Text: James D Campbell, 2014

|

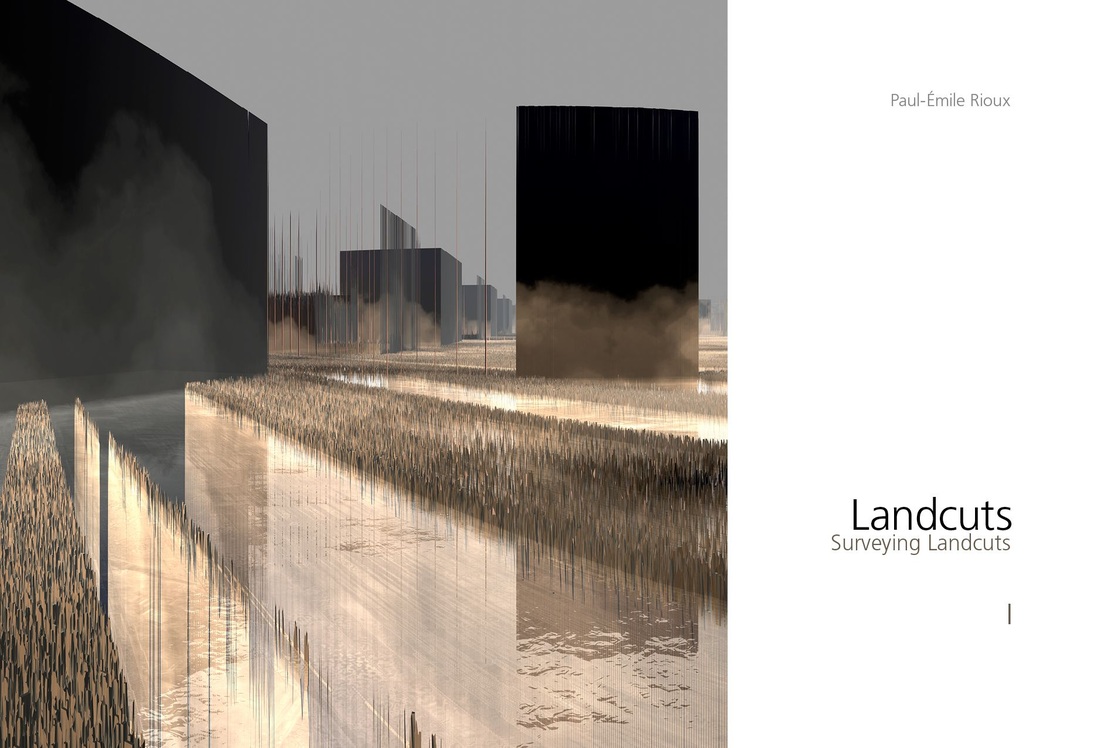

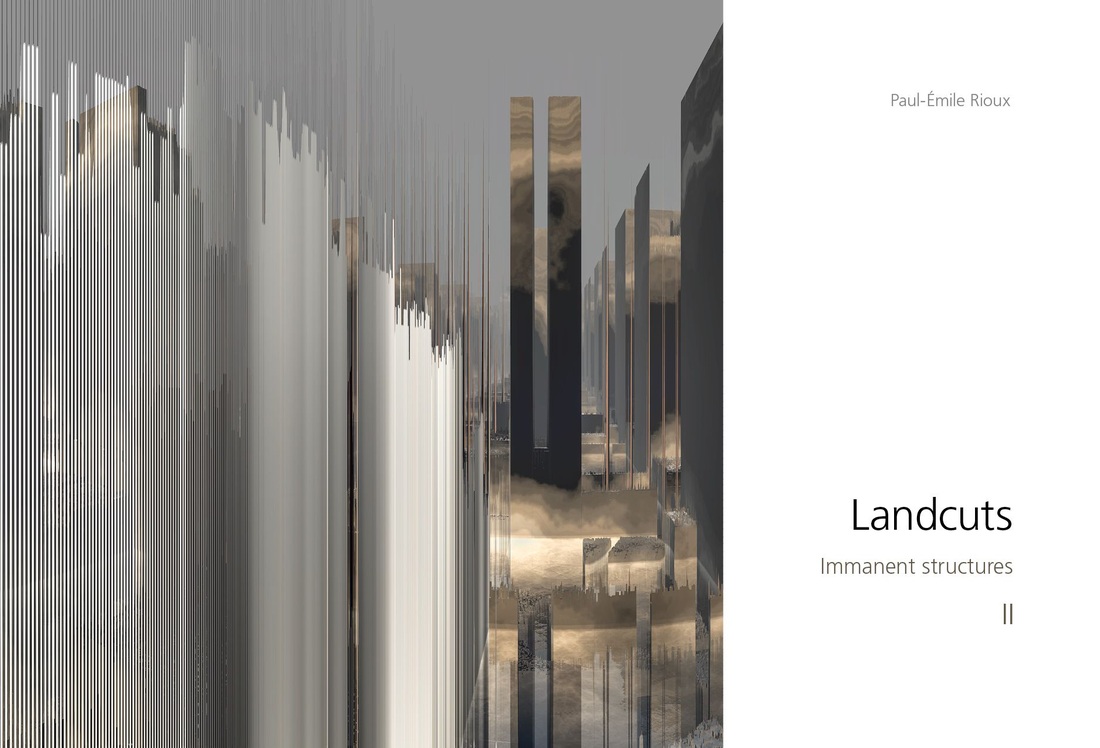

When I think of a counterpart in literature to Rioux’s strange and bracing abstracts, I don’t necessarily appeal to any of the usual suspects, or to a single great fiction of our era, but to one of the greatest reads of the twentieth century and now, unbelievably, some fifty years young. I refer to the eminent mathematician and games theory savant John von Neumann’s prophetic and still seminal The Computer and the Brain (1958). While technically unfinished, the book is satisfying and sustaining food for thought. It is also a sort of resonant narrative tract for me when I look hard at Paul-Émile Rioux’s subversive and neurally imbricated cityscapes.

|

|

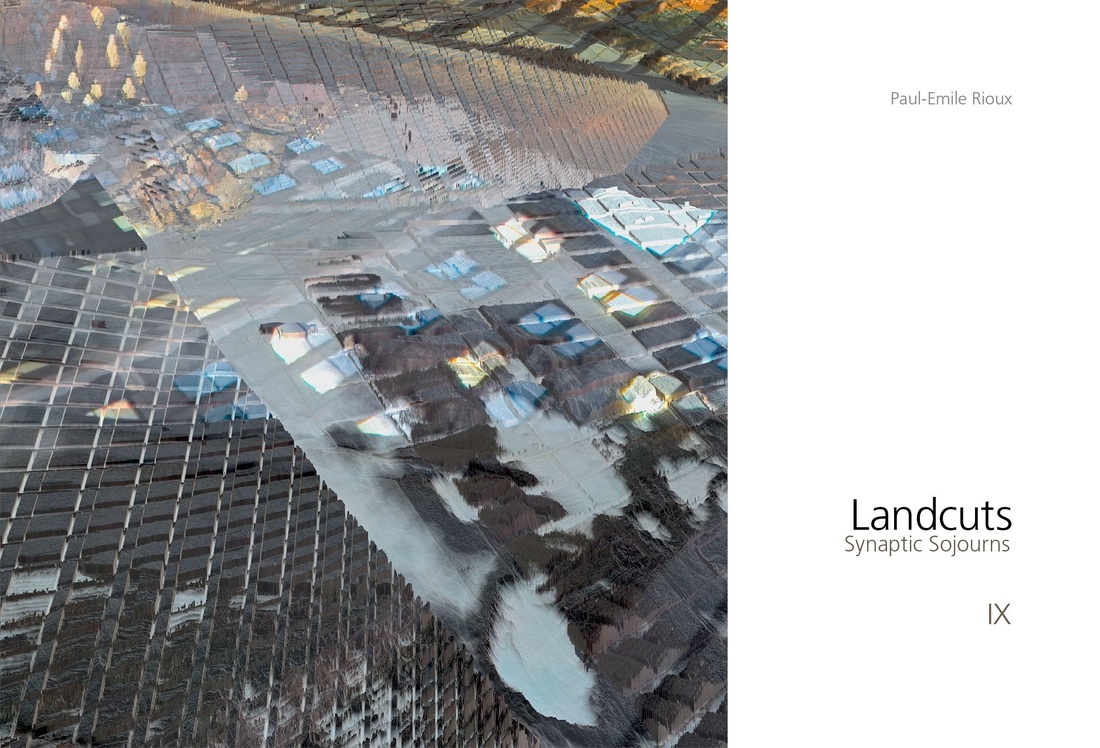

We might draw an analogy to Rioux here and suggest that his works possess complementary aspects of both the analogical and the digital.

|

|

The Computer and the Brain has a binary structure. The first part addresses the computer and the second part, the human brain. Some conclusions are offered that stem from the comparison with respect to the role of code and language. As L. Leydesdorff has pointed out, these conclusions are perhaps the most stimulating part of the book because Von Neumann addresses arresting reflexive issues, which had not previously been addressed in the cybernetic tradition. [36] Indeed, they are still provocative today, and hugely pertinent here. After baldly stating that he himself has no background in neurology or psychiatry, but is only a (humble) mathematician, just as Rioux might state that he is only an artist, not a mathematician, Von Neumann embarks upon the first part of his monograph by explaining the components of a computer in the language of and from the perspective of a computer scientist. First, he enumerates the salient differences between analog and digital computers. This series of clever distinctions will have some relevance for the discussion of the brain because—as he states in the second part—the brain can ostensibly be considered as a digital computer. However, certain elements of analog computing will also become relevant in understanding the functioning of the brain. We might draw an analogy to Rioux here and suggest that his works possess complementary aspects of both the analogical and the digital.

|

|

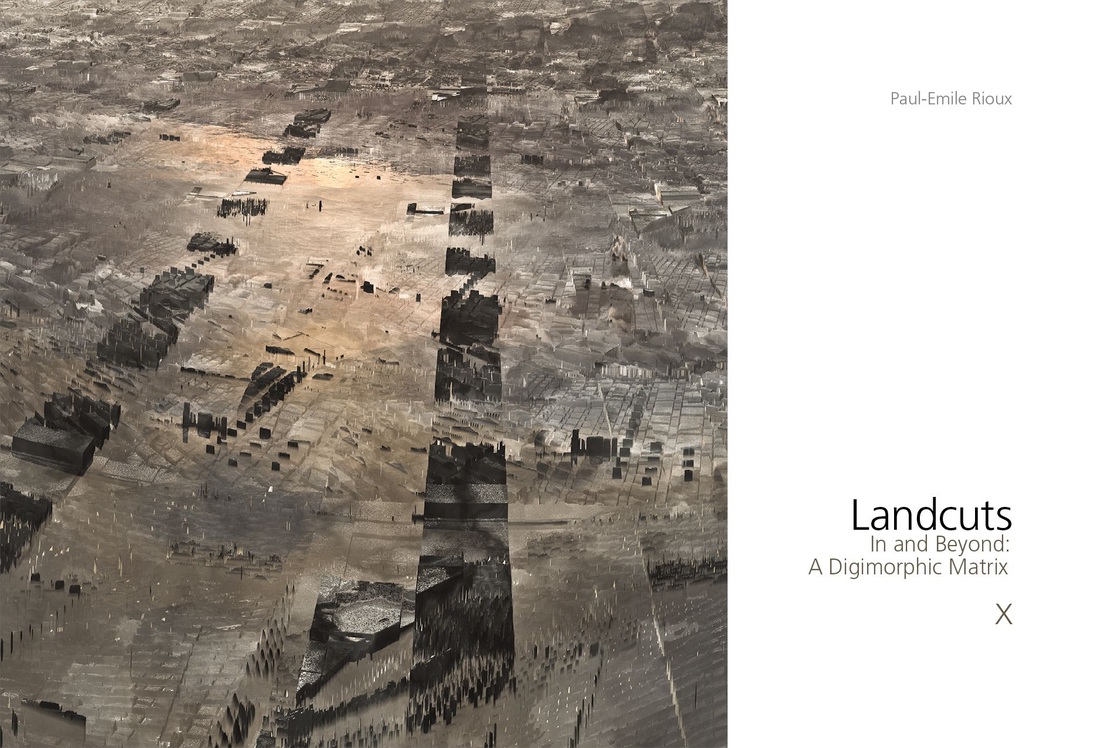

Any given work by Rioux is a sort of open-ended autopoietic system that practices a mirroring, rather than outright mimicry, of the immanent machine order and neurological becoming of the short code.

|

|

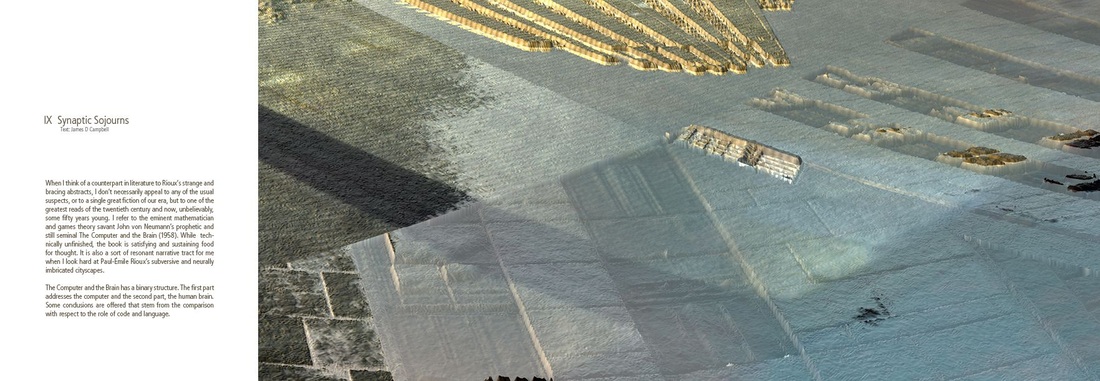

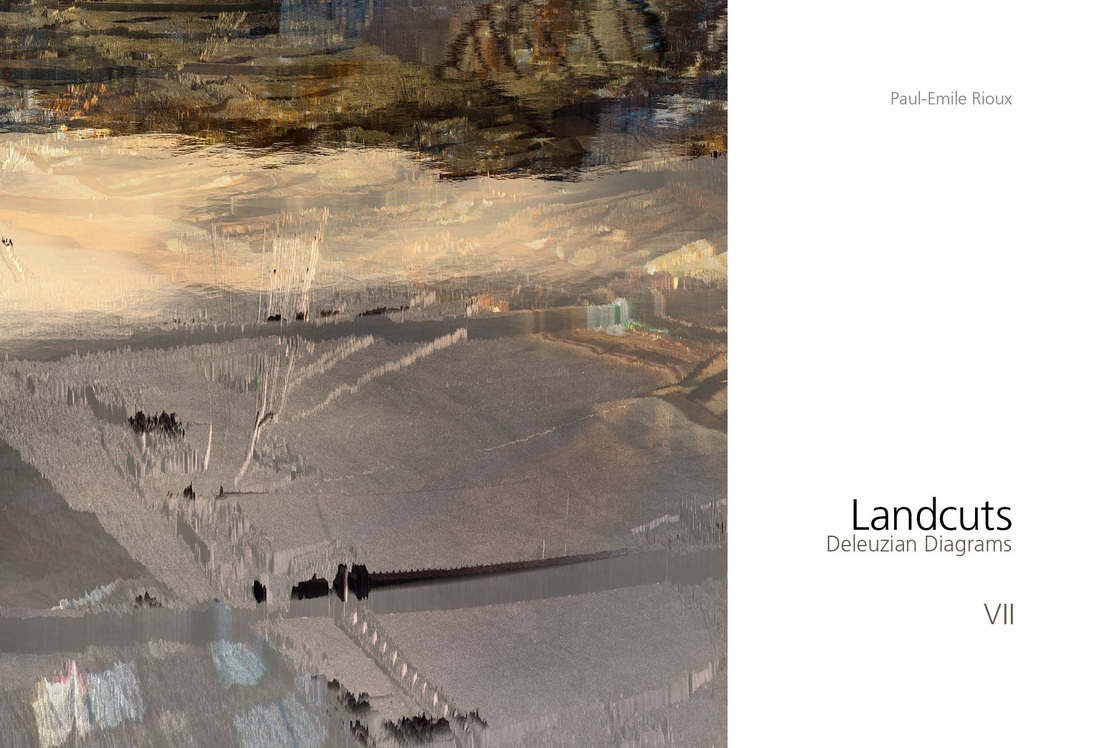

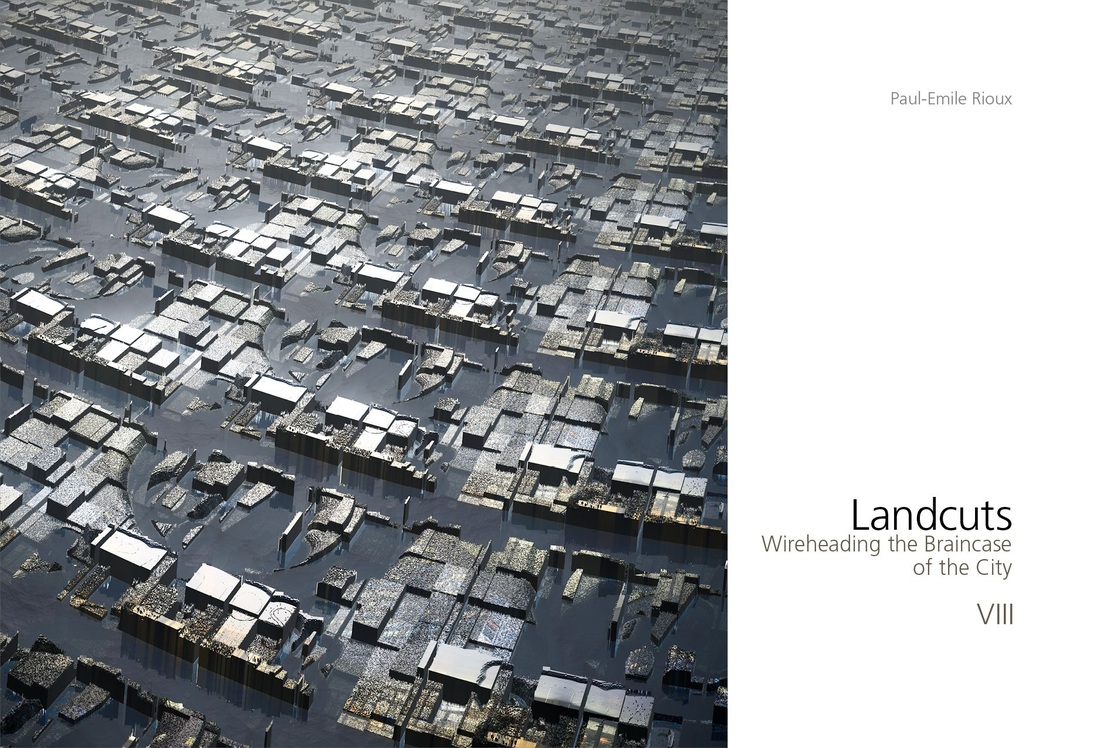

The second and most compelling part of the essay begins with a description of the brain and the neuron in such a way that meaningful comparisons with the computer can be made and inferences drawn. Von Neumann offers a convincing schematic of the digital operation of the neuron: it fires or does not fire contingent upon whether or not it has been adequately activated. Von Neumann was one of the first thinkers to acknowledge the non-linear character of the operation of the brain. He expressed the non-linearity as a combination of digital and analog constructions of the machinery so that the computer metaphor could be better employed. It seems clear Rioux’s artistic methodology is sensible and a serious attempt at replicating the redundant iteration of simplicity upon which the totality of modern computational methodologies are based. In Innards 1 and Innards 2 for example, the artist presents the synapses that empower his inner cities and outlying suburbs.

Von Neumann makes reference to the work of the English logician Alan M. Turing. Turing demonstrated almost a decade earlier that it is possible to develop “short codes.” [37] These short codes, which enable a second machine to imitate the behavior of fully coded machinery, are by analogy, relatable to and revelatory of Rioux’s stratagems—and the guts of his practice. Short codes were created so that one could code more briefly for a machine than its own natural order system would allow, by “treating it as if it were a different machine with a more convenient, fuller order system which would allow simpler, less circumstantial and more straightforward coding.” [38] |

|

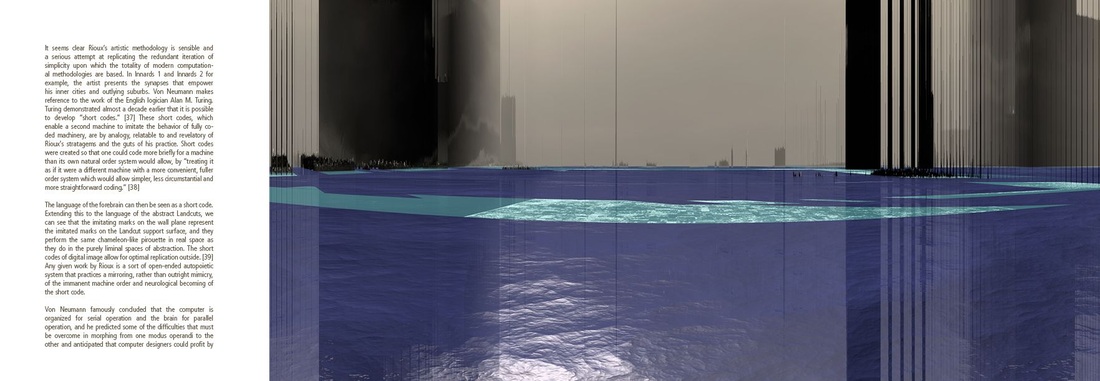

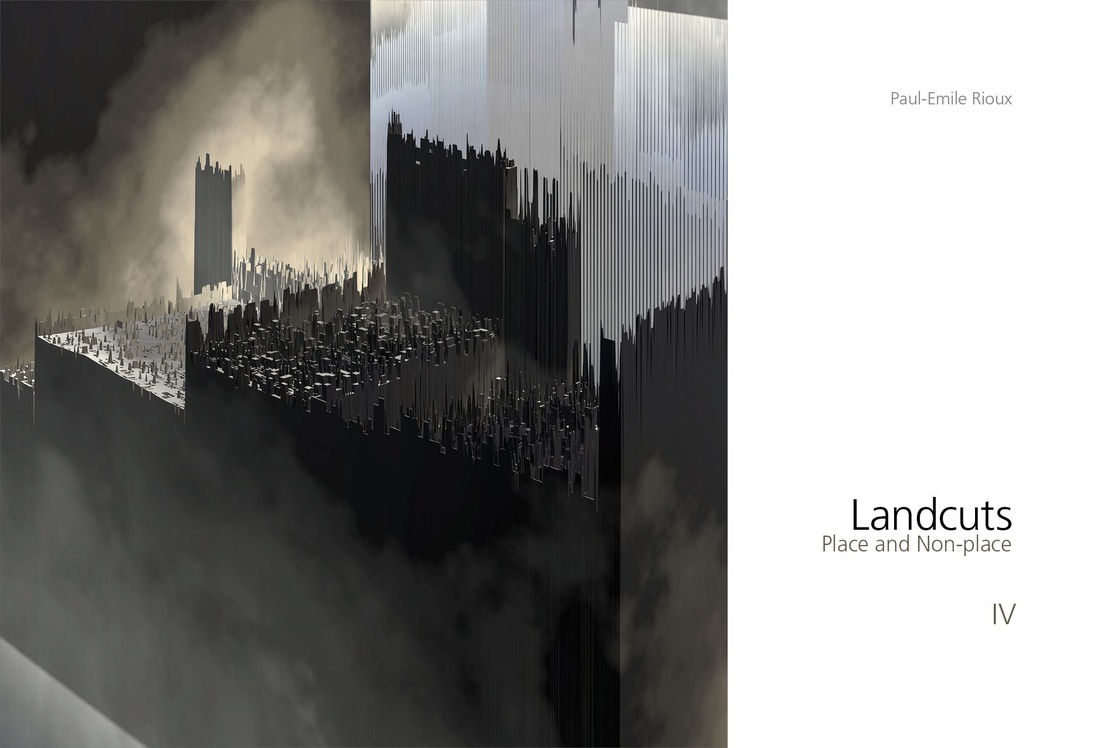

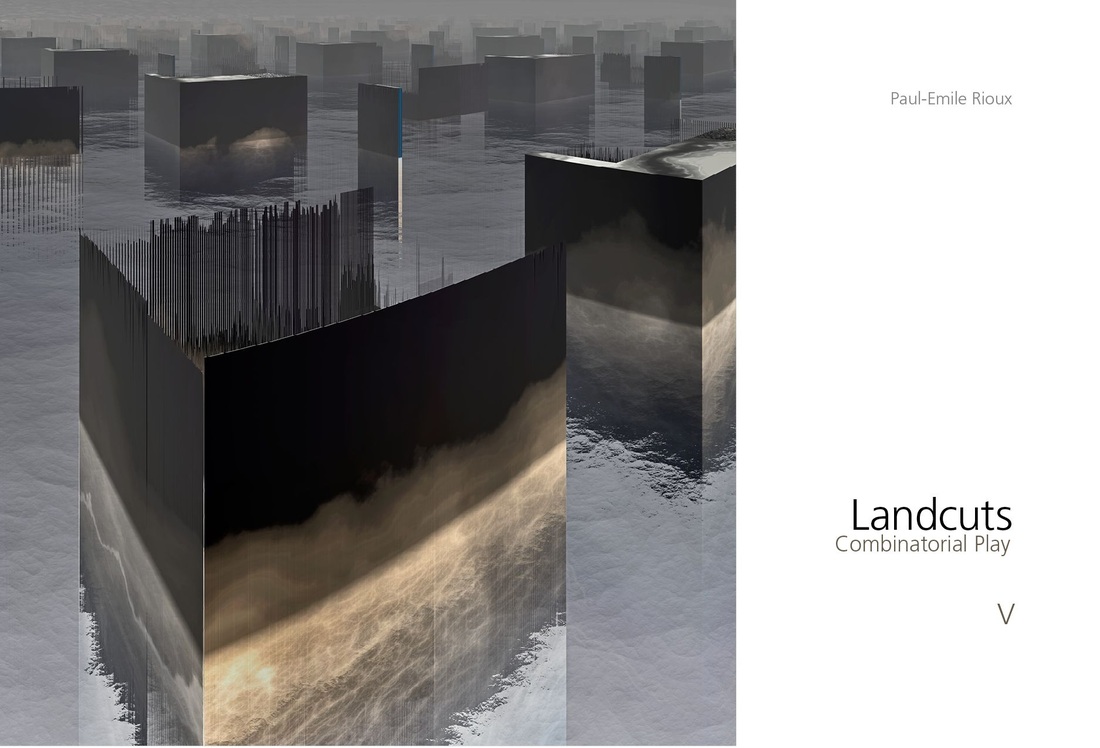

The language of the forebrain can then be seen as a short code. Extending this to the language of the abstract Landcuts, we can see that the imitating marks on the wall plane represent the imitated marks on the Landcut support surface, and they perform the same chameleon-like pirouette in real space as they do in the purely liminal spaces of abstraction. The short codes of digital image allow for optimal replication outside. [39] Any given work by Rioux is a sort of open-ended autopoietic system that practices a mirroring, rather than outright mimicry, of the immanent machine order and neurological becoming of the short code.

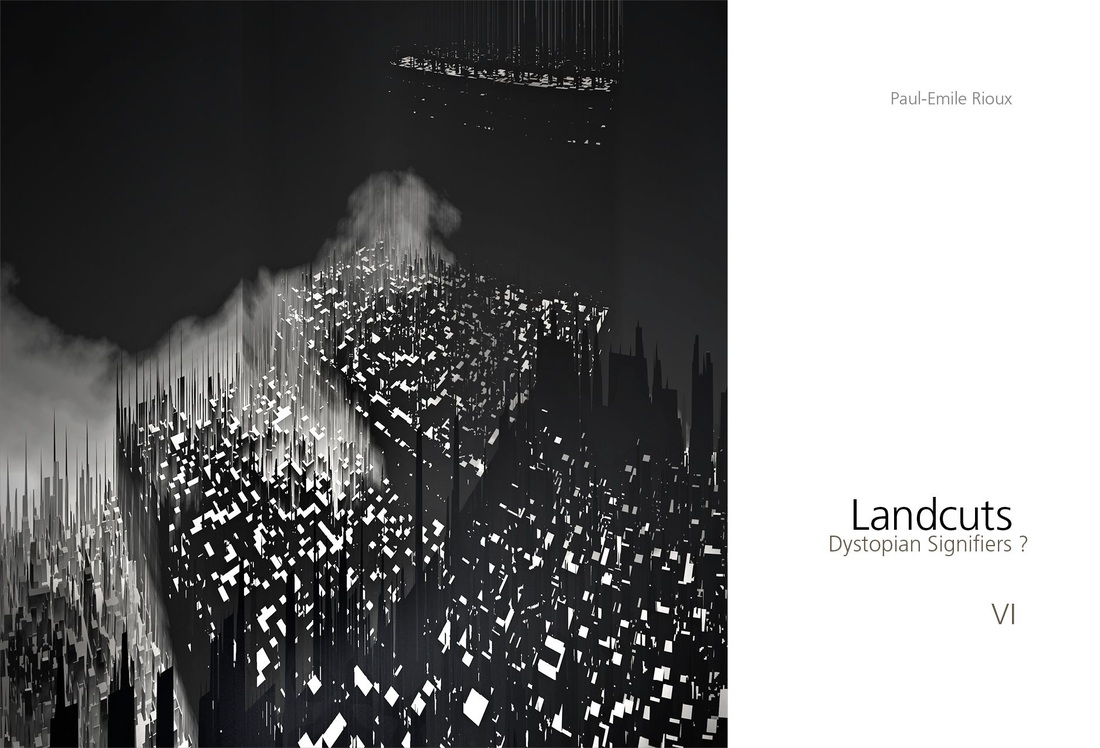

Von Neumann famously concluded that the computer is organized for serial operation and the brain for parallel operation, and he predicted some of the difficulties that must be overcome in morphing from one modus operandi to the other and anticipated that computer designers could profit by modeling features of the human nervous system in their designs. [40] His language is more transparent than opaque, and in building the marvelous scaffolding for comparing computer and brain he reminds us of Rioux’s digital facture and its continuing experiment with exteriority. In works like Untitled (2012), this artist’s tangled skeins of intersecting and overlaid markings result in a wealth of tasty pictorial detail that has a decidedly web-like neuronal counterpart, bringing on an eerie sense of déjà vu for Von Neumann’s brilliant analogue of synapse, axon-dendrite tree, organicity—and computer short codes. Rioux’s trademark monoblock grids relate more readily to neural networks and chromosome mapping procedures. Yet, there is nothing programmatic about these abstractions. They have become more feral and violent as time goes on and radiate a sense of hectic organic growth, of ongoing self-replication, a will to power and expansion. Rioux’s is a healthy, if subversive, invasion/infection of the here and now, no holds barred. He is arguably clairvoyant in his view of integuments in a given cityscape as viral agent, as stealthy pathogen, as warden of both short code and endlessly self-replicating organism. The biological and technological networks enjoy a sort of mutually reciprocal viral invasion, and Rioux’s stratagems are like signaling mechanisms, a new and prophetic means of activating the machine brain. Notes 36.37.38.39.40. John von Neumann, The Computer and the Brain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958). |