A computer virus as a program...

Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

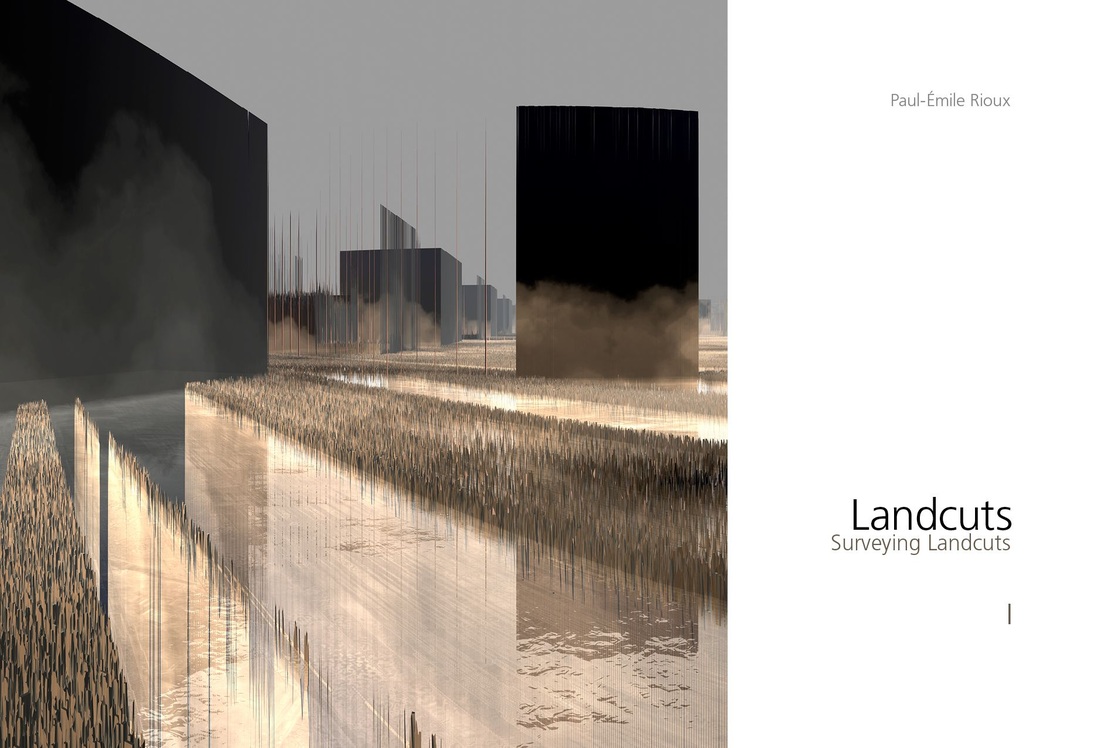

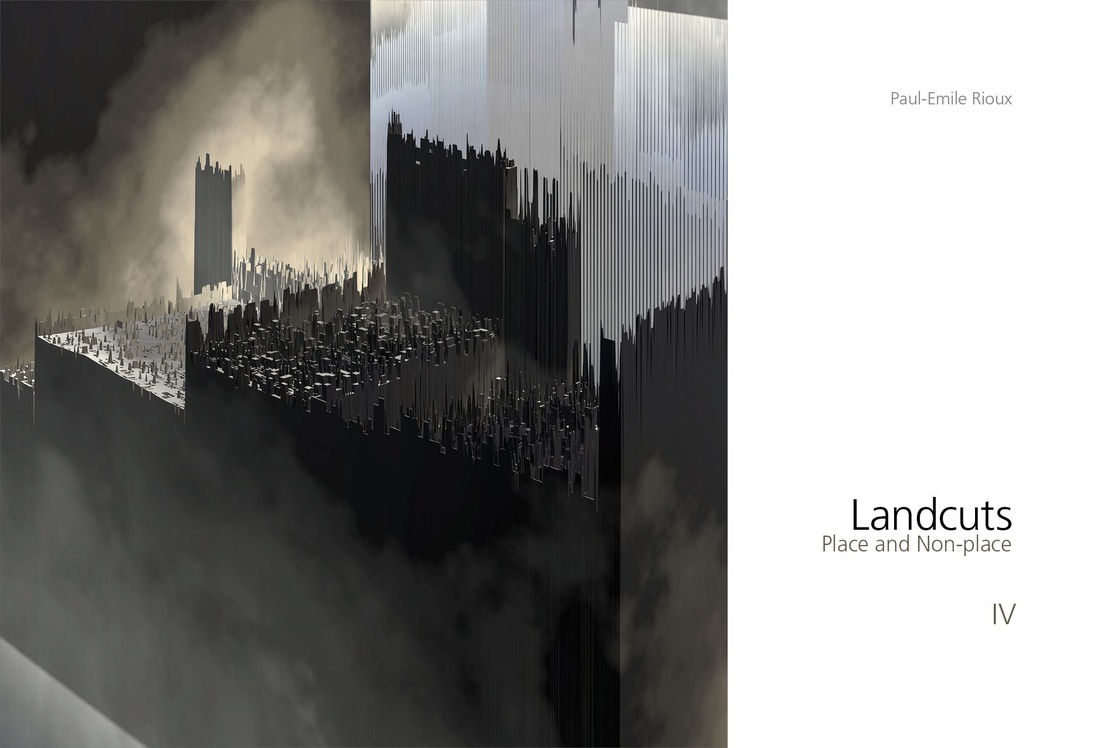

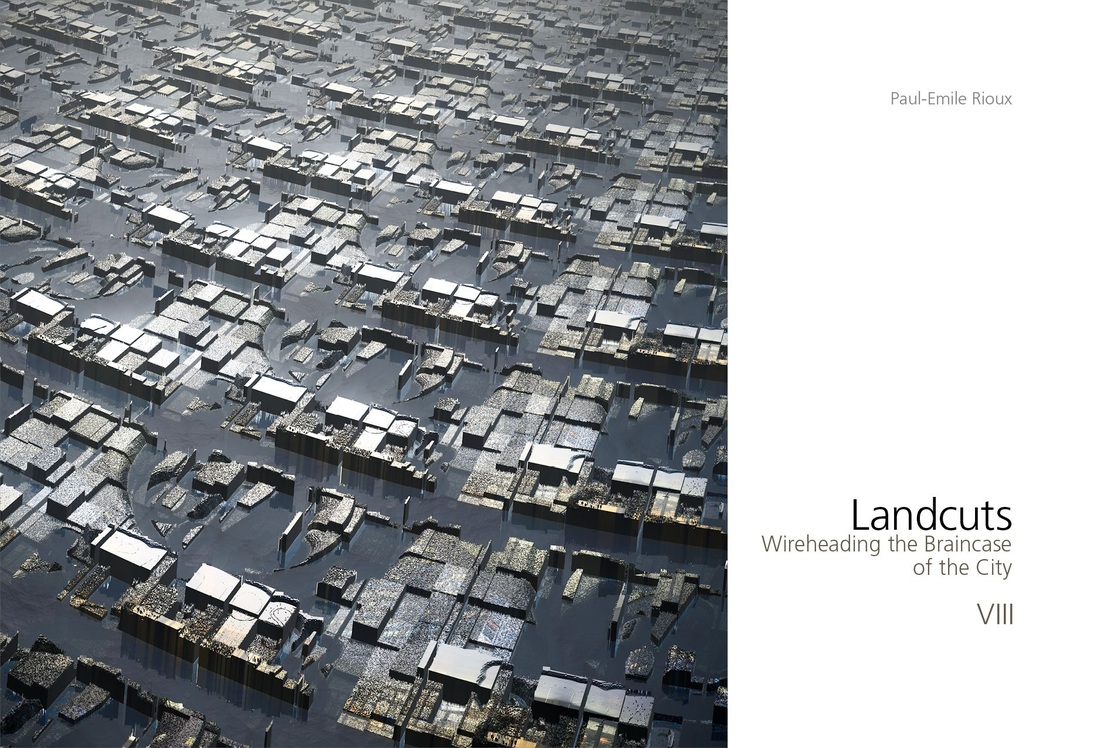

Fred Cohen authored the seminal work on computer viruses. On November 3, 1983, he created a virus as an experiment he would present to a weekly seminar on computer security. Cohen implemented the virus on a VAX 11/750 system running Unix and demonstrated his work at the security seminar on November 10, 1983. The virus achieved growth through a new utility program called "vd"—one that displayed Unix file structures graphically—but executed viral codes before performing its advertised function. These self-replicating programs segue with Rioux’s work but without the downside. One could argue that the structures that replicate in his Landcuts are viral in nature—or that the replicating virus is a stunning analogy for what they are.

Cohen defined a computer virus as a program that "infects" other programs by modifying them so as to include an updated copy of its own program. The monolithic integers in Rioux’s works could be construed as such, given their similitude and difference, and as perfect carriers for the viral infection of information |

|

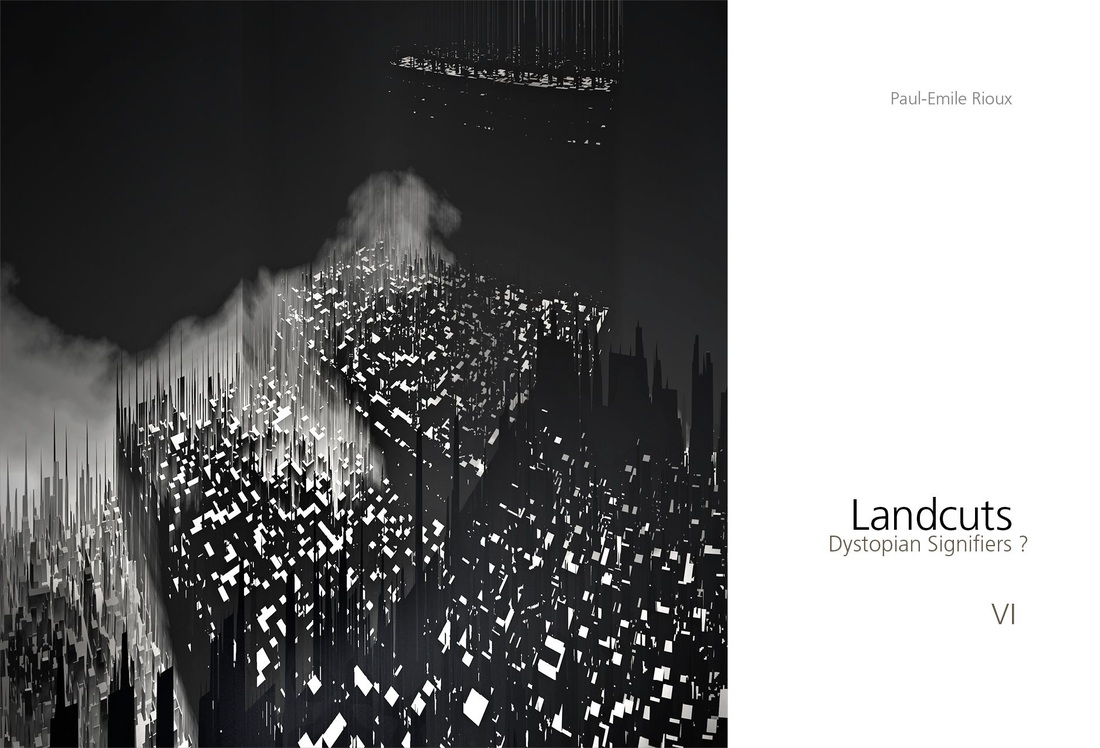

The computer virus possesses a kind of alien otherness much like the multiplying integers in Rioux’s Landcuts—an endless array of empaphoric entities, once again the black monolith from the Kubrick 2001: A Space Odyssey film.

|

|

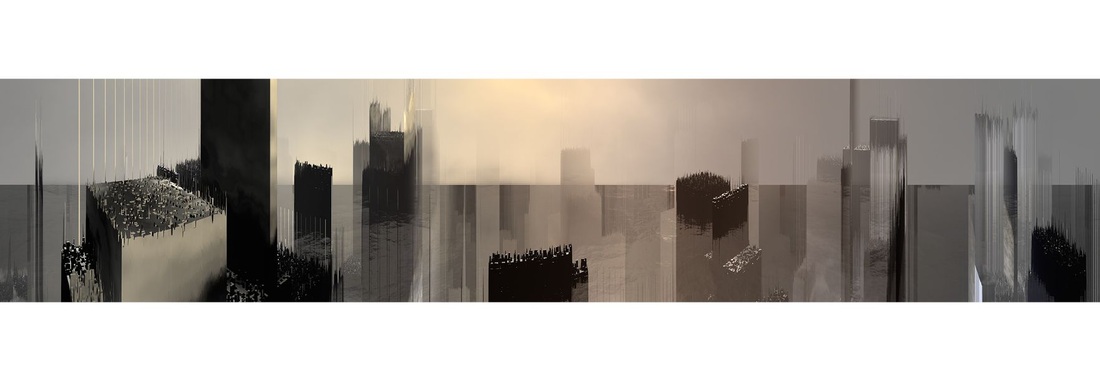

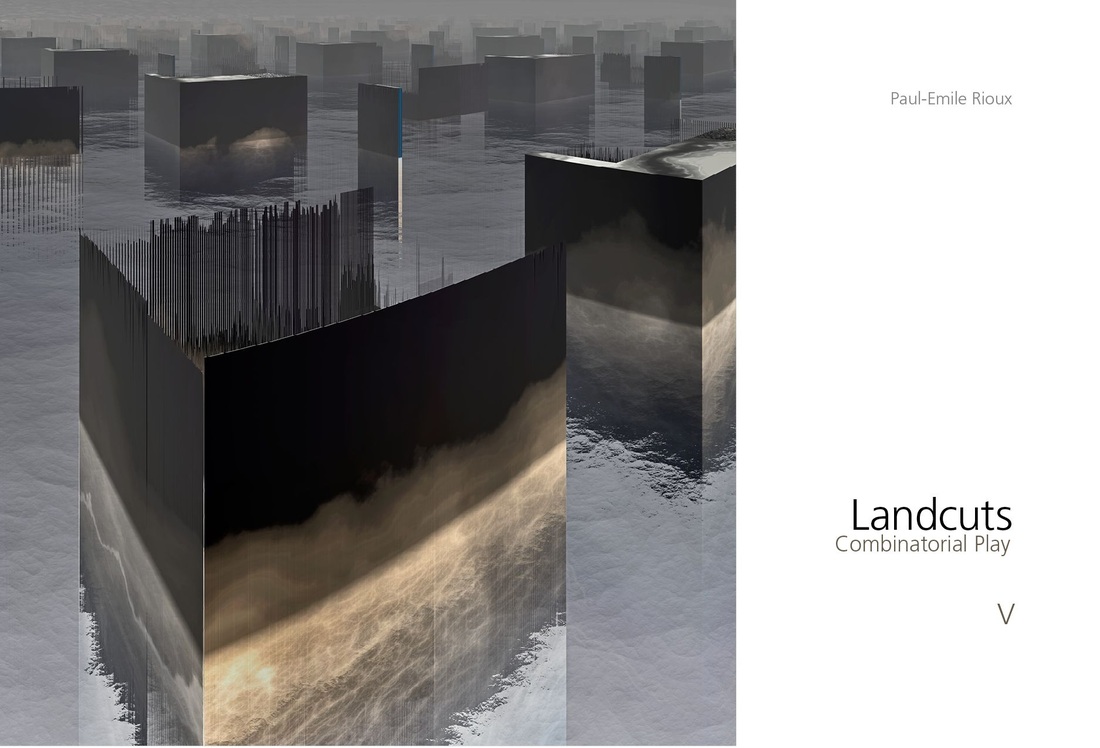

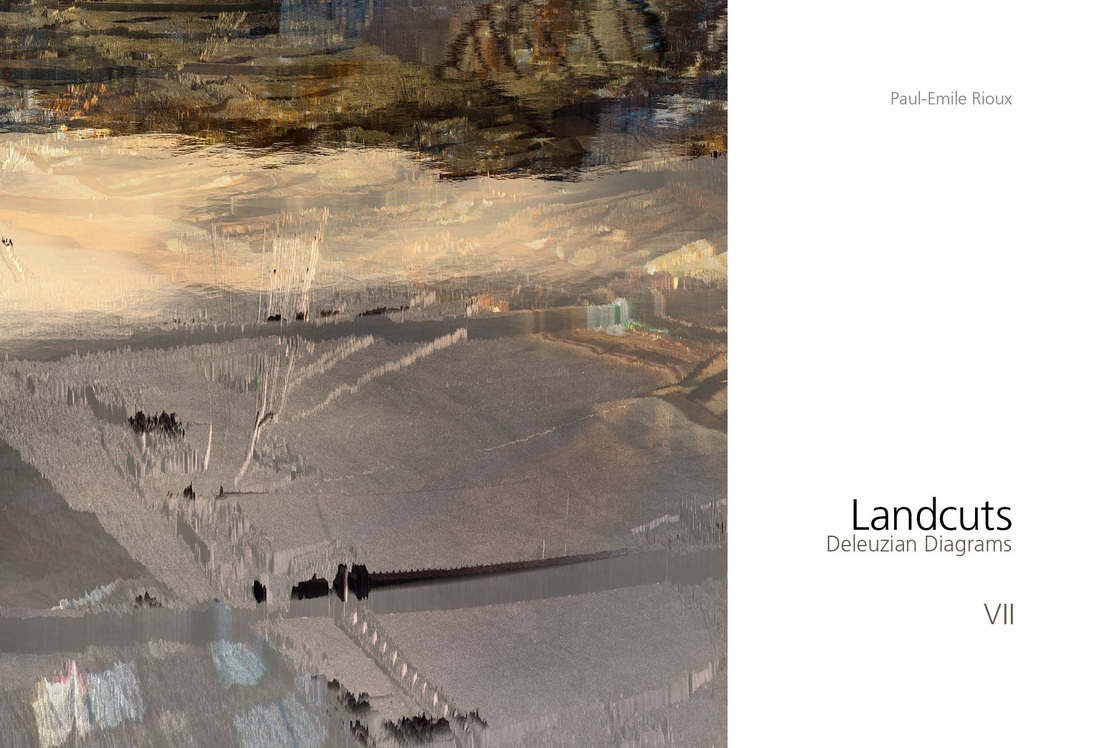

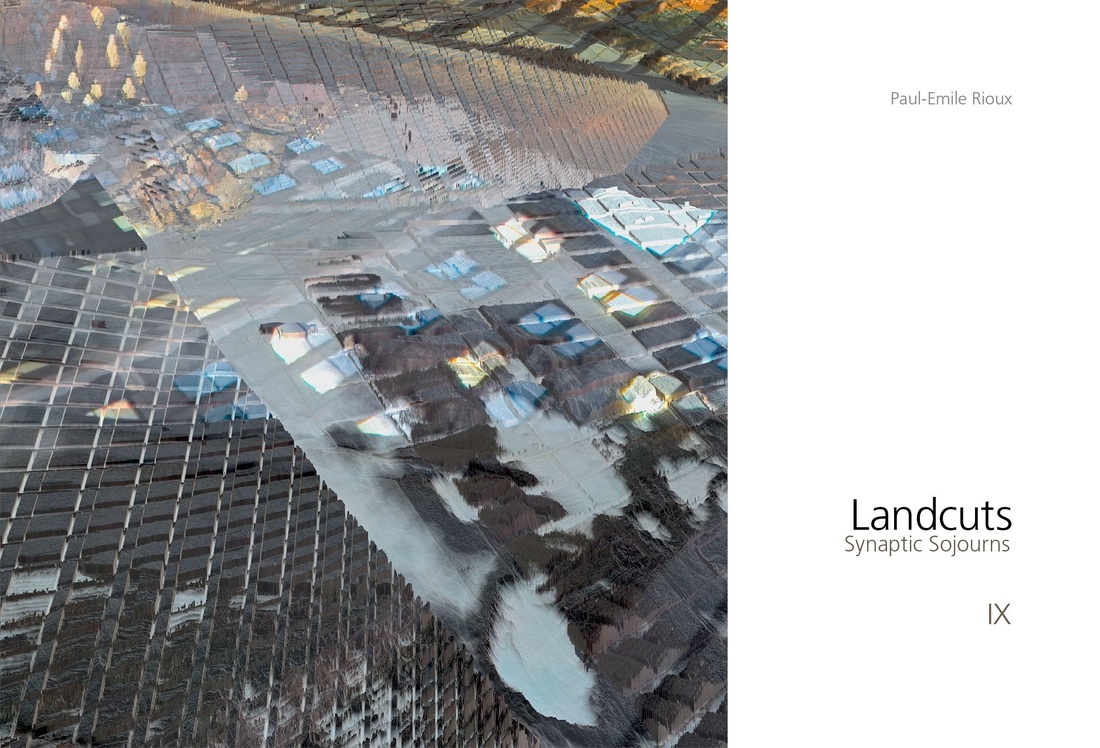

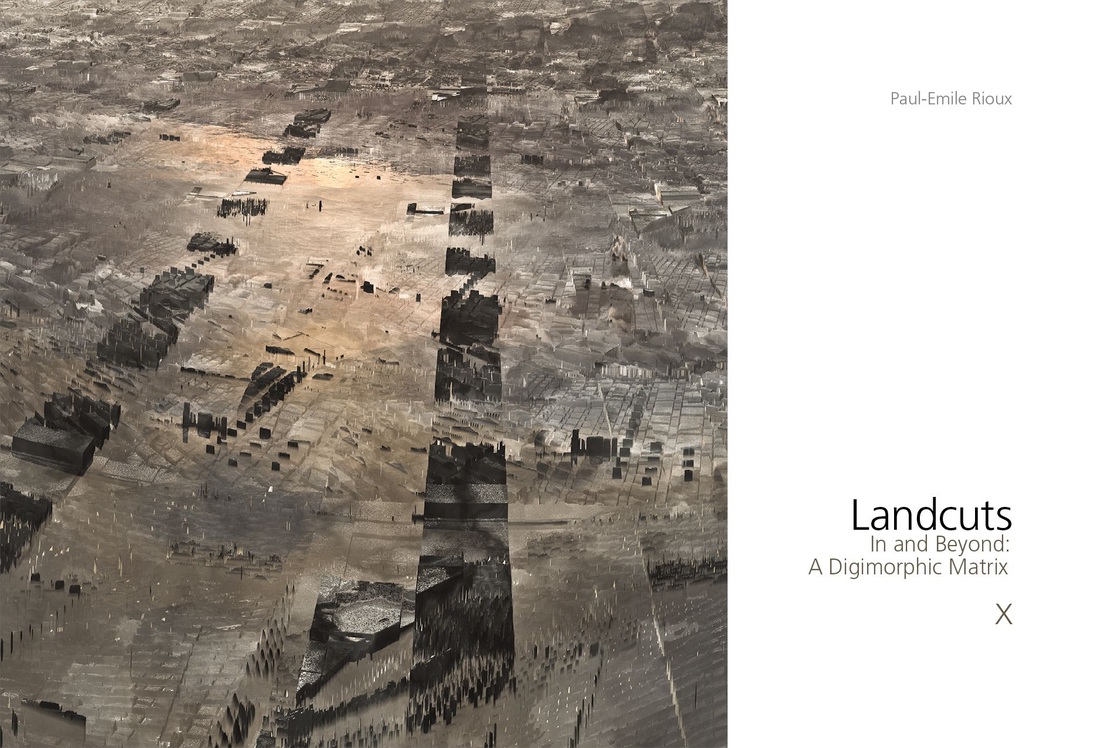

Tony Sampson has argued that the openness of the information space is nothing new in terms of the free flow of information. [7] It is now a truism that the transitive and nonlinear configuration of data flow has ushered in the accelerated sharing of code. The openness of the info-space encourages a free distribution model, and the virus has, as IBM researcher Sarah Gordon further points out, exposed the info-space as the “perfect medium” for viral infection. One can interpret Rioux’s cities as potent surrogates for a viral code that acts as an acentered Deleuzian rhizome. The downtown core is akin to an advanced polymorphic virus and, more importantly, emblemizes the ethic of open culture. If Rioux’s cities are, however, a “friendly contagion,” they also, as we shall see, embody pure vertigo.

Sean Cubitt, a prophetic voice in digital aesthetics, construes the virus as a contradictory cultural element, and substitutes the concept of information with the space of representation, thereby elevating the virus from the empirical level to that of a higher linguistic construct of reality. [8] As Sampson argues, the contagious and invasive properties of a biological parasite are metaphorically transferred to a viral technology. [9] The computer virus possesses a kind of alien otherness much like the multiplying integers in Rioux’s Landcuts—an endless array of empaphoric entities, once again the black monolith from the Kubrick 2001: A Space Odyssey film. Like Cohen, Cubitt concludes that the virus will always exist if the paths of sharing remain open to information flow. “Somehow,” Cubitt argues, “the net must be managed in such a way as to be both open and closed. Therefore, openness is obligatory and although, from the point of view of the administrator, it is a recipe for ‘anarchy, for chaos, for breakdown, for abjection,’ the ‘closure’ of the network, despite eradicating the virus, means that no benefits can accrue.” [10] Rioux’s cities are always porous, products of their own amplitude, open to the infinite. |

|

Rioux cityscape is like an anarchic/anamorphic/semaphoric virus with no apparent control centre or central agency but an infinite network of automata that freely channels information from one sector to another without hindrance.

|

|

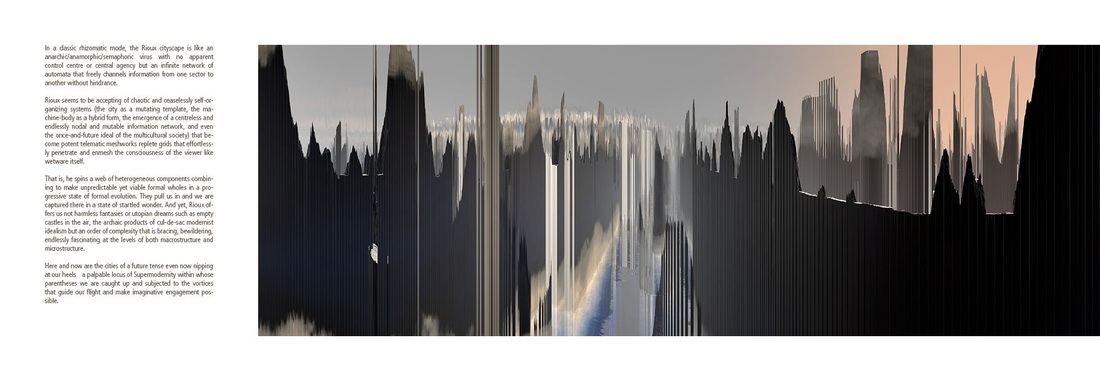

In a classic rhizomatic mode, the Rioux cityscape is like an anarchic/anamorphic/semaphoric virus with no apparent control centre or central agency but an infinite network of automata that freely channels information from one sector to another without hindrance. Rioux seems to be accepting of chaotic and ceaselessly self-organizing systems (the city as a mutating template, the machine-body as a hybrid form, the emergence of a centreless and endlessly nodal and mutable information network, and even the once-and-future ideal of the multicultural society) that become potent telematic meshworks—replete grids that effortlessly penetrate and enmesh the consciousness of the viewer like wetware itself. That is, he spins a web of heterogeneous components combining to make unpredictable yet viable formal wholes in a progressive state of formal evolution. They pull us in—and we are captured there in a state of startled wonder. And yet, Rioux offers us not harmless fantasies or utopian dreams—such as empty castles in the air, the archaic products of cul-de-sac modernist idealism—but an order of complexity that is bracing, bewildering, endlessly fascinating at the levels of both macrostructure and microstructure. Here and now are the cities of a future tense even now nipping at our heels—a palpable locus of Supermodernity within whose parentheses we are caught up and subjected to the vortices that guide our flight and make imaginative engagement possible.

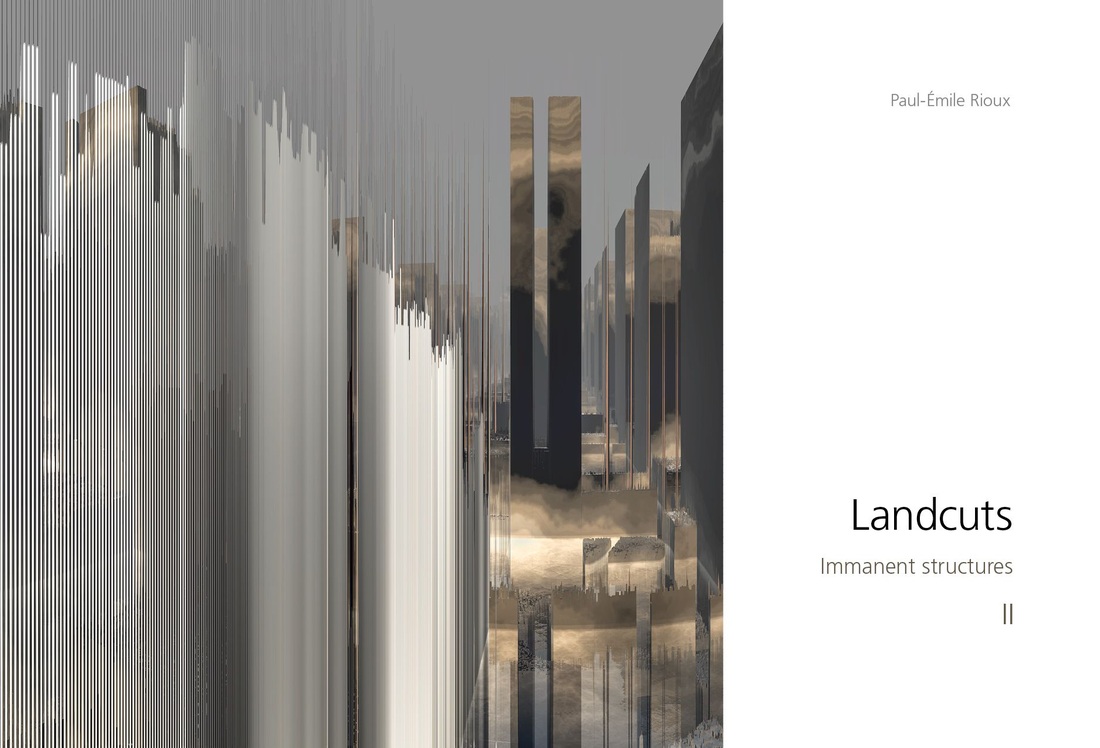

As Rioux points out, “cut” is a word that possesses replete significations, with the cinematic foremost amongst them. This artist has no interest whatsoever in collage, unlike so many of his confreres, and his manipulations seem to allow for organic, vertical growth and depth. Here, the editing of film is more apropos where a cut is a specific piece of film that corresponds to a single shot. The “final cut” is the final edit of the whole film. His are truly director’s Landcuts. But the Landcuts easily transcend cinematic meaning and explore semiotic territory through the logic of digitality. They are genetic things. No stasis here and no discernible missteps, either. His cities are rife with untold communities of signs and portents, insistent aura and vectorial alumni. These are cities splintering and proliferating at their very cores, much like language itself, where the core is never actually seen, but more precisely its radial edges and continuing tumult can be inferred everywhere. Notes; 6.7.8.9.10: Fred Cohen,1983 |