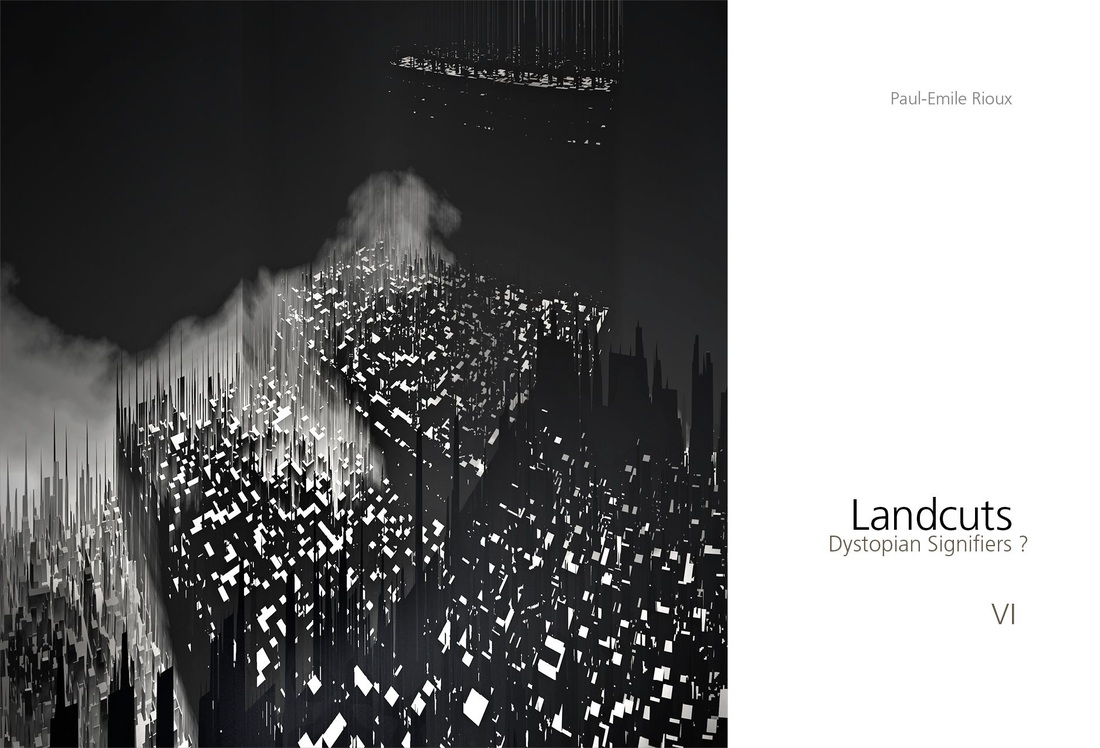

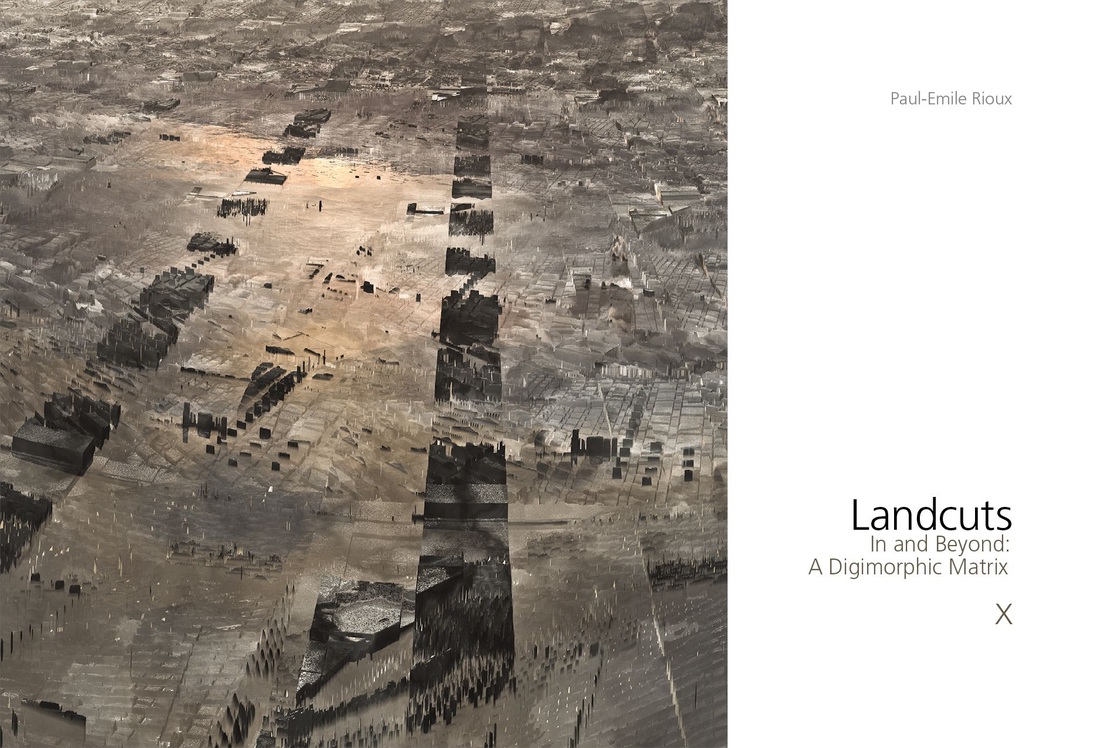

If we were to think of the Landcut as a dystopian environment, we would be plunging into its real depths as opposed to evacuating it of all sweetness and light. Indeed, we could cite Paul Virilio—cultural critic, architect, urban planner and former director of the École spéciale d’architecture in Paris—in this regard. In his seminal City of Panic, he argues that cities everywhere have been subjected to political and technological terror throughout the last century. Virilio speaks eloquently of the construction of identikit places, the proliferation of gated-communities, the progressively widening net of surveillance, the sheer cataclysm of the now. As we examine Rioux’s works, we segue with Virilio’s belief that future states will have to defend themselves not against external threat, but internal threats within their own dense and multi-layered metropolises, as "the metropolitics of globalisation will take over the geopolitics of nations."

|

If we were to think of the Landcut as a dystopian environment, we would be plunging into its real depths as opposed to evacuating it of all sweetness and light

|

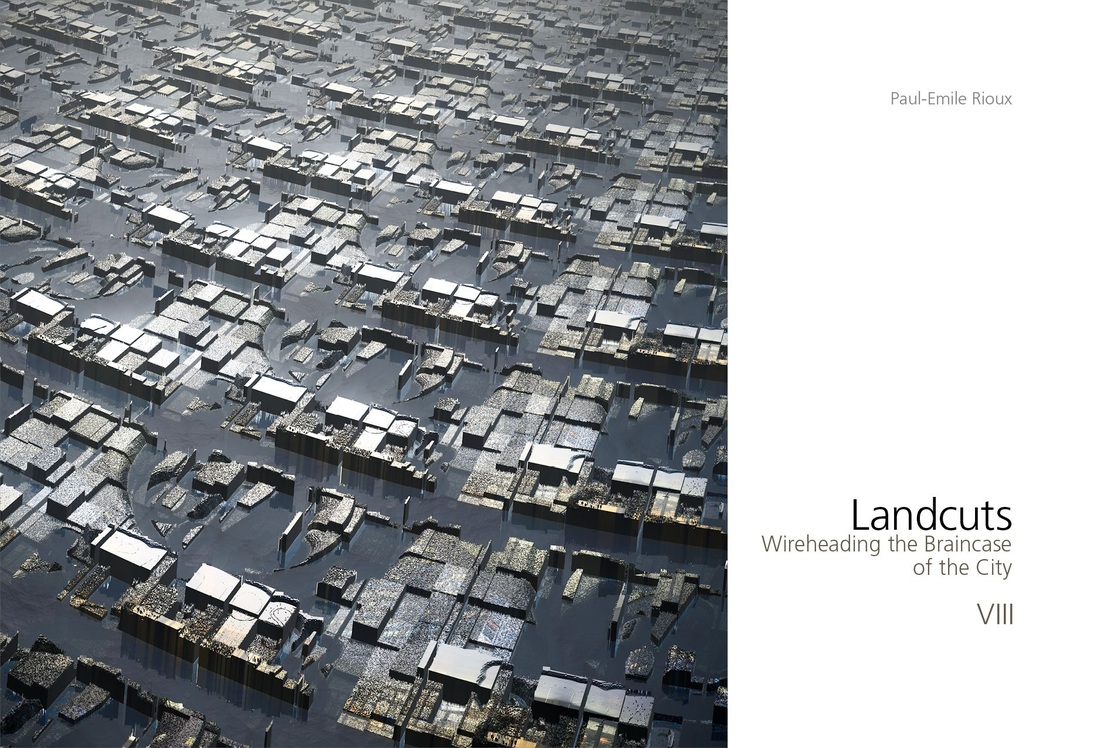

Virilio invented the name of Overexposed City for a radically excessive and in-your-face downtown core which is being perennially made over by a plethora of electronic screens. Similarly, the mien of Rioux’s prolific structures is being constantly deconstructed and reconstructed according to software that mirrors the impact of information technologies. According to Virilio, these technologies have altered our innate perception of time, which has been transformed by external stimuli. Chronological and historical time has been supplanted by the real time of the computer and plasma screen, wherein everything appears instantaneously. Real time annuls any sense of physical distance, as the faster we move around the world the smaller it seems. Consider Downtown No. 1, in which the tiered sentinels seem to be multiplying like binary code across the surface on infinity.

In Virilio’s Overexposed City, the disappearance of real space runs perpendicular to the disappearance of local or historical time. In Rioux’s phantasmal cityscapes, the "urbanisation of real space" gives way to "urbanisation in real time," a new form of creating a city based on computing and television logic. |

|

Virilio invented the name of Overexposed City for a radically excessive and in-your-face downtown core which is being perennially made over by a plethora of electronic screens.

|

|

Rioux’s phantasmal cityscapes, the "urbanisation of real space" gives way to "urbanisation in real time," a new form of creating a city based on computing and television logic.

|

|

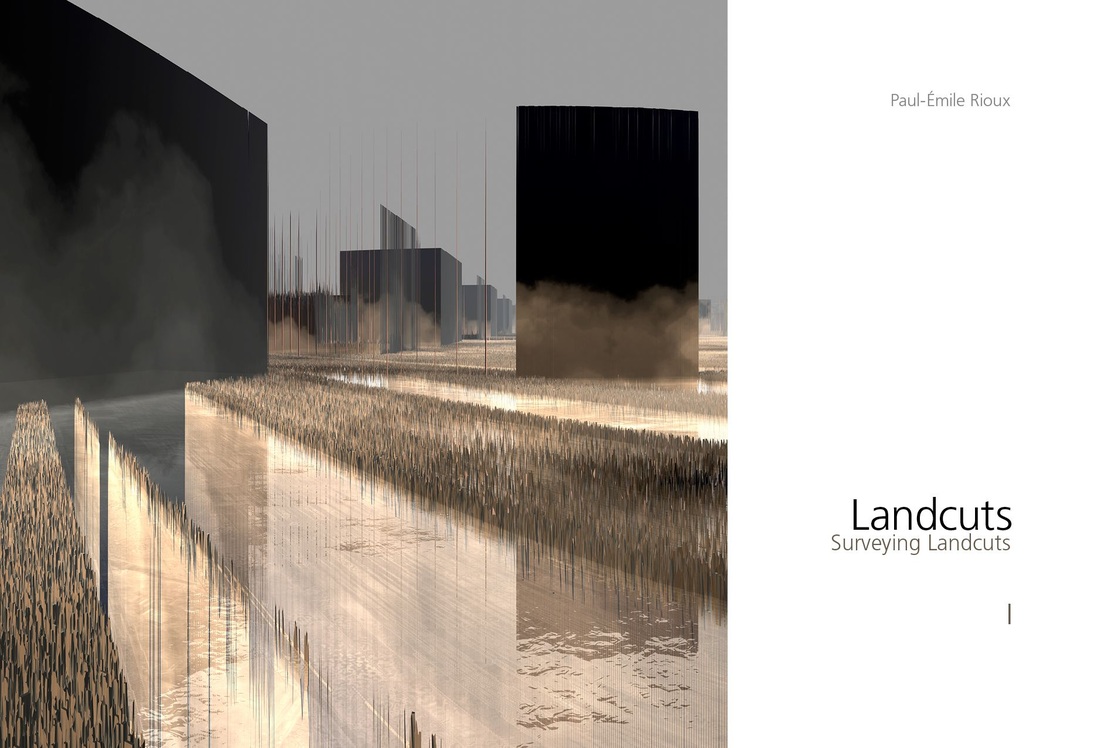

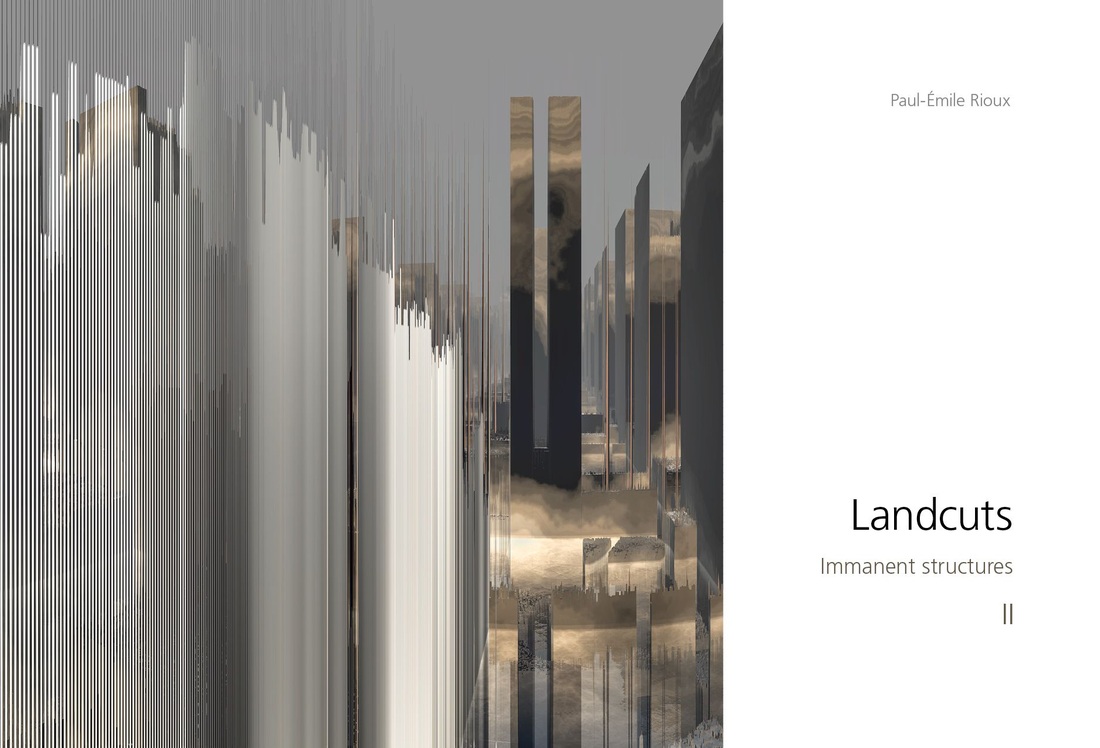

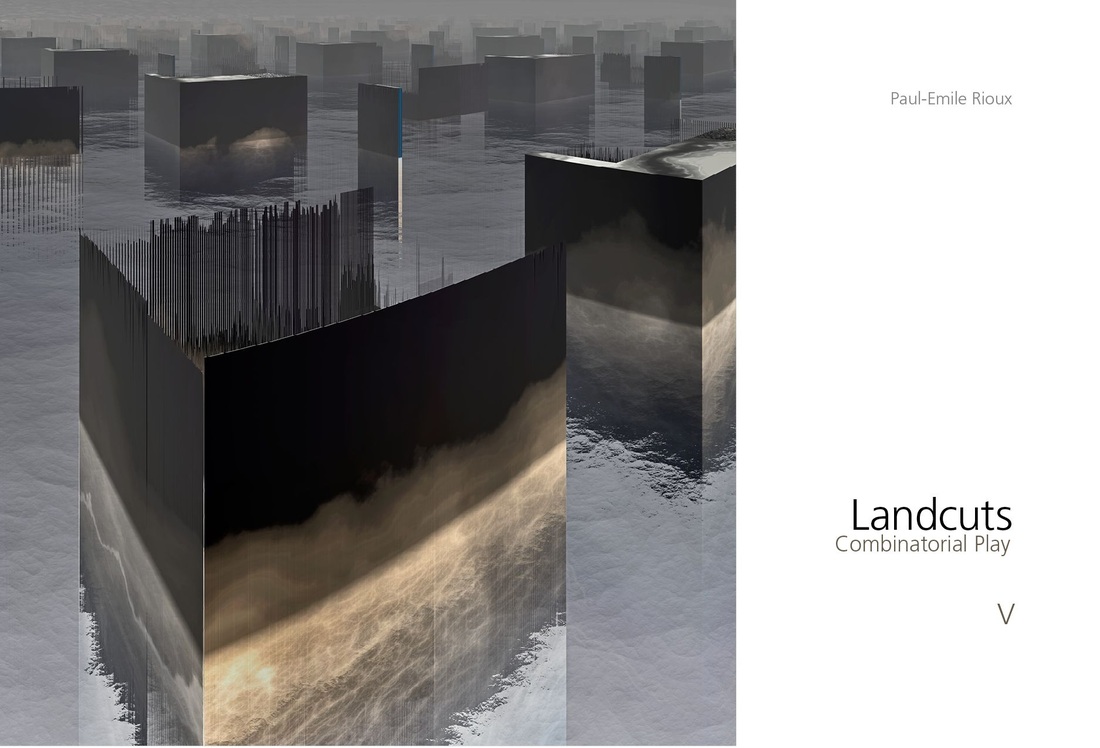

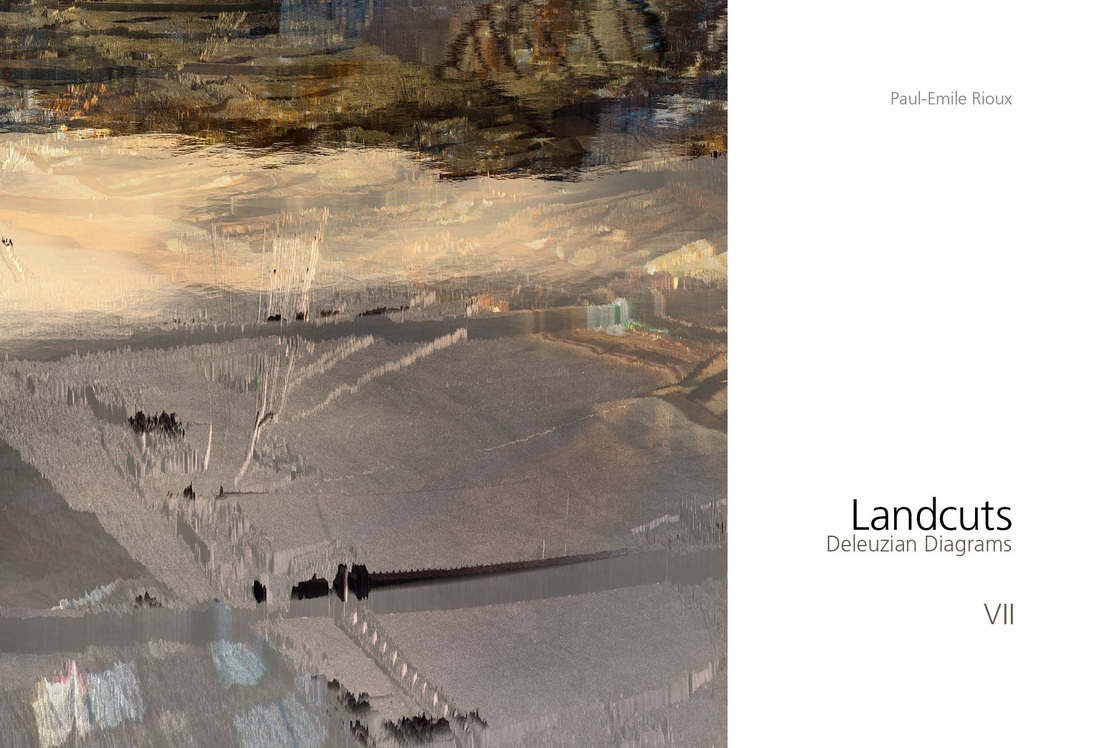

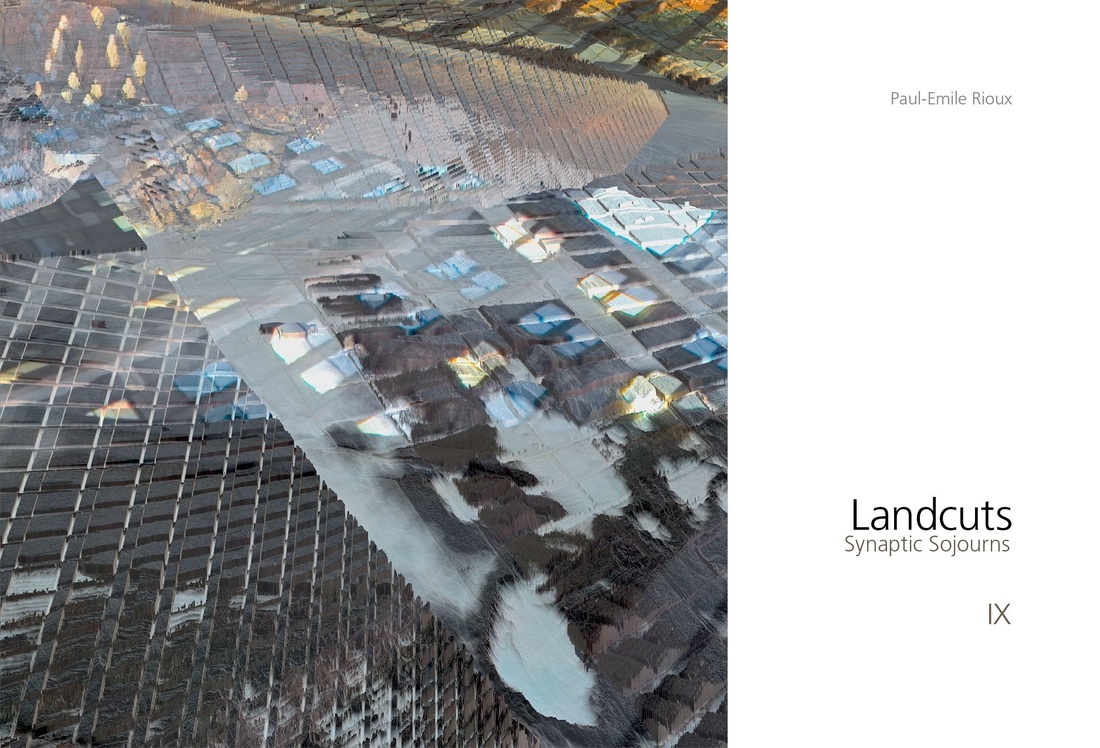

Vladimir Krstic, who lectures at the University of Kyoto, argues that the appearance of the Overexposed City is more portent than sign—that it prophesises a sign of the future deurbanization of the planet itself. Krstic holds that this process is already underway in Japanese urban space, positively fraught with myriad electronic screens. These are like black holes that suck everything around them inside an extravagant elsewhere wherein the architectural is replaced by the architectonic. Urban space enjoys not absolute transparency, but absolute opacity. And yet, even at this moment of precipitated crisis, Rioux shows us the inner guts of his cityscapes, and those “guts” seem extraordinarily neuronal.

Rioux’s version of the Overexposed City is seemingly characterized by a form of complex, modular architecture. Its multiplication, which is geometrically fractal, betray the underlying architectonic such that the contour and scope shape of the city is no longer generated by architecture; it is now generated by a flow of images in permanent evolution, by a relentless linearity that points towards infinity. The architectural surfaces in the Landcuts seem to be morphing as we view them, beyond the boundaries of neighborhood designations and discrete locales in truly fractal fashion. Thus, the division into downtown core and suburban sprawl seems to indicate that Rioux is being very tongue-in-cheek with the neural taxonomy. Virilio argues that the passage from arcane means of transport to the at-light speeds of modern telecommunications, the city of the future is the “pleasure of the interval.” [23] But Rioux’s cities are not just over-exposed, they are hyperexposed, and thus resoundingly enigmatic. In a sense, the integers inside a given Landcut are to be transposed within one’s own body image, as though they could be both internal organ transplant and ontological tattoo. Indeed, Rioux roves from image to image like a wily narrator/negotiator of our super-accelerated present tense and, in his images, offers a profound climax. Virilio dilates upon "the pathological regression of the City, in which the cosmopolis, the open city of the past, gives way to this claustropolis." [31] But are Rioux’s cities really human “claustropolises”? Are they a dark vision of the environing machine world after Skynet has achieved consciousness and dominance? Or are they rife with utopian signifiers signalling us in semaphore-like fashion that the manifestation of the human millennium is at hand? Notes: See Paul Virilio, City of Panic, trans. Julie Rose (London, UK: Berg Publishers, 2007). |

|

Rioux’s cities are not just over-exposed, they are hyperexposed.

|