Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari use the term “rhizome” to describe a web of heterogenous multiplicities, non-hierarchical entry and exit points in data representation and interpretation. Inside this web, every point is connected to every other point. In A Thousand Plateaus, they develop the concept, lifted from biology, of a state of constant becoming, unfolding and progressive organic development rather than stasis and blockage.

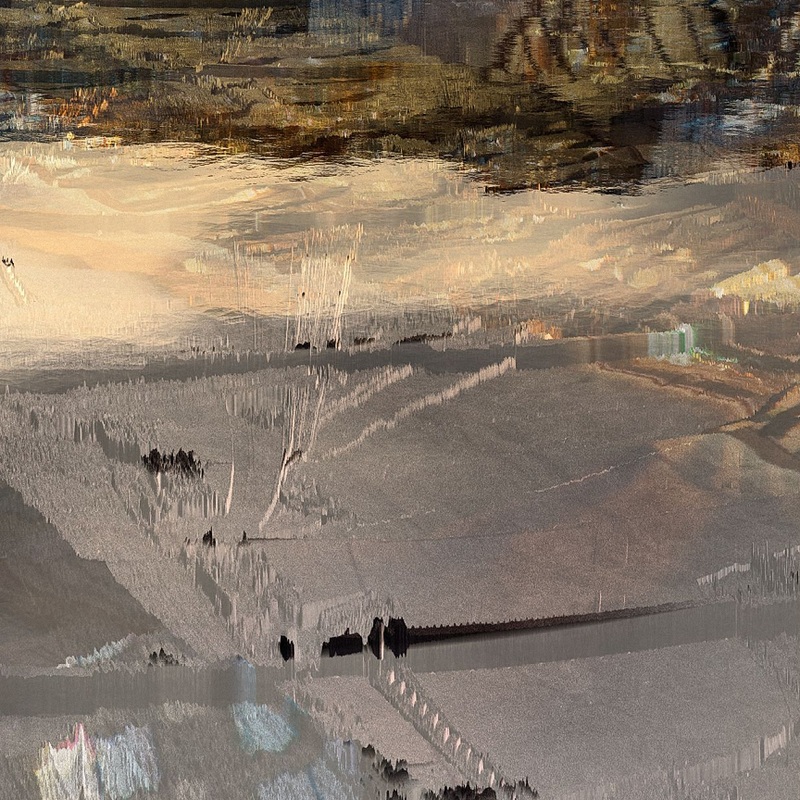

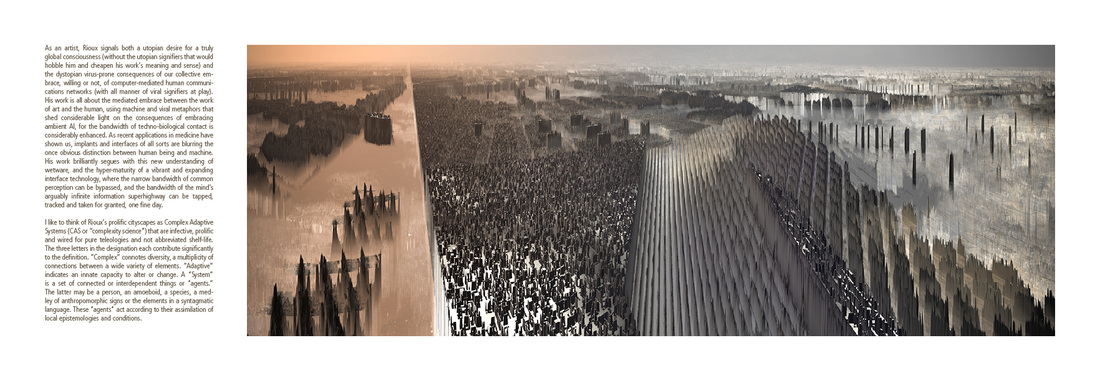

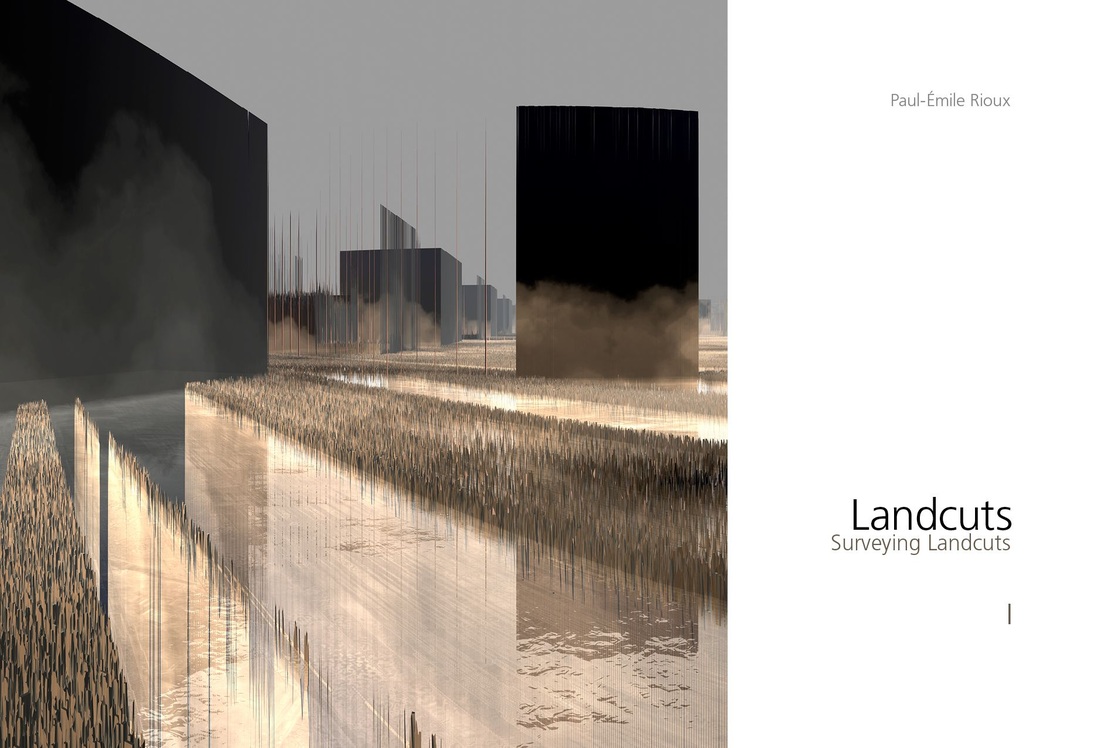

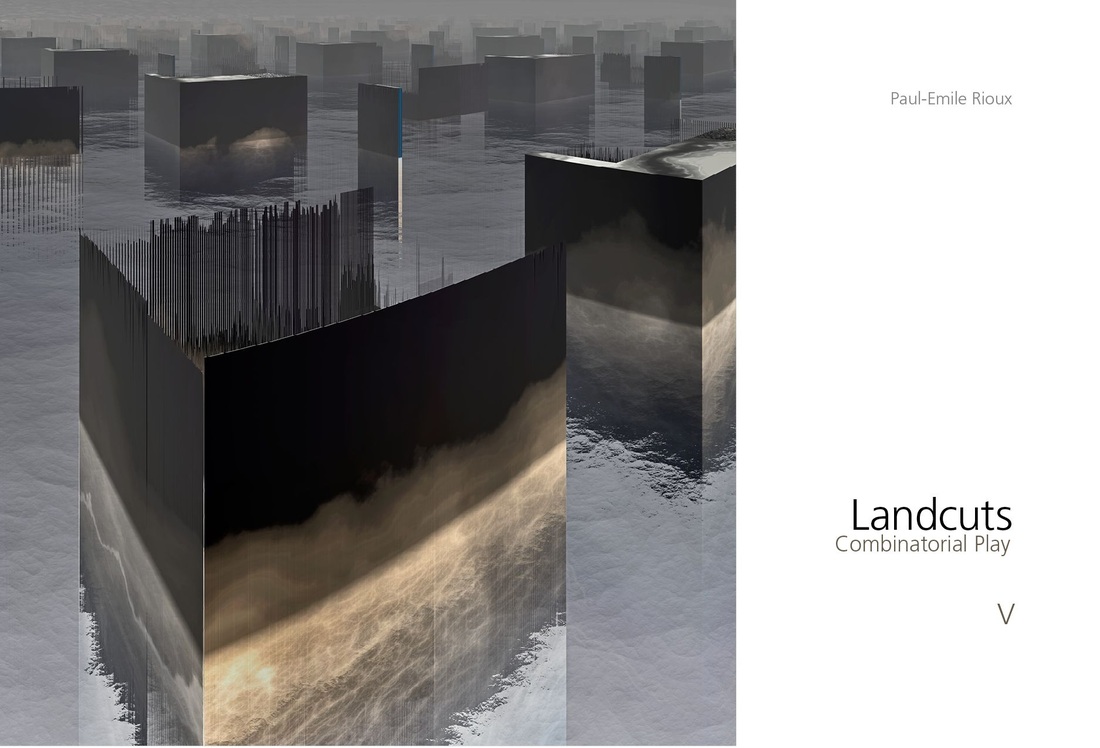

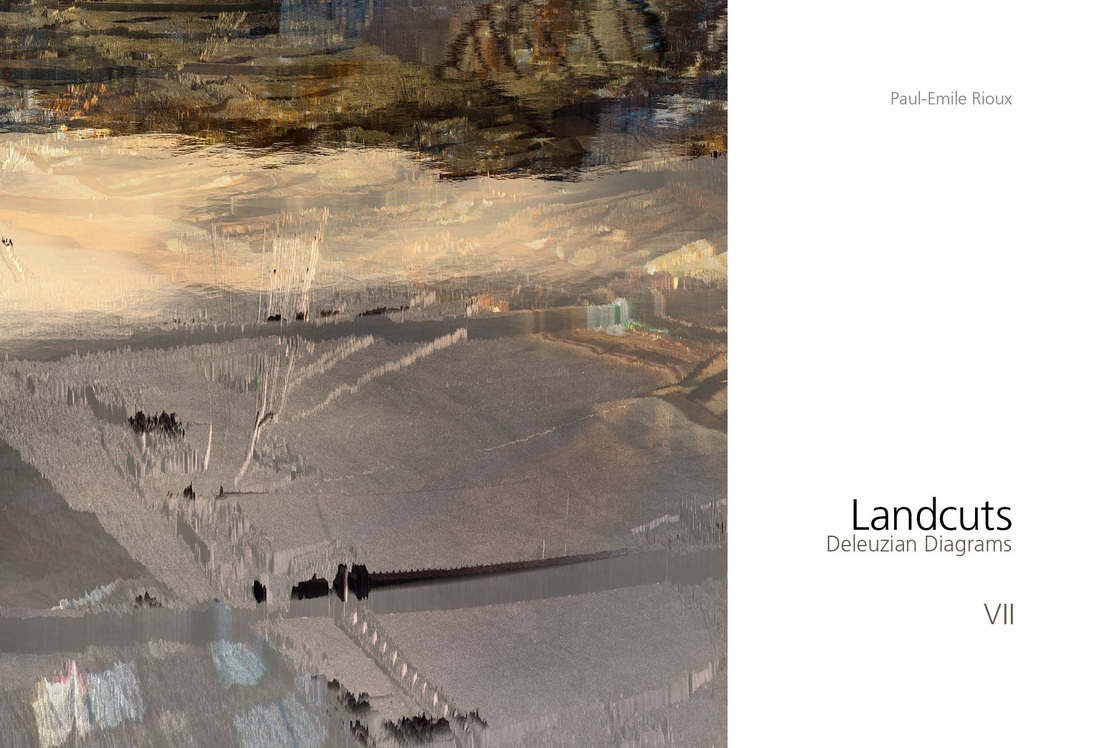

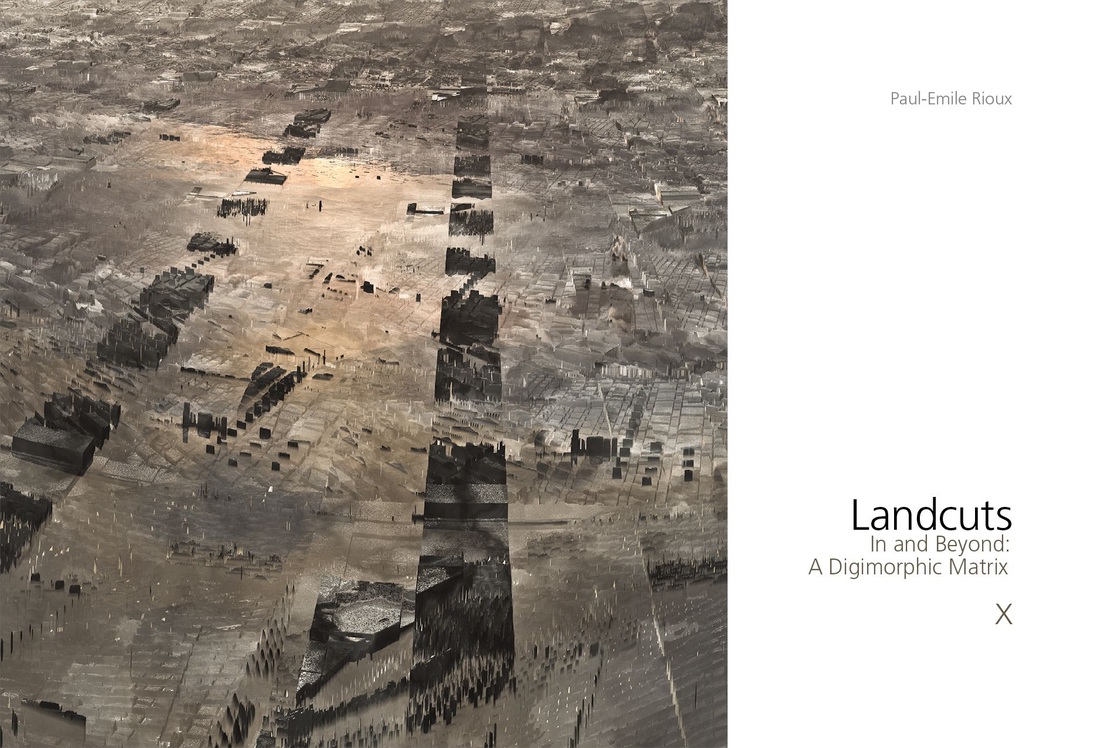

A Rioux cityscape has, like a rhizome, “no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo." [25] It is based on a nomadic system of generative intensity and ceaseless propagation. Beneath any on surface there lies another, like the multiple skins of an onion, leading ineluctably inwards to a still unseen generative core. Deleuze and Guattari state that, “Unlike the graphic arts, drawing, or photography, unlike tracings, the rhizome pertains to a map that must be produced, constructed, a map that is always detachable, connectable, reversible, modifiable, and has multiple entryways and exits and its own lines of flight.” [26] Rioux’s works are similarly acentered and wholly detachable when understood as maps, animated by a restless circulation of interior states, and ruled by the short codes of late Modernity. They have to be, because to privilege one perspective or compass point would be to invite taxonomy, inertia and wholesale closure. The signs in these works are forever on the prowl. And the appointed prey is none other than our own grayware. |

|

Rioux’s works effectively illustrate and enact on the threshold we have only now reached as a telematic culture.

|

|

I like to think of Rioux’s prolific cityscapes as Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS or “complexity science”) that are infective, prolific and wired for pure teleologies and not abbreviated shelf-life.

|

|

The topicality and cutting-edge resonance of these works is worth mentioning, because they speak directly to this tense we inhabit—they speak to the time we are living now: Supermodernity, as French thinker Marc Augé recently defined it, which we inhabit like mindless drones, aware that the future is literally nipping at our heels as we dance a tarantella on the shared roof of human and machine intelligence towards the ultimate temporal (human) truth, the inevitability of our own death, prefigured in the short code of the computer and the long code of the DNA helix. [27] We are living now on the very cusp of a tremulous merger of humans and the technologies they have brought into being, and that we will continue to merge with, both metaphorically and in the most somatic and obvious social sense, for decades to come. Rioux’s works effectively illustrate and enact on the threshold we have only now reached as a telematic culture. As we continue to surround ourselves with myriad telecommunications and informatics (also known as ICT–Info and Communications Technology), the Landcuts of Rioux will only become ever more resonant an index for our transformation.

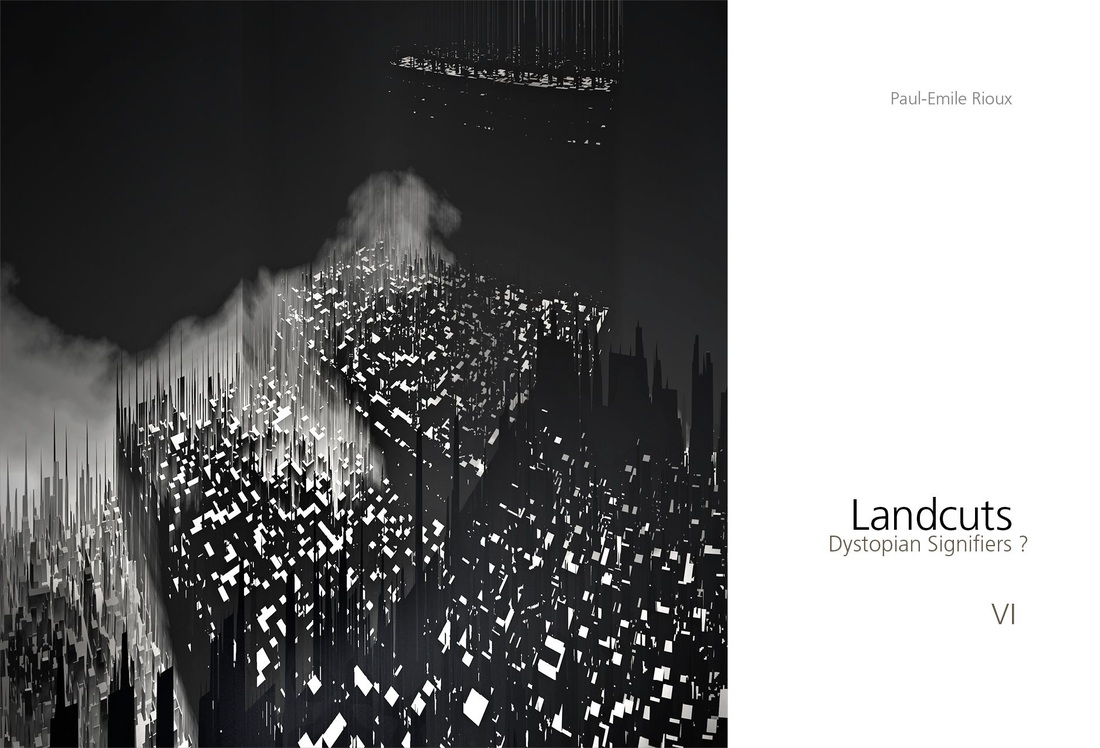

As an artist, Rioux signals both a utopian desire for a truly global consciousness (without the utopian signifiers that would hobble him and cheapen his work’s meaning and sense) and the dystopian virus-prone consequences of our collective embrace, willing or not, of computer-mediated human communications networks (with all manner of viral signifiers at play). His work is all about the mediated embrace between the work of art and the human, using machine and viral metaphors that shed considerable light on the consequences of embracing ambient AI, for the bandwidth of techno-biological contact is considerably enhanced. As recent applications in medicine have shown us, implants and interfaces of all sorts are blurring the once obvious distinction between human being and machine. His work brilliantly segues with this new understanding of wetware, and the hyper-maturity of a vibrant and expanding interface technology, where the narrow bandwidth of common perception can be bypassed, and the bandwidth of the mind’s arguably infinite information superhighway can be tapped, tracked and taken for granted, one fine day. |

|

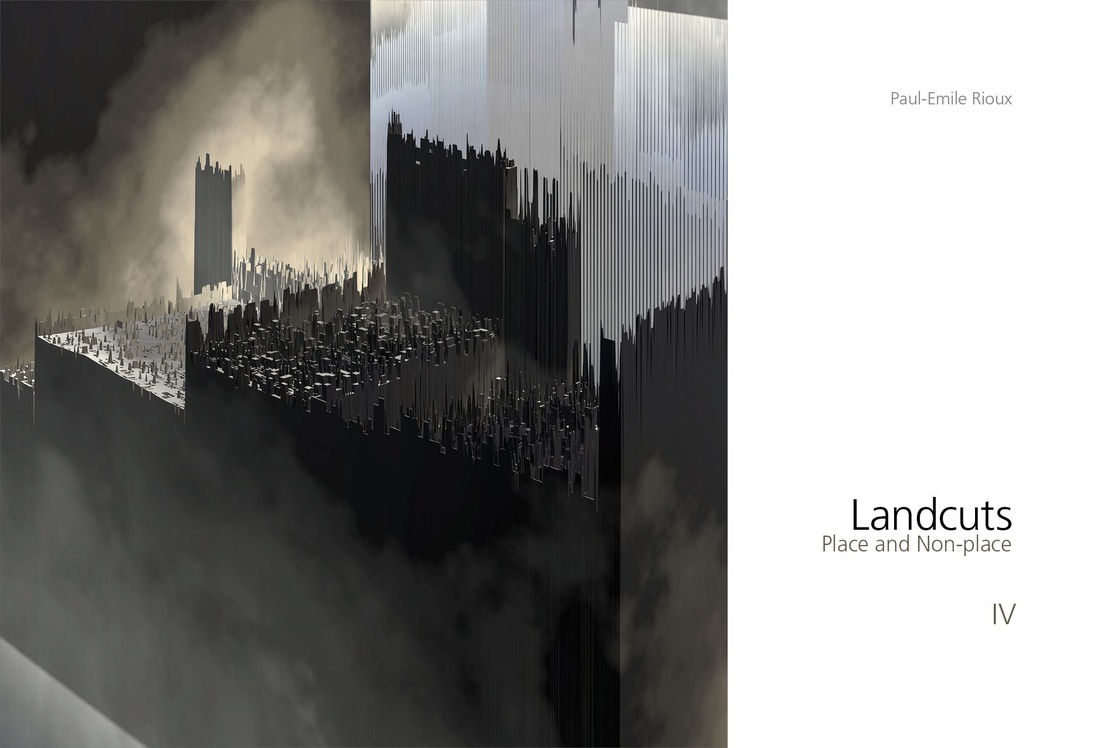

Rioux cityscape is like an anarchic/anamorphic/semaphoric virus with no apparent control centre or central agency but an infinite network of automata that freely channels information from one sector to another without hindrance.

|

|

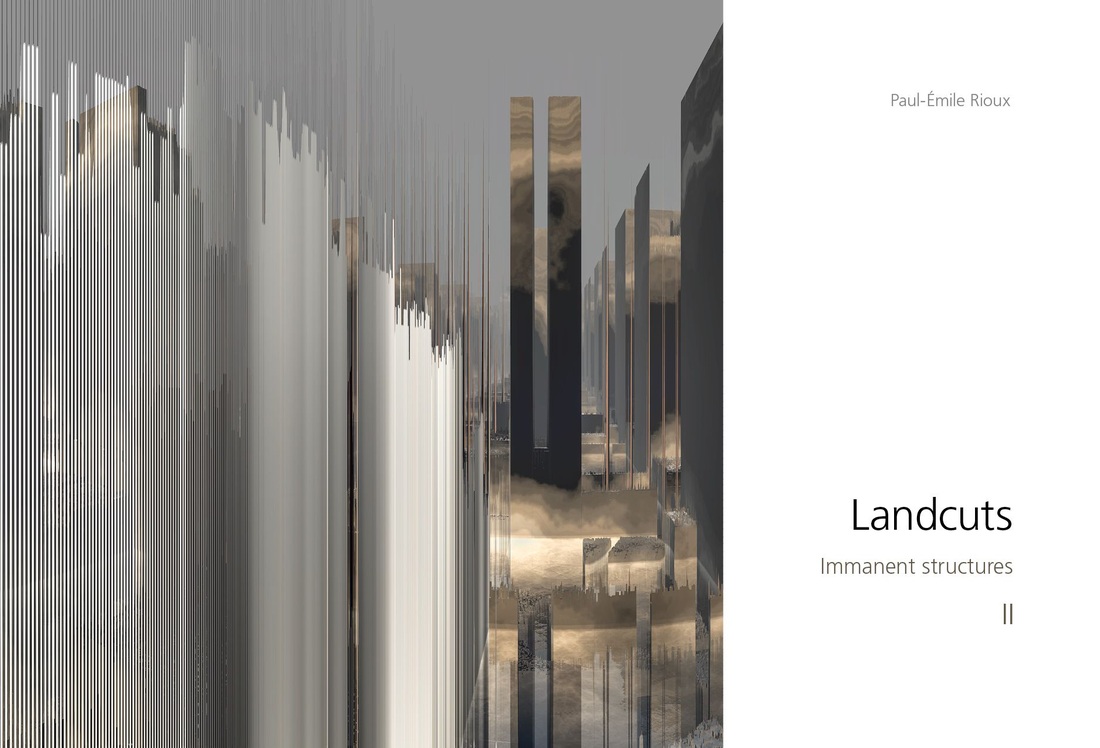

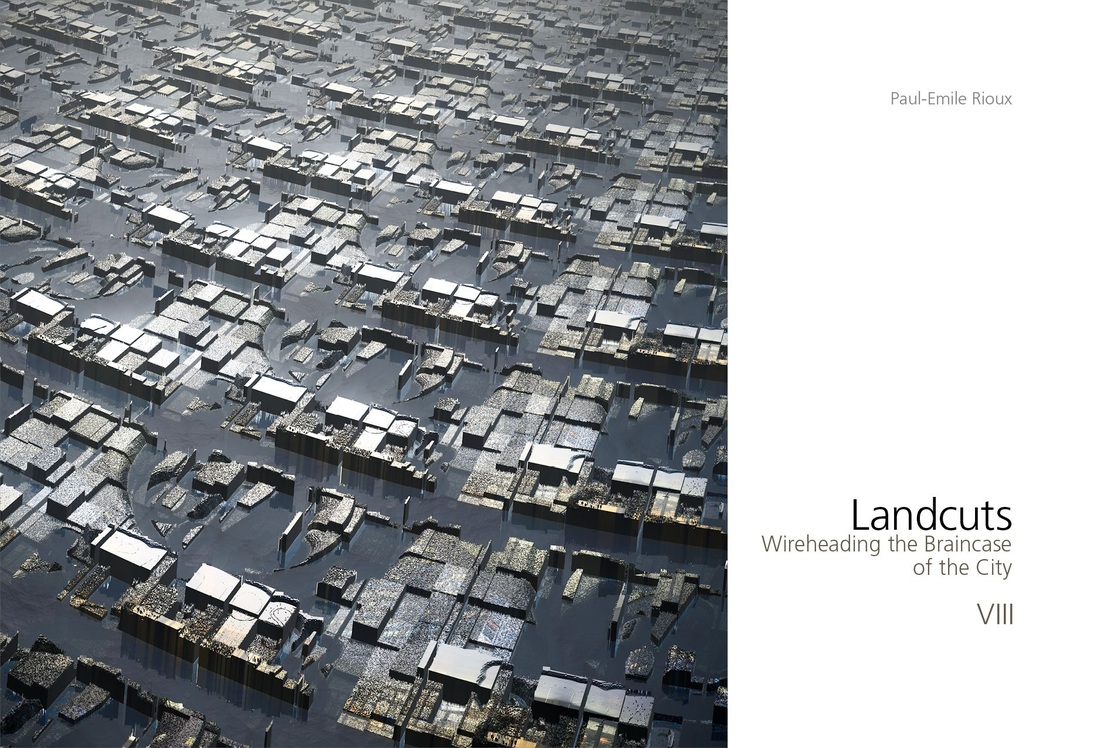

In Rioux’s work, the neural net, the synaptic endzone, if you will, is figured as optic cables that symbolize the plumbing of the city and its braincase electrical currents at one and the same time.

|

|

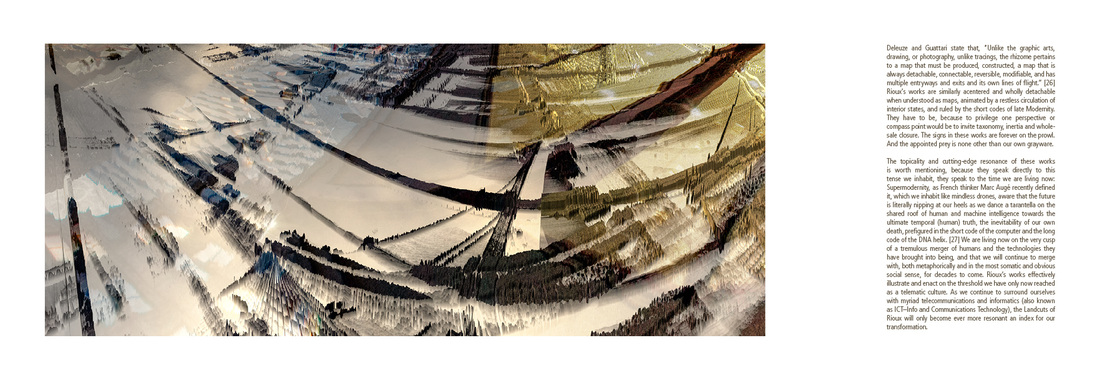

I like to think of Rioux’s prolific cityscapes as Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS or “complexity science”) that are infective, prolific and wired for pure teleologies and not abbreviated shelf-life. The three letters in the designation each contribute significantly to the definition. “Complex” connotes diversity—a multiplicity of connections between a wide variety of elements. “Adaptive” indicates an innate capacity to alter or change. A “System” is a set of connected or interdependent things or “agents.” The latter may be a person, an amoeboid, a species, a medley of anthropomorphic signs or the elements in a syntagmatic language. These “agents” act according to their assimilation of local epistemologies and conditions. Human organisms, stock markets, forest ecosystems, manufacturing businesses, biolabs, immune systems and quarantine wards—these are all examples of CAS. Why not made environments like Rioux’s as well? Rioux refuses the casual authority of the hand of the One in favor of the informational needs of the Many. Everything, for him, is relatable—and interrelated and symbiotic and true. This is why he begins a given work almost at random, and proceeds to build accordingly. He does not privilege any one station-point, and there is no formula, plan, or schedule. A Landcut has its own uterine itinerary and life cycle, he seems to say, and once he has set it on its way, it morphs according to local conditions and its own needs. It is its own umbilical tambourine.

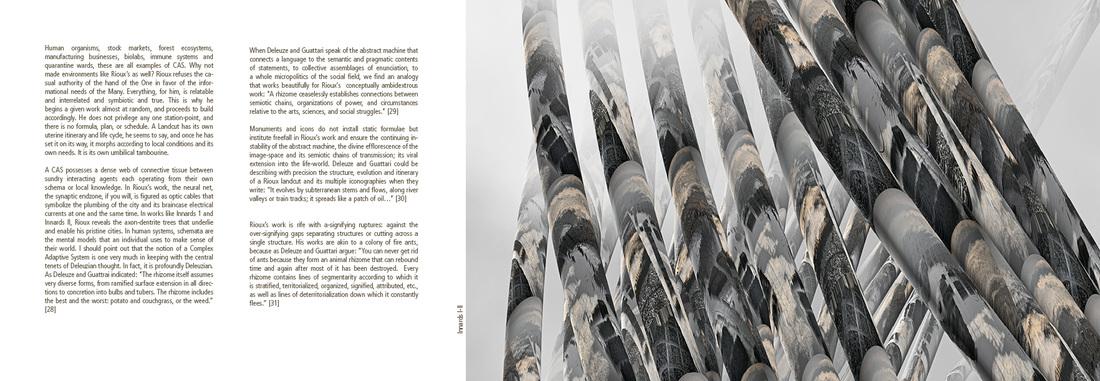

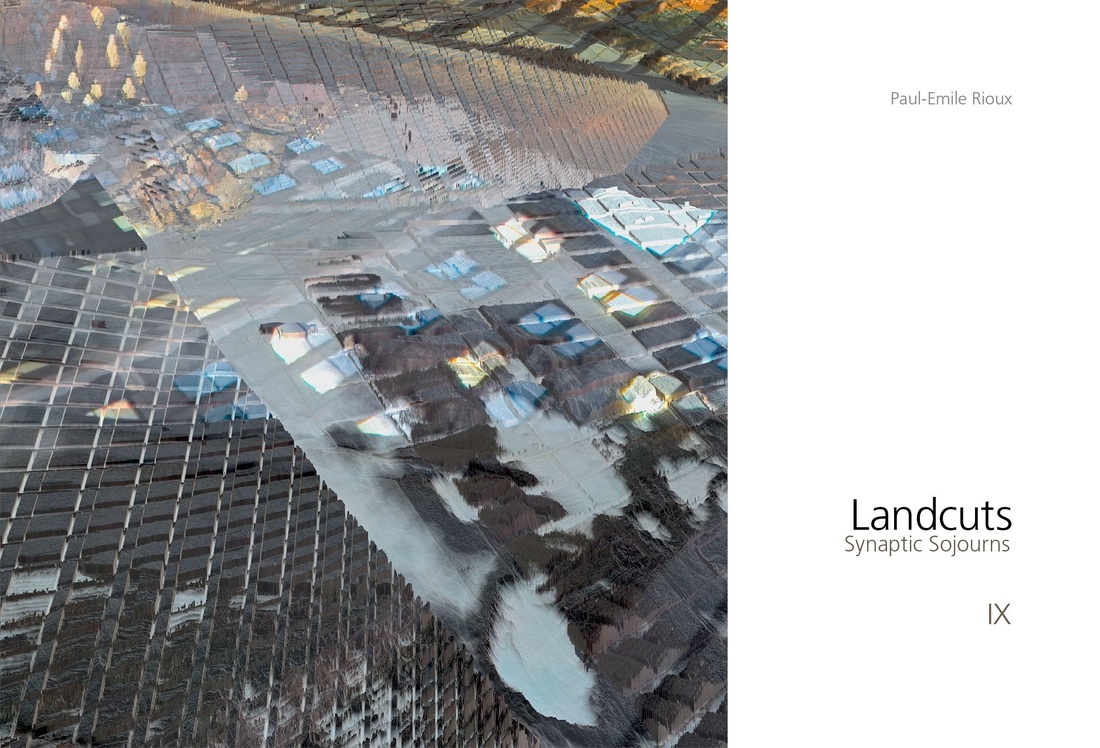

A CAS possesses a dense web of connective tissue between sundry interacting agents each operating from their own schema or local knowledge. In Rioux’s work, the neural net, the synaptic endzone, if you will, is figured as optic cables that symbolize the plumbing of the city and its braincase electrical currents at one and the same time. In works like Innards 1 and Innards II, Rioux reveals the axon-dentrite trees that underlie and enable his pristine cities. In human systems, schemata are the mental models that an individual uses to make sense of their world. I should point out that the notion of a Complex Adaptive System is one very much in keeping with the central tenets of Deleuzian thought. In fact, it is profoundly Deleuzian. As Deleuze and Guattrai indicated: “The rhizome itself assumes very diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion into bulbs and tubers. The rhizome includes the best and the worst: potato and couchgrass, or the weed.” [28] When Deleuze and Guattari speak of the abstract machine that connects a language to the semantic and pragmatic contents of statements, to collective assemblages of enunciation, to a whole micropolitics of the social field, we find an analogy that works beautifully for Rioux’s conceptually ambidextrous work: “A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.” [29] |

|

Rioux reveals the axon-dentrite trees that underlie and enable his pristine cities.

|

|

Monuments and icons do not install static formulae but institute freefall in Rioux’s work and ensure the continuing instability of the abstract machine—the divine efflorescence of the image-space and its semiotic chains of transmission; its viral extension into the life-world. Deleuze and Guattari could be describing with precision the structure, evolution and itinerary of a Rioux landcut and its multiple iconographies when they write: “It evolves by subterranean stems and flows, along river valleys or train tracks; it spreads like a patch of oil…” [30] Rioux’s work is rife with a-signifying ruptures: against the over-signifying gaps separating structures or cutting across a single structure. His works are akin to a colony of fire ants, because as Deleuze and Guattari argue: “You can never get rid of ants because they form an animal rhizome that can rebound time and again after most of it has been destroyed. Every rhizome contains lines of segmentarity according to which it is stratified, territorialized, organized, signified, attributed, etc., as well as lines of deterritorialization down which it constantly flees.” [31]

Rioux has wisely heeded Deleuze and Guattari’s advice: “Make a map, not a tracing.” [32] There is no doubt that Rioux’s cities are inherently a-centered and wholly detachable cartographies, animated by a restless circulation of interior states of becoming, and ruled by the short codes of critical late Modernity. The monolithic integers in these works are forever on the move, allergic to stasis and the status quo, and are remarkably close to rhizomes in the sense that any cohering structure is a point necessarily connected to each and every other point, in which no location may become a beginning or an end, yet the whole is heterogeneous. Finally, there is the indelibly cartographic and crenellated nature of Rioux’s endlessly replicating cities. Deleuze and Guattari remind us that the rhizome is a mapping rather than a tracing: “What distinguishes the map from the tracing is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real. The map does not reproduce an unconscious closed in upon itself; it constructs the unconscious.” [34] Rioux’s landcuts are remarkably phantasmatic maps, Venus flytraps, truly Deleuzian diagrams. By dividing his spaces into immense city-like grids that bend and shimmer, and endlessly morph, Rioux invokes ambiguity and the resilient opacity of the surfaces that surround us. Notes: 25.26.28.29.30.31.32.33.34. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987] 27. Marc Augé, Non Places – Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (London, UK: Verso, 1995. |