ETC MEDIA 103 REVUE D’ARTS MÉDIATIQUES February 2016

The City on the Edge of Forever:

The Digital Environment of Paul-Emile RiouxJames D. Campbell

In “The City on the Edge of Forever”, the penultimate episode of the first season of the American science fiction television series Star Trek (broadcast on April 6, 1967), the crew of the starship USS -Enterprise discover a portal through space and time, a living time -machine called “The Guardian of Forever.” Captain James Kirk and First -Officer Spock are permitted by the machine to pursue a crazed Dr. McCoy through the portal in order to repair the timeline that he has breached, -accidentally altering history and murdering their collective future. Kirk and Spock arrive in New York City during the 1930s Great -Depression, and make the repair. They return through the portal. The Guardian then says, “Time has resumed its shape. All is as it was before. Many such journeys are possible. Let me be your gateway.”

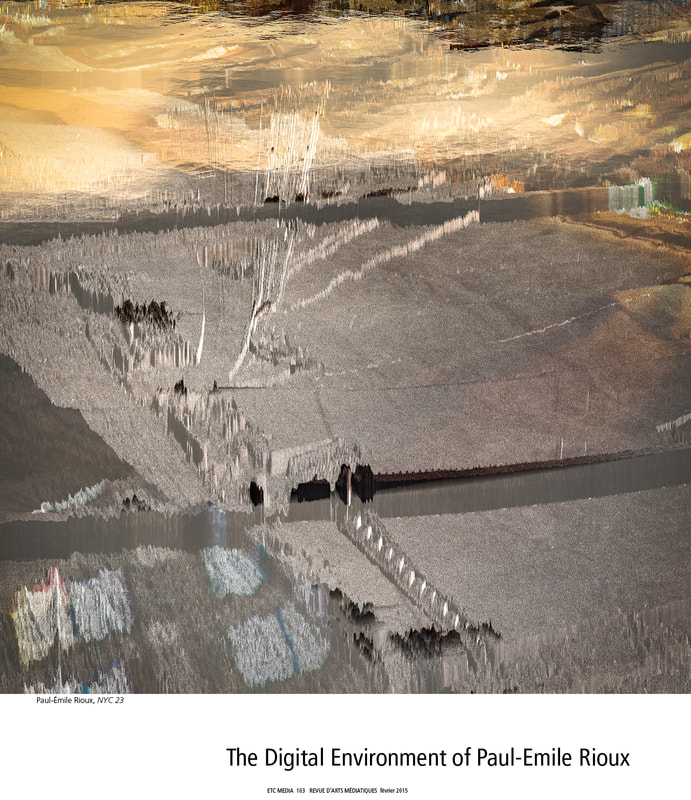

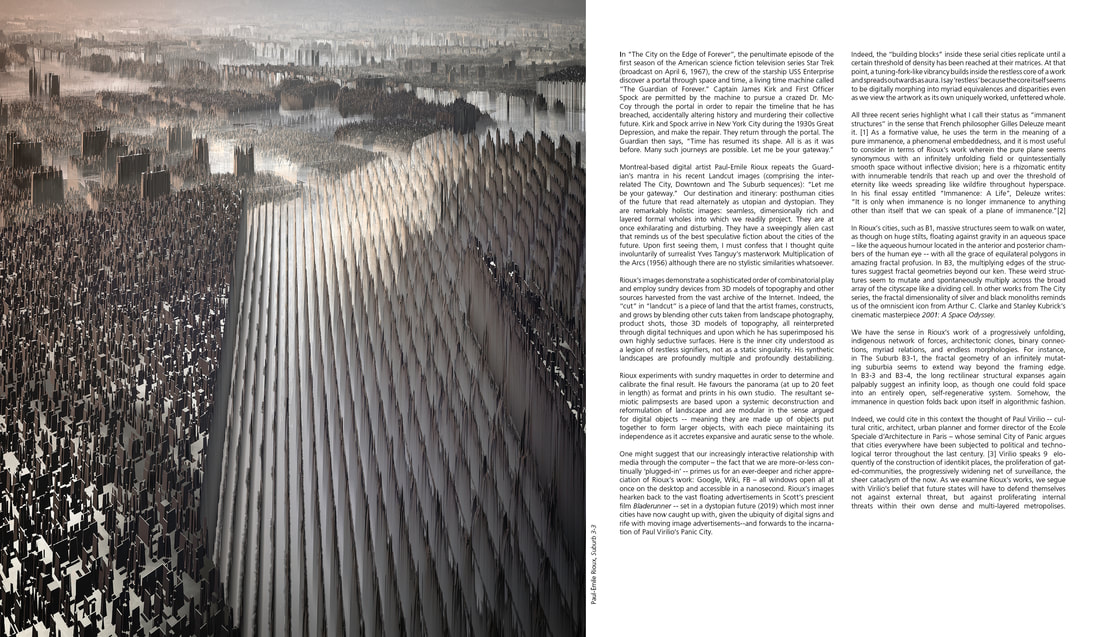

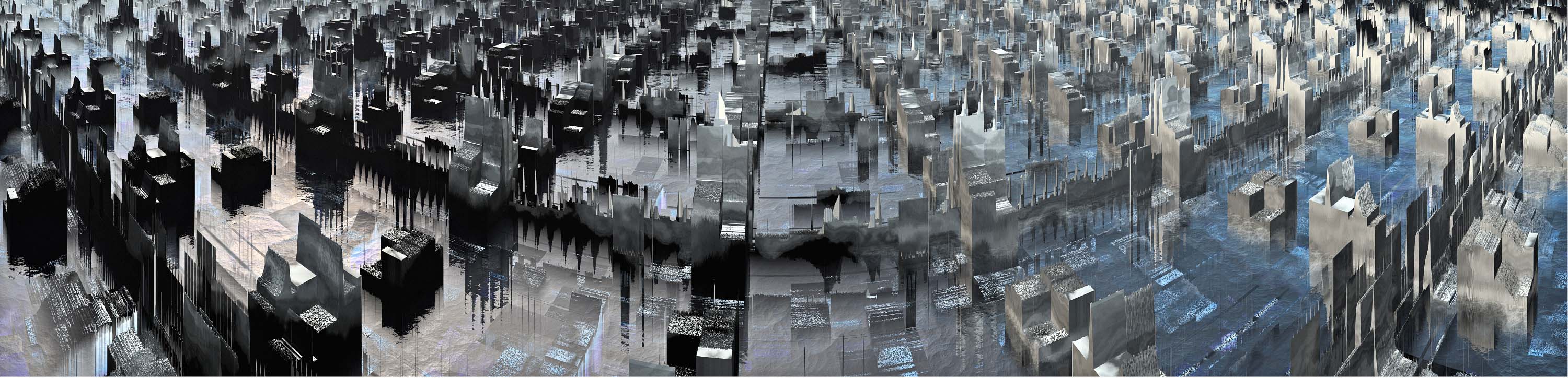

Montreal-based digital artist Paul-Emile Rioux repeats the Guardian’s mantra in his recent Landcut images (comprising the interrelated The City, Downtown and The Suburb sequences): “Let me be your -gateway.” Our destination and itinerary: posthuman cities of the future that read alternately as utopian and dystopian. They are remarkably holistic images: seamless, dimensionally rich and -layered formal wholes into which we readily project. They are at once -exhilarating and disturbing. They have a sweepingly alien cast that -reminds us of the best speculative fiction about the cities of the future. Upon first seeing them, I must confess that I thought quite -involuntarily of surrealist Yves Tanguy’s masterwork Multiplication of the Arcs (1956) although there are no stylistic similarities whatsoever. Rioux’s images demonstrate a sophisticated order of combinatorial play and employ sundry devices from 3D models of topography and other sources harvested from the vast archive of the Internet. Indeed, the “cut” in “landcut” is a piece of land that the artist frames, constructs, and grows by blending other cuts taken from landscape -photography, product shots, those 3D models of topography, all reinterpreted through digital techniques and upon which he has superimposed his own highly seductive surfaces. Here is the inner city understood as a legion of restless signifiers, not as a static singularity. His -synthetic landscapes are profoundly multiple and profoundly destabilizing. Rioux experiments with sundry maquettes in order to determine and calibrate the final result. He favours the panorama (at up to 20 feet in length) as format and prints in his own studio. The -resultant semiotic palimpsests are based upon a systemic -deconstruction and reformulation of landscape and are modular in the sense -argued for digital objects -- meaning they are made up of objects put -together to form larger objects, with each piece maintaining its -independence as it accretes expansive and auratic sense to the whole. One might suggest that our increasingly interactive relationship with media through the computer – the fact that we are more-or-less continually ‘plugged-in’ -- primes us for an ever-deeper and richer appreciation of Rioux’s work: Google, Wiki, FB – all windows open all at once on the desktop and accessible in a nanosecond. Rioux’s images hearken back to the vast floating advertisements in Scott’s prescient film Bladerunner -- set in a dystopian future (2019) which most inner cities have now caught up with, given the ubiquity of digital signs and rife with moving image -advertisements--and forwards to the incarnation of Paul Virilio’s Panic City. Rioux’s cities on the edge of forever possess unusual -gravitas, breathtaking vistas and epic sweep. They embody an iteration of simplicity upon which all modern computing is based. -Indeed, their endless structural facades emulate the extraordinary computational power of electrified binary numerics. -Untold legions of busy nanobots seem to be at work building here, testing existing definitions of place, space and emplacement. Indeed, the “building blocks” inside these serial cities replicate until a certain threshold of density has been reached at their matrices. At that point, a tuning-fork-like vibrancy builds inside the restless core of a work and spreads outwards as aura. I say ‘restless’ because the core itself seems to be digitally morphing into myriad equivalences and disparities even as we view the artwork as its own uniquely worked, unfettered whole. All three recent series highlight what I call their status as -“immanent structures” in the sense that French philosopher Gilles Deleuze meant it. [1] As a formative value, he uses the term in the meaning of a pure immanence, a phenomenal embeddedness, and it is most useful to consider in terms of Rioux’s work wherein the pure plane seems synonymous with an infinitely unfolding field or -quintessentially smooth space without inflective division; here is a rhizomatic -entity with innumerable tendrils that reach up and over the threshold of eternity like weeds spreading like wildfire throughout hyperspace. In his final essay entitled “Immanence: A Life”, Deleuze writes: “It is only when immanence is no longer immanence to anything -other than itself that we can speak of a plane of immanence.”[2] In Rioux’s cities, such as B1, massive structures seem to walk on -water, as though on huge stilts, floating against gravity in an aqueous space – like the aqueous humour located in the anterior and -posterior chambers of the human eye -- with all the grace of equilateral -polygons in amazing fractal profusion. In B3, the multiplying edges of the structures suggest fractal geometries beyond our ken. These weird structures seem to mutate and spontaneously multiply across the broad array of the cityscape like a dividing cell. In other works from The City series, the fractal dimensionality of silver and black monoliths reminds us of the omniscient icon from Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. We have the sense in Rioux’s work of a progressively unfolding, -indigenous network of forces, architectonic clones, binary connections, myriad relations, and endless morphologies. For instance, in The Suburb B3-1, the fractal geometry of an infinitely mutating suburbia seems to extend way beyond the framing edge. In B3-3 and B3-4, the long rectilinear structural expanses again -palpably suggest an infinity loop, as though one could fold space into an entirely open, self-regenerative system. Somehow, the -immanence in question folds back upon itself in algorithmic fashion. Indeed, we could cite in this context the thought of Paul Virilio -- cultural critic, architect, urban planner and former director of the Ecole Speciale d’Architecture in Paris – whose seminal City of Panic argues that cities everywhere have been subjected to political and technological terror throughout the last century. [3] Virilio speaks -9 eloquently of the construction of identikit places, the proliferation of gated-communities, the progressively widening net of surveillance, the sheer cataclysm of the now. As we examine Rioux’s works, we segue with Virilio’s belief that future states will have to defend -themselves not against external threat, but against proliferating -internal threats within their own dense and multi-layered metropolises. |

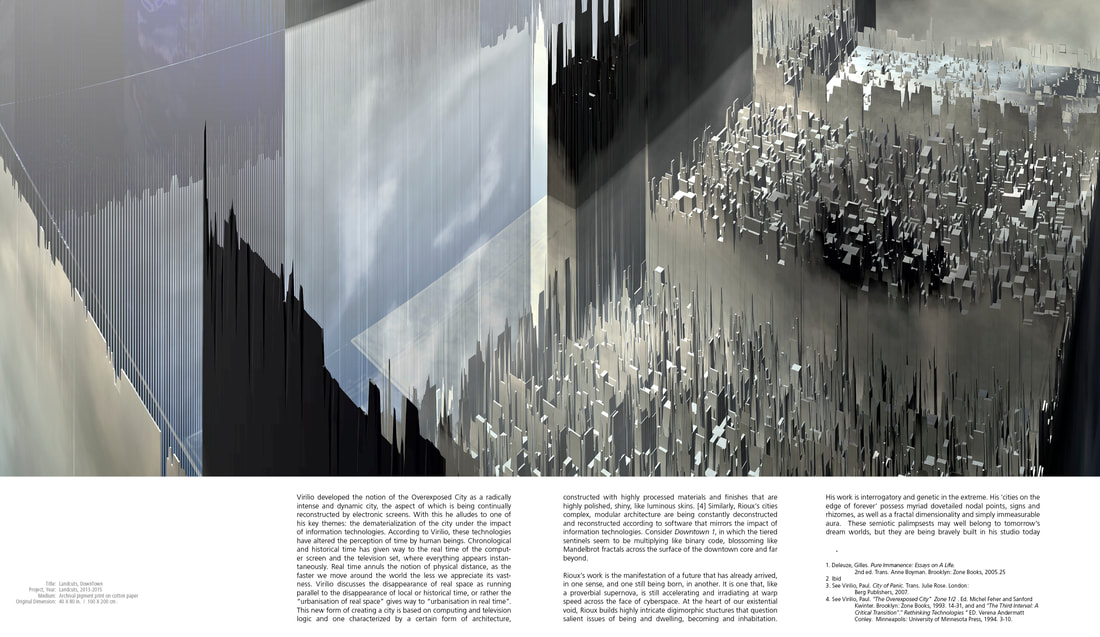

Virilio developed the notion of the Overexposed City as a radically intense and dynamic city, the aspect of which is being continually reconstructed by electronic screens. With this he alludes to one of his key themes: the dematerialization of the city under the impact of information technologies. According to Virilio, these technologies have altered the perception of time by human beings. Chronological and historical time has given way to the real time of the computer screen and the television set, where everything appears instantaneously. Real time annuls the notion of physical distance, as the faster we move around the world the less we appreciate its vastness. Virilio discusses the disappearance of real space as running parallel to the disappearance of local or historical time, or rather the -“urbanisation of real space” gives way to “urbanisation in real time”.

This new form of creating a city is based on computing and -television logic and one characterized by a certain form of architecture, constructed with highly processed materials and finishes that are -highly polished, shiny, like luminous skins. [4] Similarly, Rioux’s cities complex, modular architecture are being constantly deconstructed and reconstructed according to software that mirrors the impact of information technologies. Consider Downtown 1, in which the tiered -sentinels seem to be multiplying like binary code, blossoming like Mandelbrot fractals across the surface of the downtown core and far beyond. Rioux’s work is the manifestation of a future that has already arrived, in one sense, and one still being born, in another. It is one that, like a proverbial supernova, is still accelerating and irradiating at warp speed across the face of cyberspace. At the heart of our existential void, Rioux builds highly intricate digimorphic stuctures that -question salient issues of being and dwelling, becoming and inhabitation. His work is interrogatory and genetic in the extreme. His ‘cities on the edge of forever’ possess myriad dovetailed nodal points, signs and rhizomes, as well as a fractal dimensionality and simply -immeasurable aura. These semiotic palimpsests may well belong to tomorrow’s dream worlds, but they are being bravely built in his studio today. 1. Deleuze, Gilles. Pure Immanence: Essays on A Life. 2nd ed. Trans. Anne Boyman. Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2005.25 2 Ibid 3. See Virilio, Paul. City of Panic. Trans. Julie Rose. London: Berg Publishers, 2007. 4. See Virilio, Paul. “The Overexposed City” Zone 1/2 . Ed. Michel Feher and Sanford Kwinter. Brooklyn: Zone Books, 1993. 14-31, and and “The Third Interval: A Critical Transition”.” Rethinking Technologies “ ED. Verena Andermatt Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. 3-10. |