The City, Downtown, The Suburb

|

Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

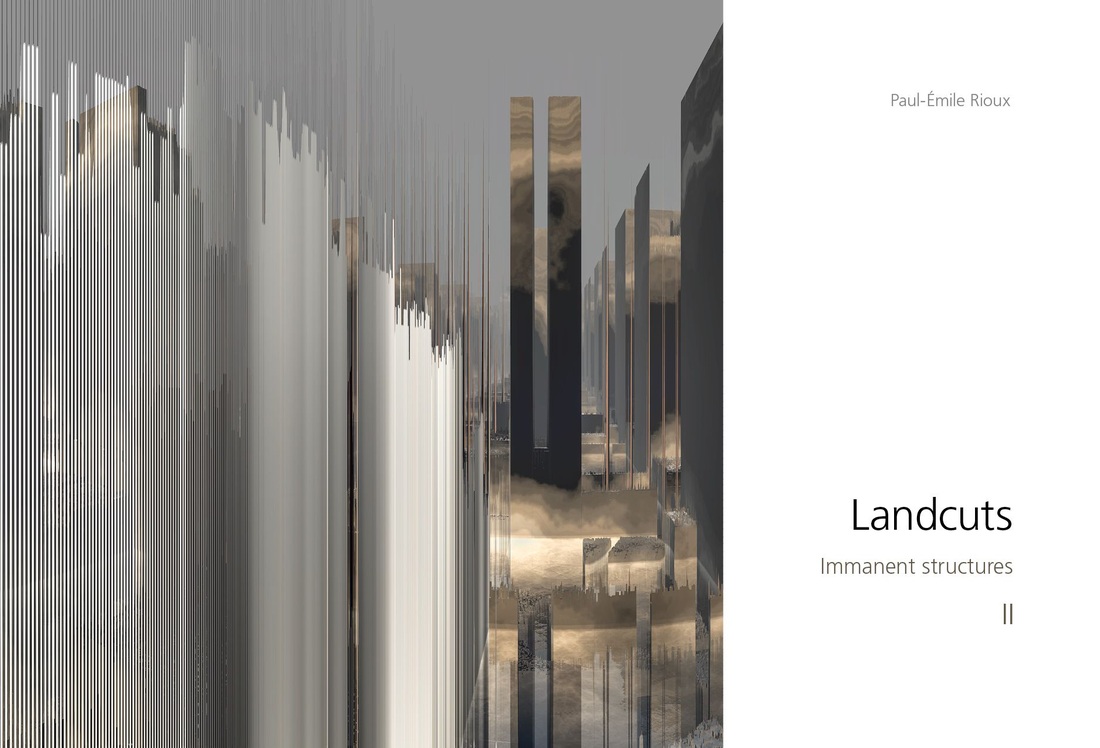

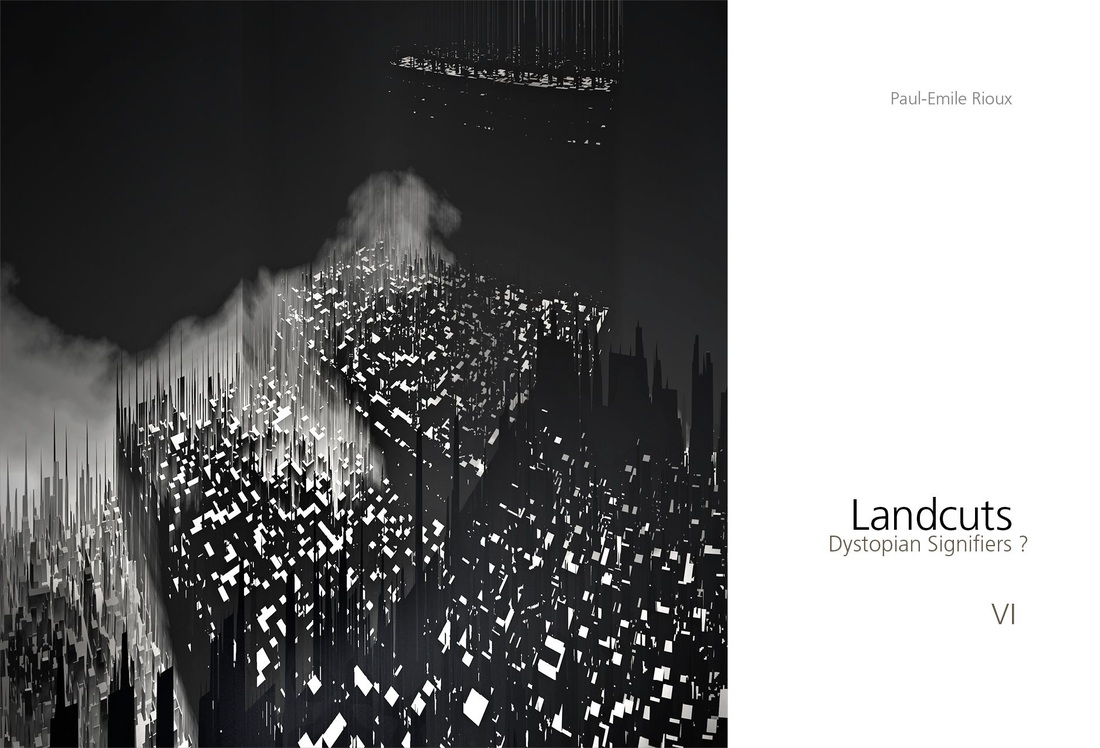

All three recent series of Landcuts highlight what I call their status as “immanent structures.” I do not mean to invoke philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence, in which the divine is perceived as being somehow integral to or foundational of the material world. I mean it more in the sense of “remaining within,” in-dwelling, layered inhabitation. For as the optic moves across the surface of these landcuts, the structures seem like cascades of immanent housing façades, armatures for something or someone that dwells within. But housing for what—or for whom?

In his final essay entitled “Immanence: A Life,” French philosopher Gilles Deleuze writes, "It is only when immanence is no longer immanence to anything other than itself that we can speak of a plane of immanence." [2] As a formative value, he uses the term in the meaning of a pure immanence, a phenomenal embeddedness. It is most useful to consider it in terms of Rioux’s work wherein the pure plane seems synonymous with an infinitely unfolding field or quintessentially smooth space without inflective division; here is a rhizomatic entity with innumerable tendrils that reach up and over the threshold of eternity like weeds in hyperspace. |

|

We have the sense in Rioux’s work of a -progressively unfolding, indigenous network of forces, clones, binary -connections, myriad relations, and endless becomings

|

|

The plane of immanence latent in Rioux’s overwhelmingly horizonal work—in the phenomenological sense of a horizon that extends backwards and forwards, and encompasses time, space and a human subject—helps explain the phenomenal consistency of his works across a broad array of structural incarnations, and what we might characterize as the implacable nature of their innate, unfolding logic. As a geometric plane, it is wed ineluctably to a virtual design rather than a mental construct. And yet, it grounds us within it with a certain degree of finality, and carries us forward. Now, for Deleuze, that latent design is the ontological itself. And perhaps what lends Rioux’s landcuts their disconcerting resonance is the sense of an inhering ontology and problematic emplacement therein. In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Félix Guattari develop further the notion of a plane of immanence: "Here, there are no longer any forms or developments of forms; nor are there subjects or the formation of subjects. There is no structure, any more than there is genesis." [3]

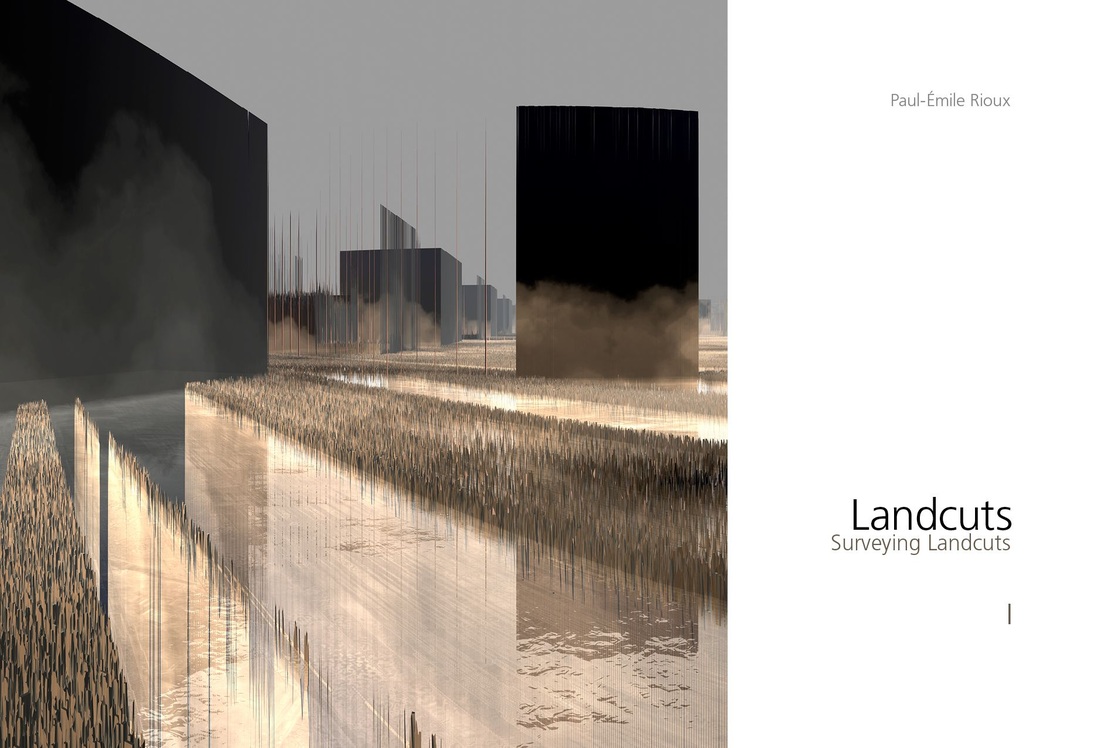

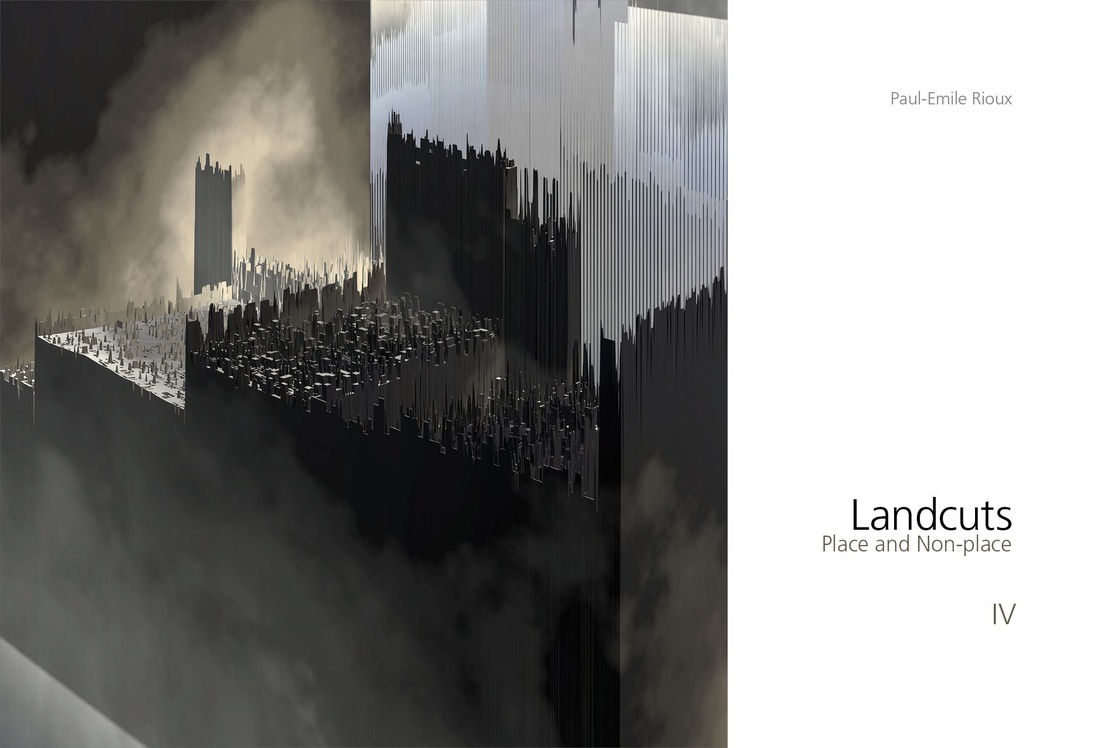

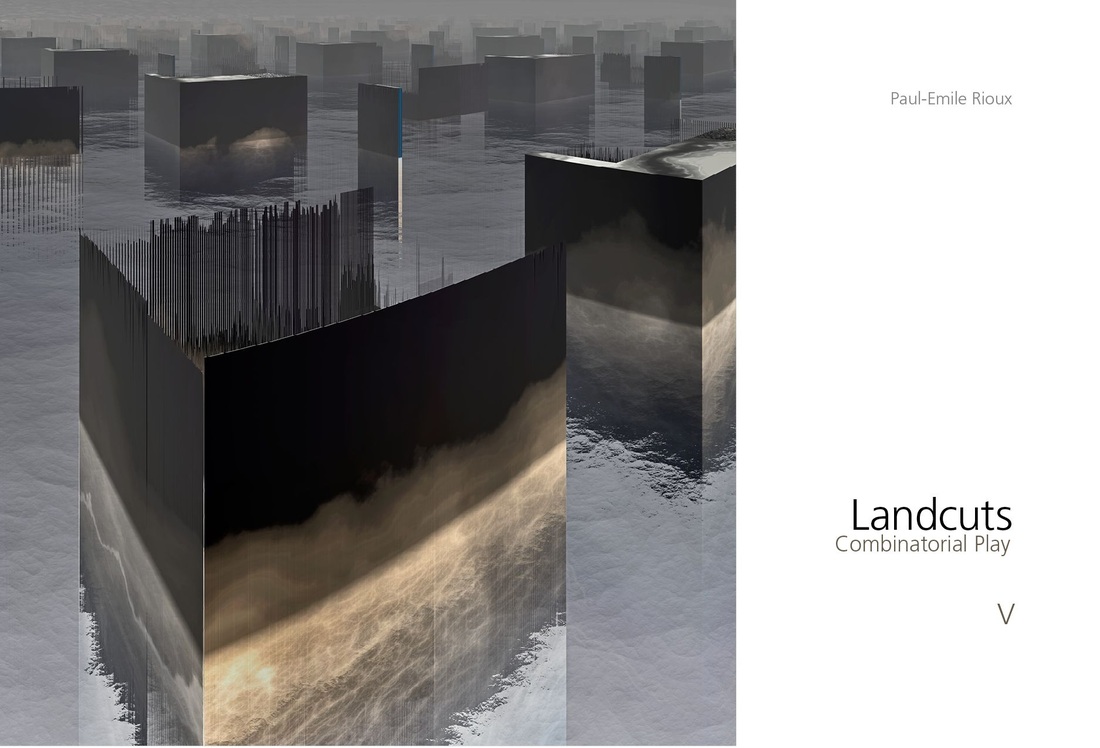

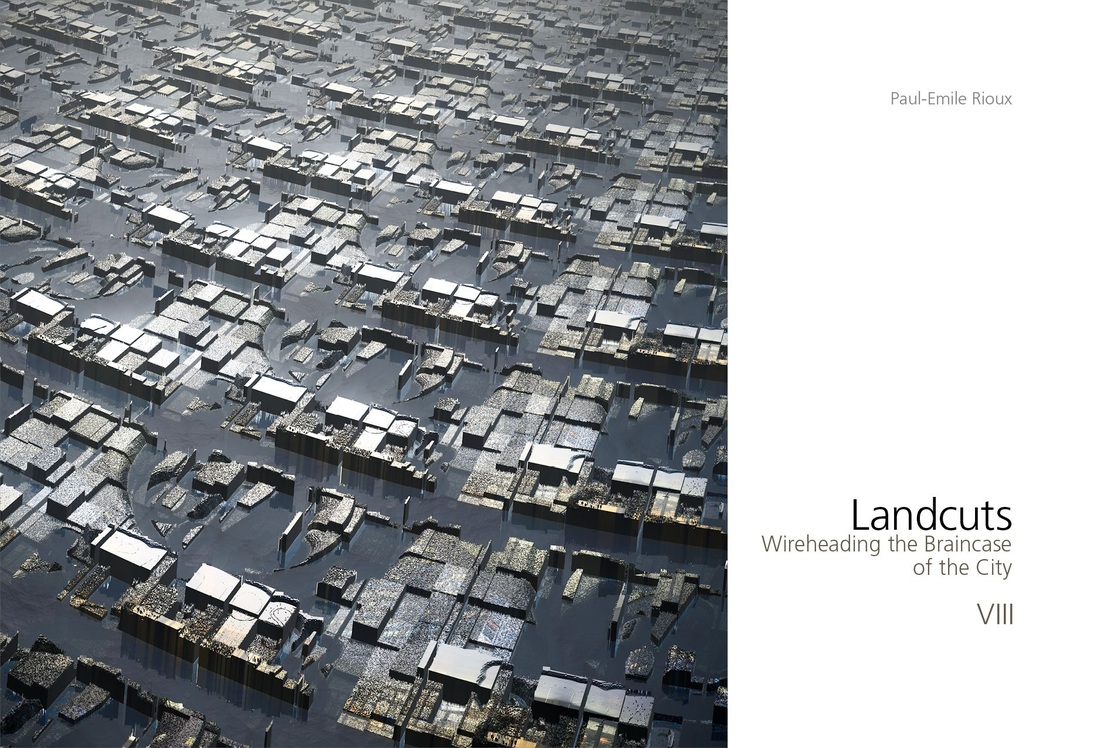

In Rioux’s cities, such as B1-, massive structures seem to walk on water, float in an aqueous space—like the humor located in the anterior and posterior chambers of the human eye—with all the grace of equilateral polygons in amazing fractal profusion. In B3-The City, the radial edges of the structures suggest fractal geometries beyond our ken. These weird structures seem to mutate and spontaneously multiply across the broad array of the cityscape like a dividing cell. In other works from The City series, the fractal dimensionality of black monoliths reminds us of the omniscient icon from Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. |

|

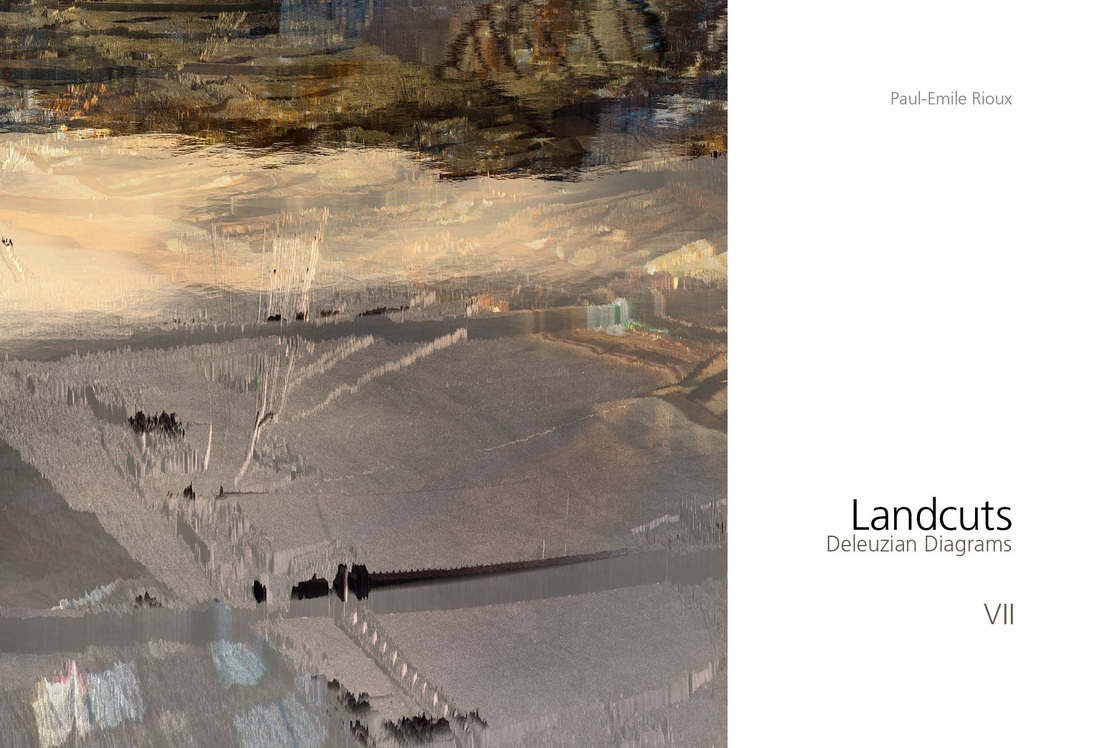

The latitudes and longitudes of Rioux’s extraordinary homeworlds are given in an unfolding of their inherent cartographies as though on a cosmic scale but here and now assimilable in the foreground and background as an interwoven skein of signs that disclose an environing world with a vast multiplicity of kinetic, endlessly receding interrelationships.

|

|

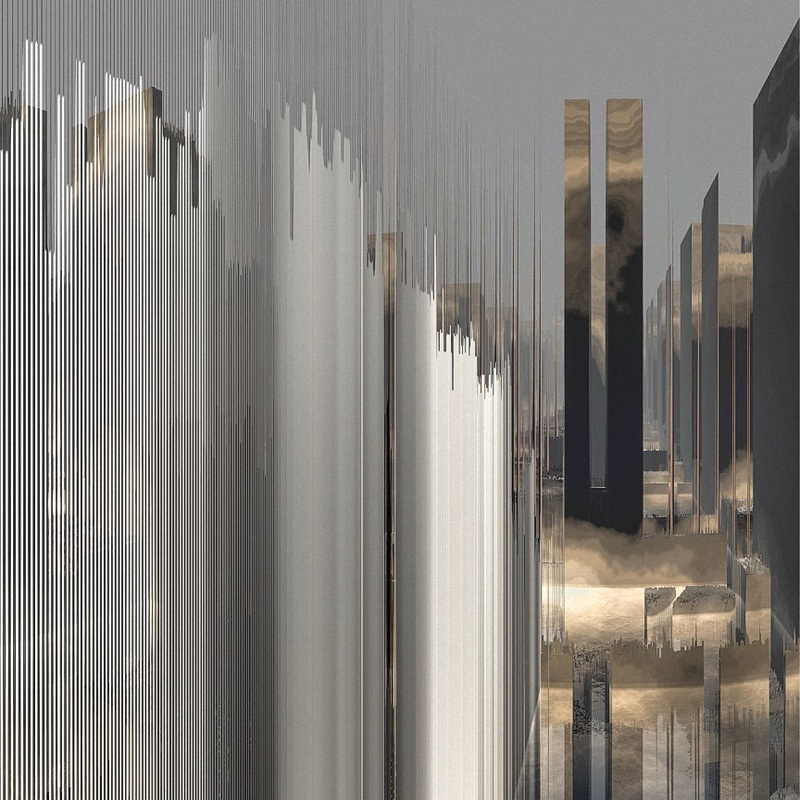

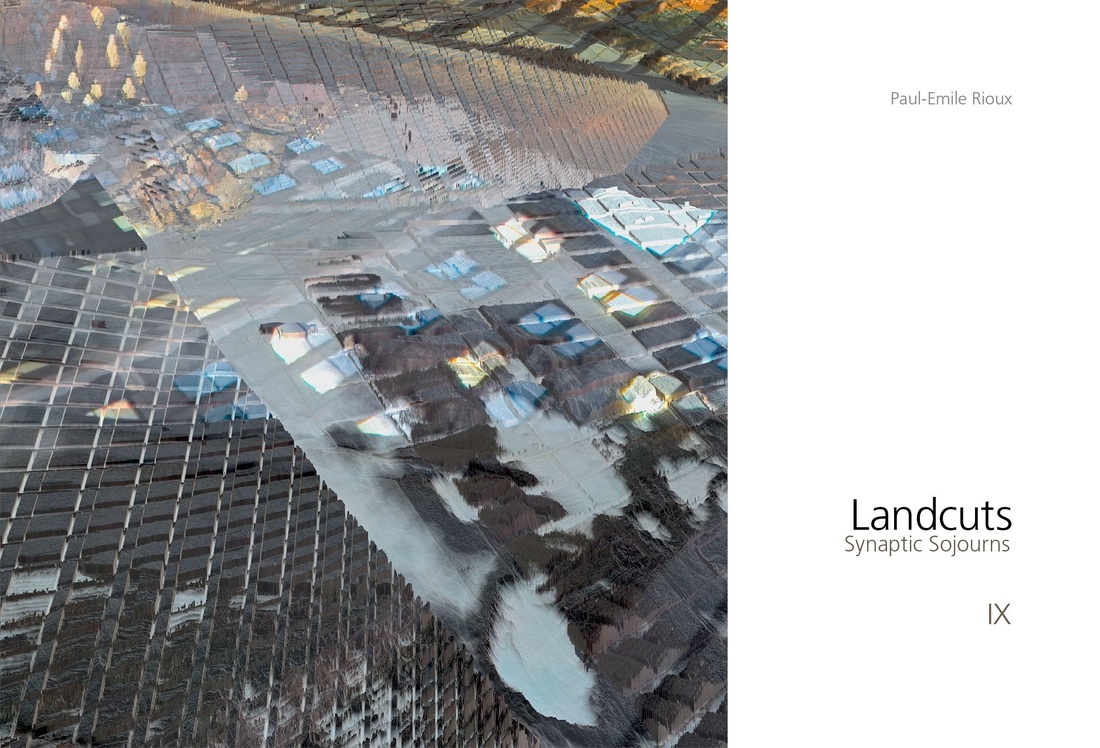

Here fields of force prescribe regional structural ontologies that catch us up within them and hold our attention like insects in amber. We have the sense in Rioux’s work of a progressively unfolding, indigenous network of forces, clones, binary connections, myriad relations, and endless becomings: "There are only relations of movement and rest, speed and slowness between unformed elements, or at least between elements that are relatively unformed, molecules, and particles of all kinds. There are only haecceities, affects, subjectless individuations that constitute collective assemblages." [4] The collective assemblages mirror those in Rioux’s B2-1-Downtown, a remarkable evocation of the downtown core, with the ceaseless multiplication of structures that seem poised on the threshold of eternity. In B2-3-Downtown, the radial edge of the downtown core is like the prow of some gigantic ship, with a cloud-like backdrop that suggests deep space and genesis at once.

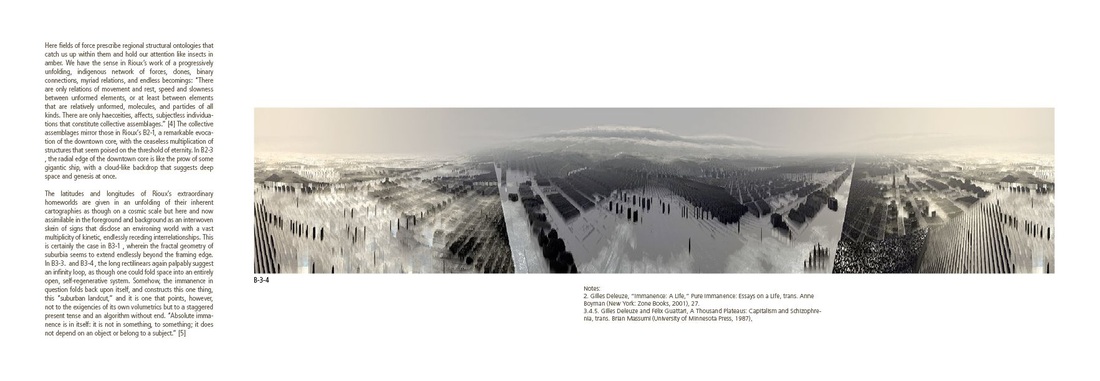

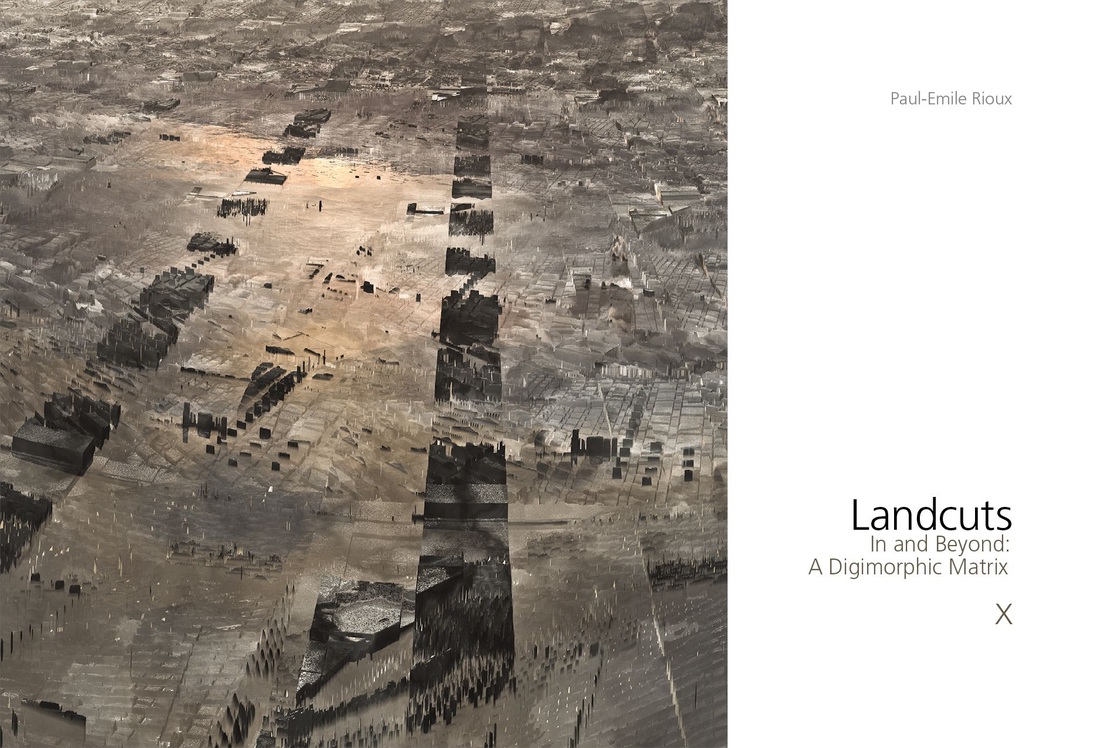

The latitudes and longitudes of Rioux’s extraordinary homeworlds are given in an unfolding of their inherent cartographies as though on a cosmic scale but here and now assimilable in the foreground and background as an interwoven skein of signs that disclose an environing world with a vast multiplicity of kinetic, endlessly receding interrelationships. This is certainly the case in B3-1, wherein the fractal geometry of suburbia seems to extend endlessly beyond the framing edge. In B3-3- The Suburb No. and B3-4- The Suburb No. , the long rectilinears again palpably suggest an infinity loop, as though one could fold space into an entirely open, self-regenerative system. Somehow, the immanence in question folds back upon itself, and constructs this one thing, this “suburban landcut,” and it is one that points, however, not to the exigencies of its own volumetrics but to a staggered present tense and an algorithm without end. "Absolute immanence is in itself: it is not in something, to something; it does not depend on an object or belong to a subject." [5] Notes: 2. Gilles Deleuze, “Immanence: A Life,” Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life, trans. Anne Boyman (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 27. 3.4.5. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), |