The idea of “wetware”

“Studies in human subjects with implanted electrodes have demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the depth of the brain can induce pleasurable manifestations, as evidenced by the spontaneous verbal reports of patients, their facial expression and general behavior, and their desire to repeat the experience.”

José M. R. Delgado, M.D., Physical Control of the Mind, 1969 |

Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

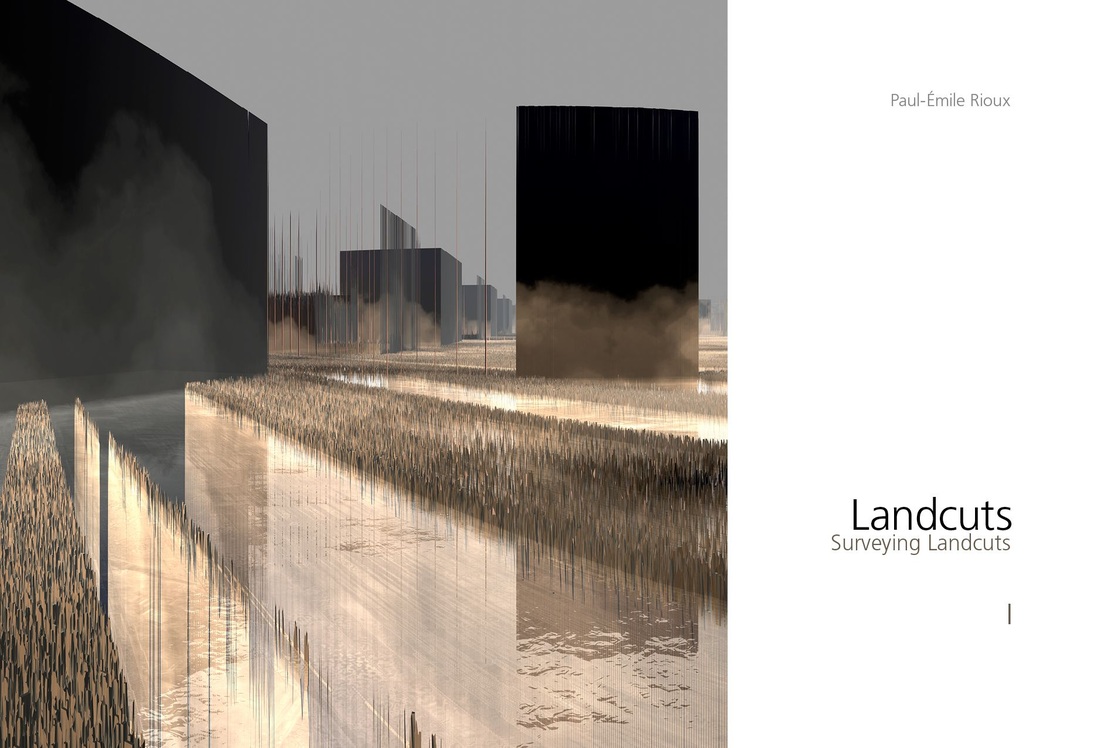

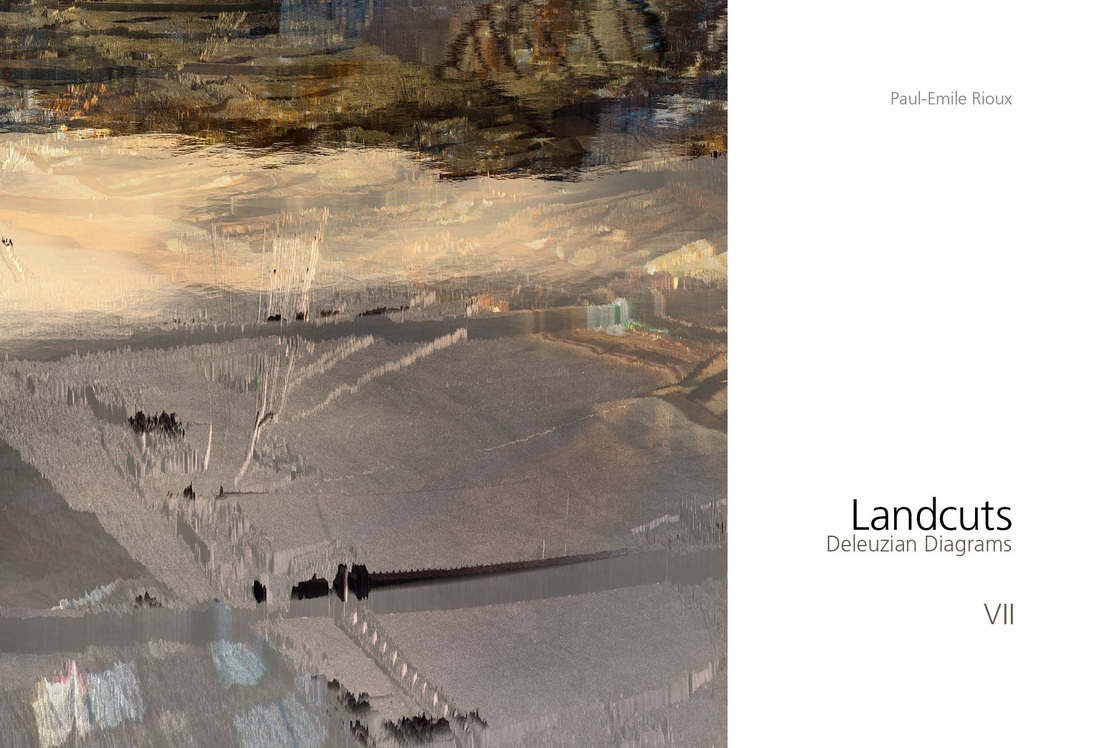

Not surprisingly, Rioux’s works reveal his longstanding interest not just in the future (as opposed to the past) tenses of photography and digital practice, but revel in the whole bio-cybernetic software of mind and the aforementioned “wetware” in particular. A technical term for the integration of the concepts of the physical reality of the central nervous system and the mental construct known as “mind,” wetware is particularly relevant to the works under discussion here.

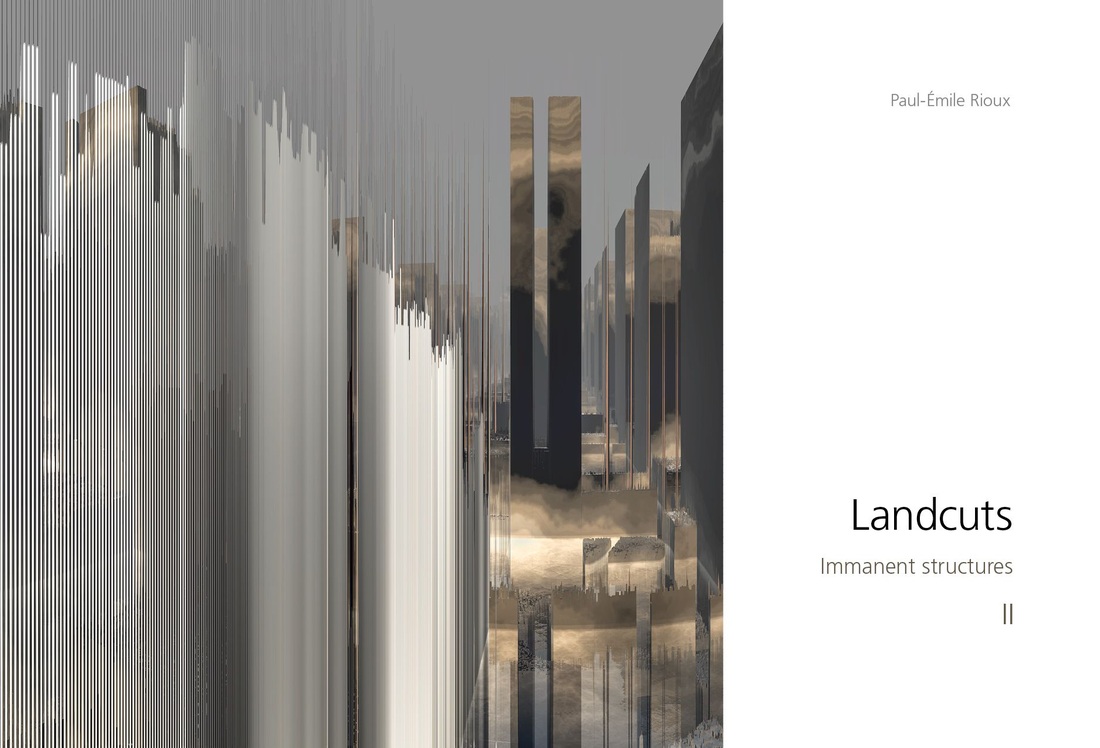

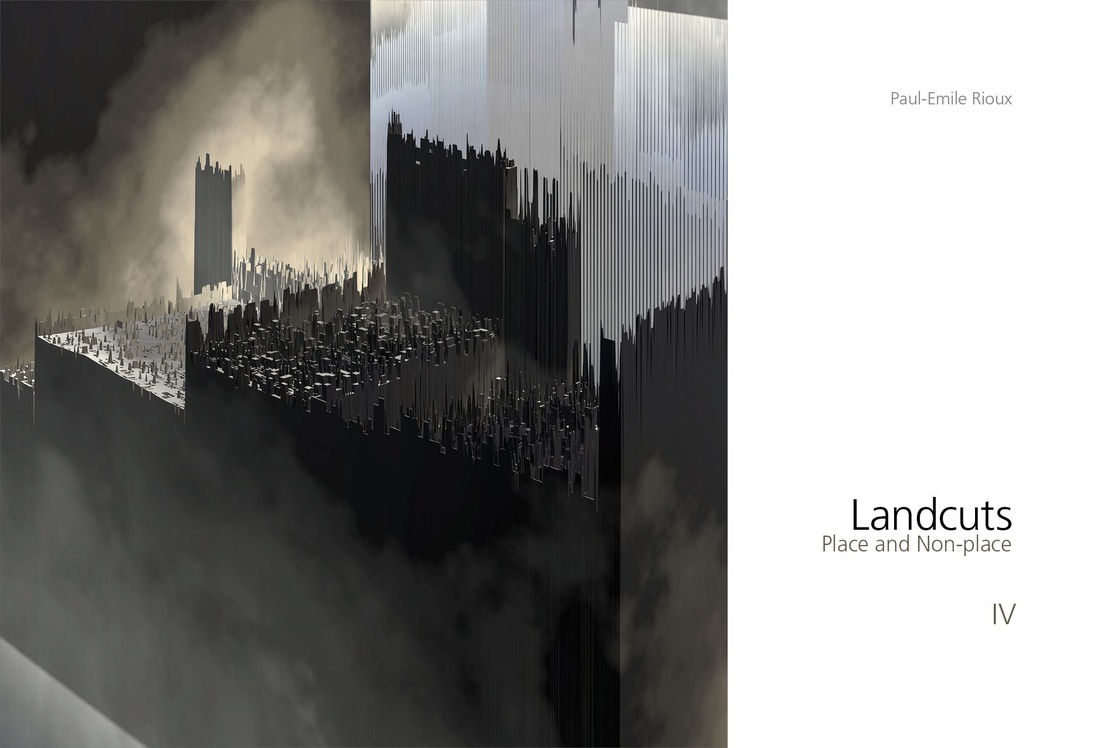

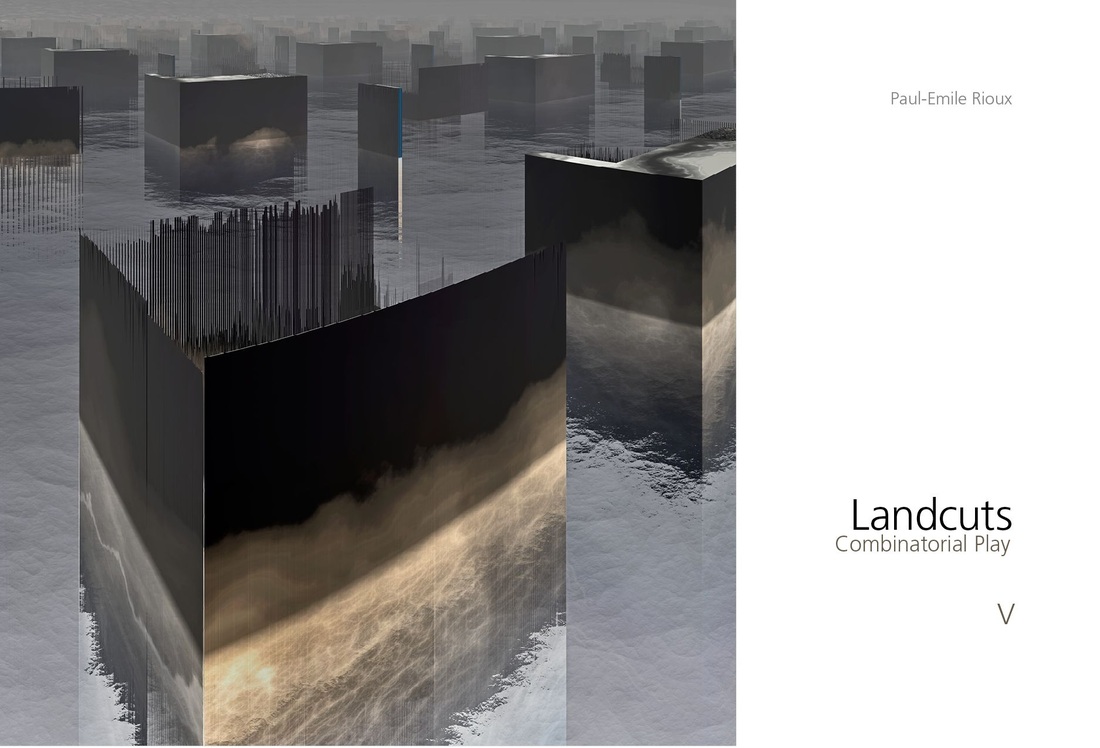

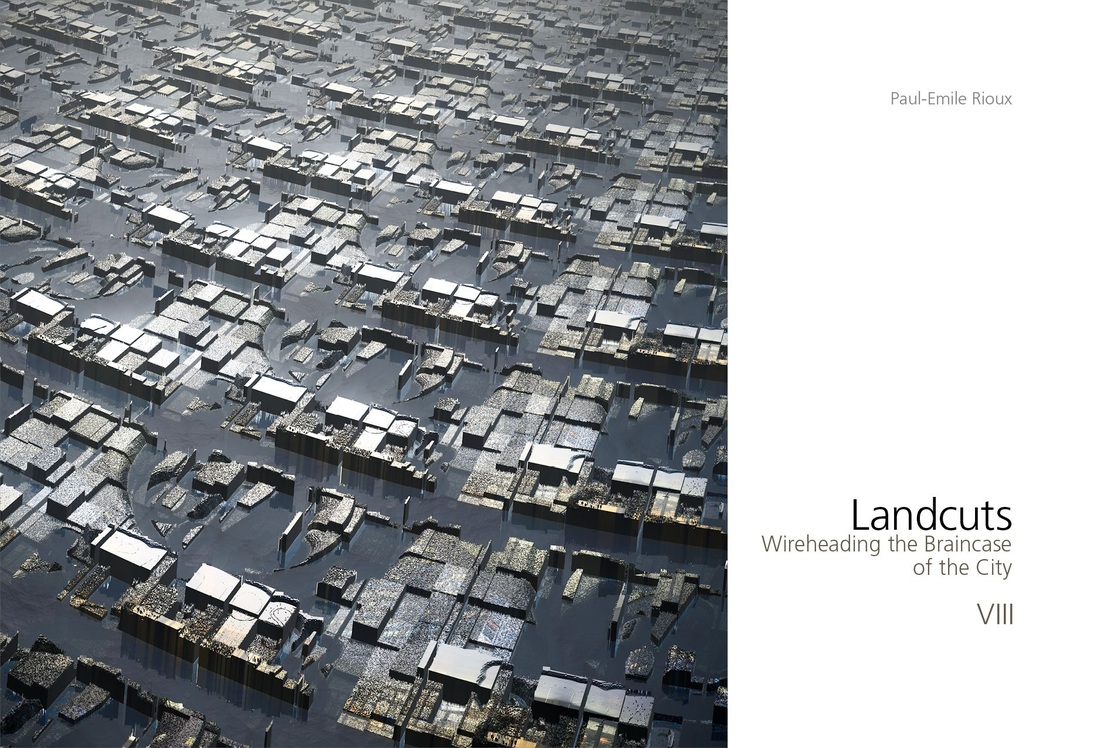

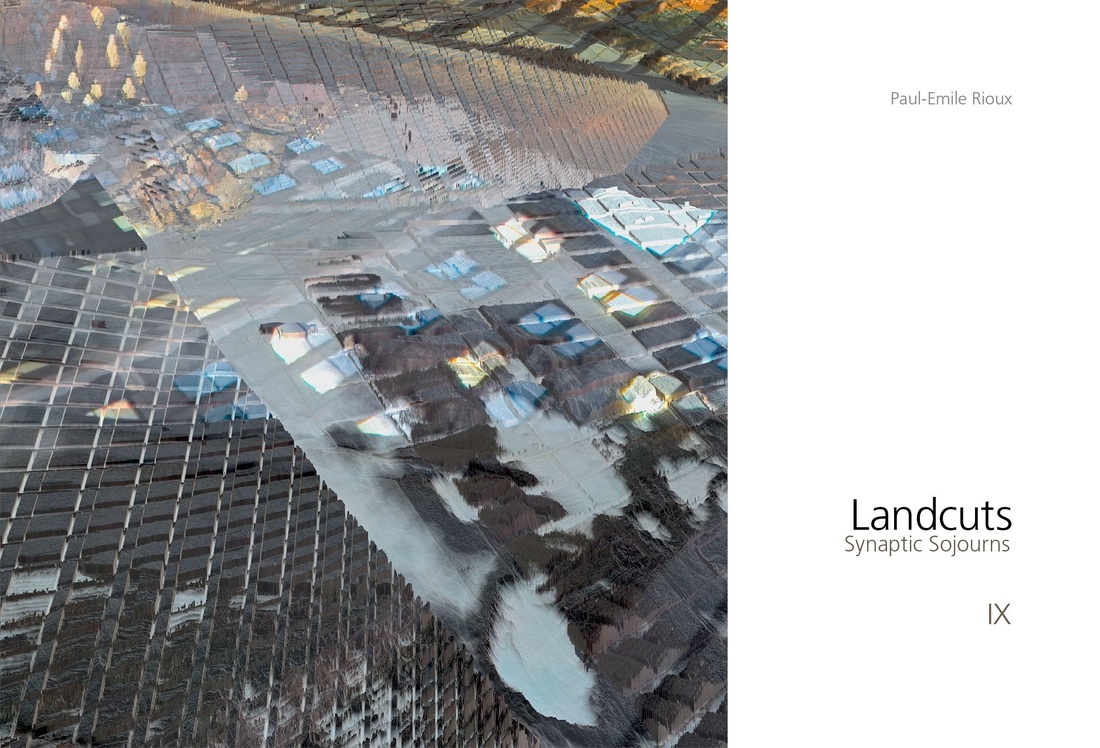

Electrically stimulating some regions (such as the mesolimbic dopamine system) results in a surfeit of pure pleasure. Similarly, the multiplication of the arcs in Rioux’s cities of the end times yield a certain rapture. If wireheading [35] and wetware have been invoked in the past principally in science-fiction media, it makes a grand, gravid and hurly-burly entrance here. And it must be said that the wealth of metaphorical wetware—and the disorderly outbursts of pure painted matter that constitute its conduit—makes for an inordinate amount of pure optic pleasure; here is the promise of a narcotic-like high, death by ecstasy, if you will. This is not just puerile hyperbole on my part, but a tribute to the power of Rioux’s polymorphous work to shed all kinds of emanations like so many synaptic sparks. They warp, morph, pervert, possibly whack (not in the heart of the art gallery but inside your very own head) and surely cyberjack, our perception. |

|

Rioux’s demanding and vertiginous works means not just coming to terms with the way we live now, but what and how we will be living the day after tomorrow.

|

|

Specifically, the more pressing incarnation of the idea of “wetware” in science fiction in terms of computer interface and the cybernetic augmentation to human beings, as in the novels of William Gibson, Rudy Rucker and others, is like a proverbial engram, walk-through or operating manual for the assimilation of these abstractions. Making sense of Rioux’s demanding and vertiginous works means not just coming to terms with the way we live now, but what and how we will be living the day after tomorrow.

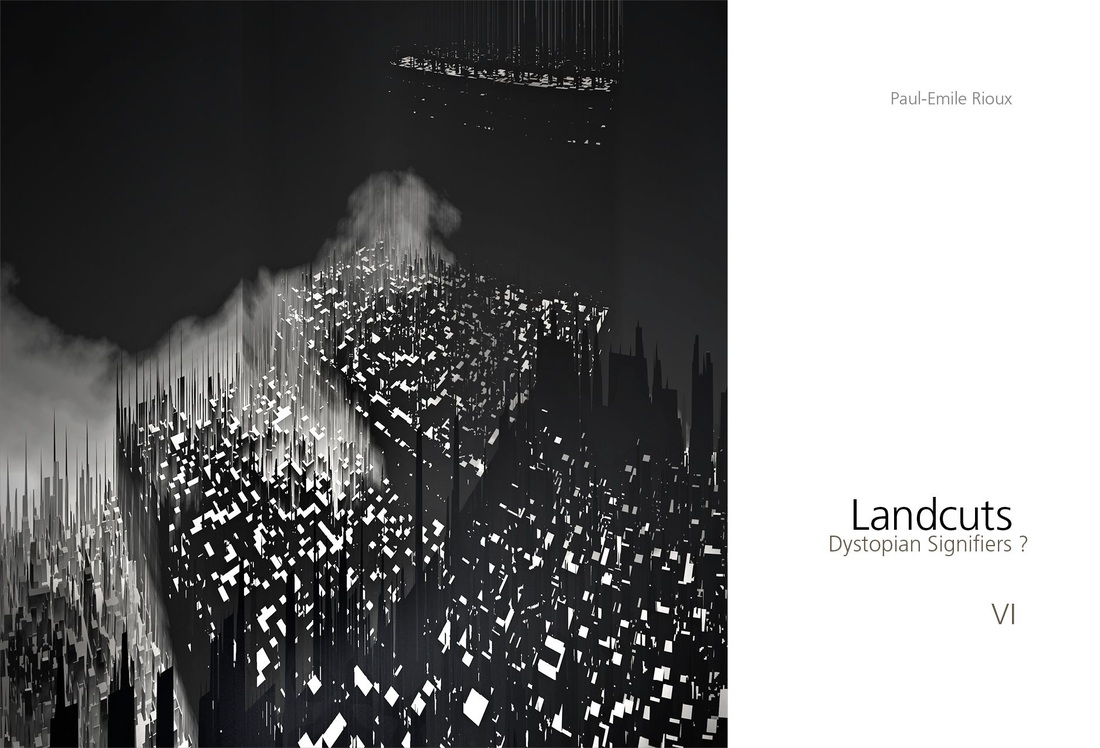

They snake their way inside our heads, after all, as though directly plugged into a receptacle at the base of the neck—whether or not we have a plug-in back there, or are otherwise wetwired, wireheaded or merely prosthetically enhanced—and then take a few ungainly detours through our gray matter. It doesn’t matter. Imagination is its own plug-in, after all. Here, painted marks are like loaded impulses traveling at breakneck speed through the maze of the human corpus calossum, through constantly morphing physical connections, and an atmospheric haze of chemical and electrical hail raining down across huge relatable gaps, and across the spans of lightning-like bridges of input connections there that just as often fail and fall, and are endlessly being rebuilt. This frenzied form of interaction between physical and mental domains—which takes its cue from the central region of tissue in the human brain which passes “messages” between left and right hemispheres—requires a new term that radically exceeds the definition of both software and hardware: I mean, of course, the aforementioned wetware. Wetware is now a ubiquitous term that is used when referencing human subjects (programmers, operators, administrators) working in ergonomic synchronicity with computer systems. In the communities of global USENET, hacker culture and elsewhere, wetware is also known as “liveware,” “meatware” or the acronym PEBKAC (Problem Exists Between Keyboard And Chair). (Interestingly, a wetware-related problem is often used in these same communities as a synonym for user error. If we err in our understanding of the implications of Rioux’s prophetic work here, it only shows our own wetware is clearly in need of an upgrade.) |

|

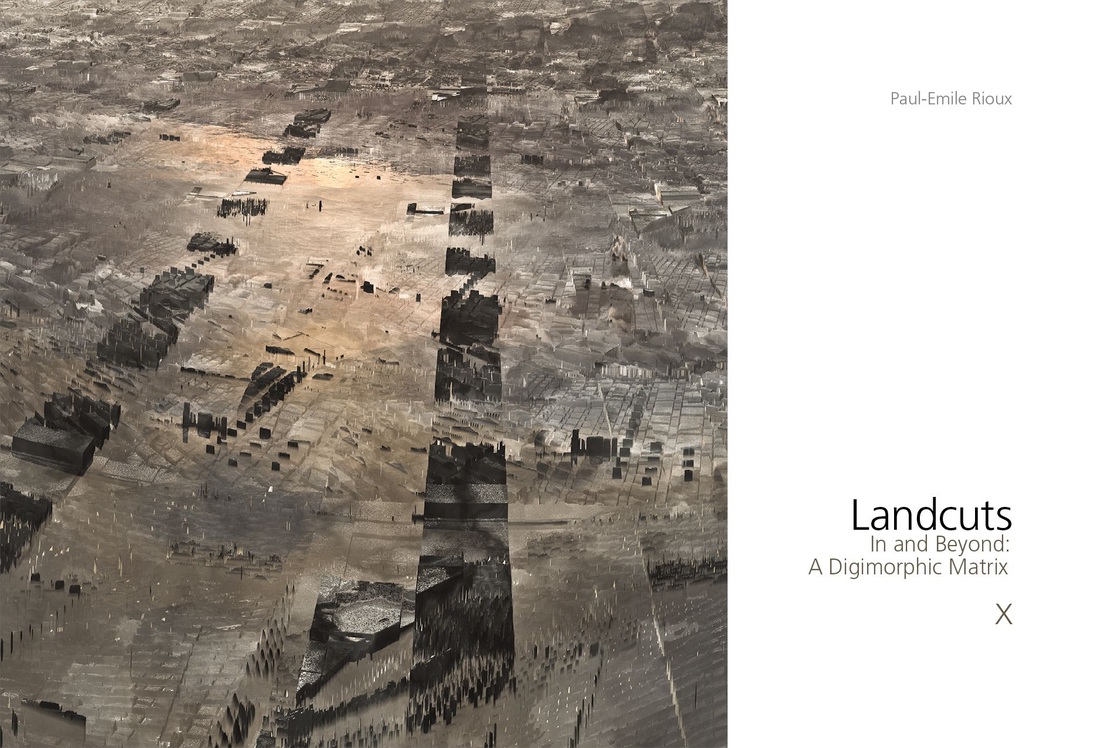

Rioux’s works effortlessly cross over into a strikingly contemporaneous and equally cutting-edge mindset. Why? Because he wants his work to act like the stealthiest of pathogens—and his dark, edgy and even dirty iconographic patois imbues them with that damaged heart like venomous snakes loosed on a plane in flight.

|

|

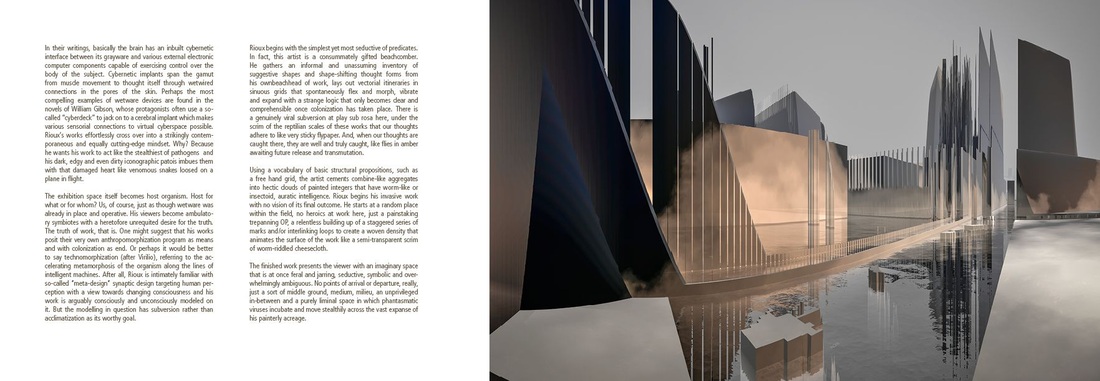

Throughout his remarkable Ware Tetralogy, Rudy Rucker uses wetware as synonymous with the underlying program of any identifiably biological system. While Rucker does not himself employ his term wetware in the sense of cybernetic augmentation, other writers such as William Gibson, Peter F. Hamilton and Richard K. Morgan, have and do. In their writings, basically the brain has an inbuilt cybernetic interface between its grayware and various external electronic computer components capable of exercising control over the body of the subject. Cybernetic implants span the gamut from muscle movement to thought itself through wetwired connections in the pores of the skin. Perhaps the most compelling examples of wetware devices are found in the novels of William Gibson, whose protagonists often use a so-called “cyberdeck” to jack on to a cerebral implant which makes various sensorial connections to virtual cyberspace possible. Rioux’s works effortlessly cross over into a strikingly contemporaneous and equally cutting-edge mindset. Why? Because he wants his work to act like the stealthiest of pathogens—and his dark, edgy and even dirty iconographic patois imbues them with that damaged heart like venomous snakes loosed on a plane in flight. The exhibition space itself becomes host organism. Host for what or for whom? Us, of course, just as though wetware was already in place and operative. His viewers become ambulatory symbiotes with a heretofore unrequited desire for the truth. The truth of work, that is. One might suggest that his works posit their very own anthropomorphization program as means—and with colonization as end. Or perhaps it would be better to say technomorphization (after Virilio), referring to the accelerating metamorphosis of the organism along the lines of intelligent machines. After all, Rioux is intimately familiar with so-called “meta-design”—synaptic design targeting human perception with a view towards changing consciousness—and his work is arguably consciously and unconsciously modeled on it. But the modelling in question has subversion rather than acclimatization as its worthy goal.

Rioux begins with the simplest yet most seductive of predicates. In fact, this artist is a consummately gifted beachcomber. He gathers an informal and unassuming inventory of suggestive shapes and shape-shifting thought forms from his own beachhead of work, lays out vectorial itineraries in sinuous grids that spontaneously flex and morph, vibrate and expand with a strange logic that only becomes clear—and comprehensible—once colonization has taken place. There is a genuinely viral subversion at play sub rosa here, under the scrim of the reptilian scales of these works that our thoughts adhere to like very sticky flypaper. And, when our thoughts are caught there, they are well and truly caught, like flies in amber awaiting future release and transmutation. |

|

Fusing the technological and the biological in a single fluid frame of reference, Rioux grows his artistic language methodically.

|

|

Using a vocabulary of basic structural propositions, such as a free hand grid, the artist cements combine-like aggregates into hectic clouds of painted integers that have worm-like or insectoid, auratic intelligence. Rioux begins his invasive work with no vision of its final outcome. He starts at a random place within the field, no heroics at work here, just a painstaking trepanning OP—a relentless building up of a staggered series of marks and/or interlinking loops to create a woven density that animates the surface of the work like a semi-transparent scrim of worm-riddled cheesecloth. The finished work presents the viewer with an imaginary space that is at once feral and jarring, seductive, symbolic and overwhelmingly ambiguous. No points of arrival or departure, really, just a sort of middle ground, medium, milieu, an unprivileged in-between and a purely liminal space in which phantasmatic viruses incubate and move stealthily across the vast expanse of his painterly acreage.

Fusing the technological and the biological in a single fluid frame of reference, Rioux grows his artistic language methodically, if sometimes recklessly, while offering ample binary helpings of high-tech and organic eye candy to the viewer’s hungry, say better, well-nigh insatiable—and always, of course, narcissistic optic. Notes: Wireheading, a related term coined by author Larry Niven for implanting a chip in the brain that stimulates the pleasure centre on demand, yields doses of pleasure. Think of Michael Crichton’s seminal novel The Terminal Man, in which a subject who suffers from psychomotor epilepsy, has his forebrain stimulated in this manner to stave off attacks. |